From Idea to Reality: Getting to Guaranteed Income

Paul Williams and James Medlock on paternalism, market failures, and welfare policy in the US

By Paul E Williams and James Medlock

June 22, 2021

In a recent piece for Real Clear Policy, conservative scholar Scott Winship presented a case against giving cash benefits to the poor. Winship, the director of poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute, has been making a fuss for several months that giving direct benefits to the poor is bad policy. Despite Winship’s criticisms, Congress and the Biden administration proposed changes to the structure of the Child Tax Credit program—increasing the size of the credit, making it unconditional on income, and allowing it to be paid out monthly rather than in a lump sum at the end of the tax year—which recently became law under the American Rescue Plan.

On the level of policy, these modifications represent small tweaks to the United States’ long-standing tax-credits-as-welfare regime. On the level of experience, they represent families with children receiving a few hundred extra dollars per child to help with basic needs. Especially for very poor families, these changes can significantly impact their material conditions, and in fact the policy is expected to bring a large number of children above the poverty line.

What, then, is the substance of Winship’s arguments against cash benefits? The case boils down to a paternalistic approach to welfare programs—the piece is titled Do People Know What’s Good For Them?—that prioritizes restricted, conditional benefits over the provision of a universal floor for living standards. Winship’s argument is worth examining for what it illuminates about the role of paternalism in safety net policy, and persistent misunderstandings about market choice and market failure that shape welfare policy discourse in the United States.

Neoclassical Paternalism Wants it Both Ways

“Should policy assume that people know what is in their best interest?” Winship asks in the opening of his piece. On its face, this has the appearance of standard-fare conservative paternalism: we simply cannot trust people to make the right decisions, so we must make decisions for them. But the argument here actually cuts deeper, into foundational assumptions of microeconomic theory. The author is quick to admit this: “The bedrock assumption in economics that people generally maximize ‘utility’ in the decisions they make is genuinely useful in modeling choices and illuminating hidden implications. But too many arguments jump to the tautological claim that if someone chooses a certain way, it must have maximized their subjective well-being.”

It is fair to point out that there is a chasm between using the utility framework to understand consumption and investment choices, and the self-fulfilling prophecy of “every choice maximizes utility by virtue of it having been made”—in fact, this same argument is sometimes made by heterodox critics of Marshallian economics. But the utility framework that Winship finds useful for modeling and understanding behavior relies on the assumption that consumers are maximizing their utility. Without that assumption, the outcomes being modeled are no longer “well-behaved.”

Winship wants to have it both ways: he wants to hold onto the usefulness of microeconomic models, but throw out their assumptions when his paternalist ideology gets in the way. Unfortunately, reality is nuanced. And research allows us to understand how people are, or are not, able to increase their welfare. Utility maximization does occur in some places on the market, and in others it simply does not.

If people cannot maximize utility, then the demand levels firms see on the market inaccurately reflect utility maximizing demand. If demand levels are incorrect, then the level of supply firms are providing is incorrect. If supply and demand are off, then prices are, too. If we throw out utility assumptions, Marshallian demand doesn’t hang on by a thread—it just falls down. Instead of making blind ideological claims, we should look to the research to understand what conditions allow people to maximize their welfare, and what conditions hamper that ability.

Imperfect Information Can Hold Back Welfare

While utility maximization can occur in some markets, there are areas where relying on individuals to make choices can leave society worse off. As Kenneth Arrow famously pointed out, the market for healthcare has a number of features that often result in market failure. At the heart of the problem is information asymmetry: health care services and insurance products are incredibly complex, and there is considerable imbalance between patients and providers/insurers. Additionally, demand is generally inelastic—few shop around for a surgery while being rushed to a hospital.

The information asymmetry is so severe that most people are unable to make informed decisions about their health insurance. In a study of health plan choices in the US, a large share of people (including a majority of low income enrollees) chose plans that were guaranteed to leave them worse off financially than an otherwise identical plan. Similarly, in the Dutch health system, choosing plans that leave people worse off in both best and worst case scenarios is extremely common, with only about 5 percent of consumers choosing better than if they had chosen at random.

The market for health services doesn’t fare much better. While rhetoric about “consumer directed health plans” assumed more choice would put pressure on providers to increase quality and lower costs, evidence suggests otherwise. In one study, patients were so unlikely to shop around for healthcare that, on average, someone getting an MRI drives by six lower-cost providers on their way to their appointment.

Given the issues with relying on consumer choice in healthcare, Winship’s critiques of unconditional cash might apply here. In conditions of extreme information asymmetry, our policy should not assume people “know what is in their best interest.” Just because an individual has decided to forgo insurance, or drive past six equal quality, lower-cost MRI clinics, does not mean that they’re maximizing their own welfare.

One solution to these market failures would be to establish a single-payer health insurance program in the United States, which would obviate many of the problems with a consumer choice-based health system. Curiously, Winship and AEI are not supportive of this kind of policy intervention—despite its potential to resolve some of these welfare maximization issues.

Lifting the Poor from Poverty Improves Utility Choices

On the other hand, there are many areas of the market where utility maximization happens quite easily. Developing a policy mix that can solve both these problems requires attention to when markets work and when they fail.

Take the popular paternalistic critique of cash welfare, which centers on the issue of temptation goods, like alcohol and tobacco. Leaving aside normative judgements about whether alcohol and tobacco are good or bad, there are several econometric studies that have looked into the effect of cash transfers on temptation good consumption habits. A 2017 meta-analysis of nineteen previous studies found that cash transfer programs actually decrease recipients’ total spending on temptation goods, with the authors unambiguously concluding that “concerns about the use of cash transfers for alcohol and tobacco are unfounded.” Here, there is clearly no need to condition direct benefits on the kinds of items people purchase with them—people generally know what’s in their best interest.

Another frequent paternalist claim is that, in the case of child benefits, parents can’t or won’t spend the benefit on things that benefit their children. As Winship puts it, “[We] should look for policies that give kids more opportunities, whether their parents know what is best for them but cannot afford it, want to do what is best but don’t know how, or don’t or can’t prioritize their kids. Unconditional cash transfers only help one of those groups.” In this case, the research also disagrees: parents who receive child benefits do, in fact, prioritize the needs of their children.

Canada’s child benefit program is similar to the one recently implemented in the US. A 2015 study looked at how recipients of the benefit spent the money, and found that most households, and in particular lower-income households, increased spending on educational resources like tuition and educational supplies like computers. Recipient households also increased their expenditures on goods like child care, rent and food. A study on the German child benefit reaches similar conclusions. Not only do parents make new purchases they presumably couldn’t have afforded before the benefit, the purchases directly support the welfare of their children. In other words, they are able to maximize their utility when provided the resources to do so.

The Persistence of Paternalism

There are countless studies on the spending habits and outcomes of cash transfers, and the conclusions are nearly unanimous: people know what they need, and the most common limitation holding them back from getting it is poverty. Where there are more pernicious factors holding back welfare gains—like imperfect information in health care markets—socialization can reduce or eliminate many problems.

So why, knowing these things, is it so hard to correct these clear and present flaws? Much of it is political: business interests lobby hard against benefits that reduce the power of the sack, and against health care reforms that would curtail insurer profits. But the unequal distribution of political power does not influence these policy outcomes without support from the public: the lion’s share of the American electorate exhibits rampant paternalism.

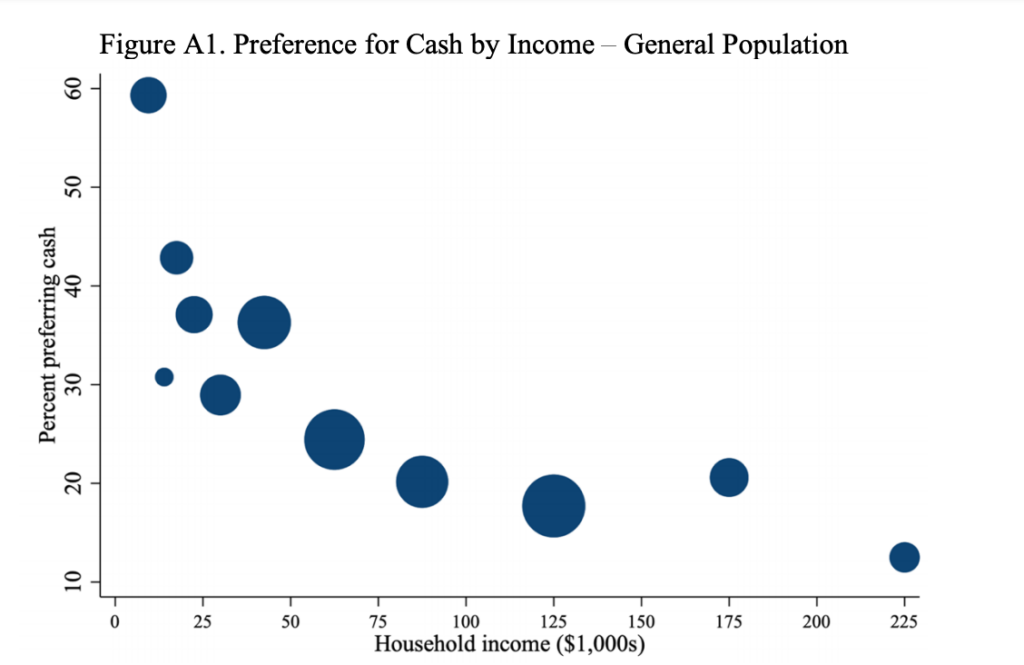

A 2020 study on people’s beliefs with regards to welfare benefits found that the general population overwhelmingly prefers benefits to be distributed in-kind, as many programs in the US such as SNAP and the Housing Choice Voucher currently are. This preference for in-kind benefits, however, fades rapidly as you move down the income ladder: the poorer (and thus more likely to be eligible for such benefits) a respondent was, the more likely they were to prefer cash benefits to in-kind benefits (see figure above).

Specifically, these researchers conclude that “[g]eneral population preferences are strongly correlated with beliefs about how the poor spend their money.” Some of the most common words used by opponents of cash benefits to justify their preferences were “drug”, “alcohol”, “frivolous,” “cigarette,” and “waste.” But they also find evidence that “preferences and the underlying paternalism can be changed with economic reasoning about the value of choice.”

While there is evidence that individuals’ attitudes can change on this issue, more research is needed to understand what factors drive the persistent belief—shared by Winship and millions of Americans—that the poor don’t know what’s best for themselves. (In the policymaking world, there is also evidence that support for paternalistic policies is not just borne out of ignorance of the economic benefits of cash benefits, but can come from industry groups jockeying to increase their market shares through voucherized programs.)

An applied research program is needed to explore messaging strategies for guaranteed income that can combat these paternalistic biases and move the welfare discourse forward. But for Winship, who is willing to yank down the foundations of economic thought just to hold on to repeatedly debunked beliefs, there may be very little hope.