From Idea to Reality: Getting to Guaranteed Income

Robust evidence for $1400 relief and recovery checks

Download as PDF here.

Claudia Sahm, Senior Fellow

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and widespread economic hardship, a debate is taking place over who should get a $1,400 check and the overall size of the $1.9 trillion Biden relief package, known as the American Rescue Plan. To lower the price tag, Republicans want to lower the income cutoff for a $1,400 check from $75,000 per adult—as was the case in the CARES Act and the December package—to $50,000 per adult.

Lowering the income threshold would mean that 71% of households would get a $1,400 check, down from 84% who got a $600 check, according to Kyle Pomerleau at the American Enterprise Institute. That is about 50 million people who would not see their relief topped up to $2,000, as Democratic leadership in Congress and President Biden promised if the Democrats won the Georgia special elections, which they did. This brief provides extensive evidence on how the checks benefit people and help spur an economic recovery for all. Drawing on over a decade of rigorous research, I argue that checks should be in the next relief package and that everyone who received a $600 check should receive a $1,400 check.

Executive Summary

The debate over cash relief in the form of $1,400 checks is about who needs more money and who will spend it. Many of the disagreements hinge on whether the priority now should be relief or stimulus. Some argue that the checks—which go to all but the highest-income households—are poorly targeted and many who will receive a check do not need it. Others worry that people will largely save their checks initially and will only be spent much later when demand is stronger and thus risk overheating of the economy.

A recent study by Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Michael Stepner at Opportunity Insights, using less than a month of spending data, argues, “targeting the next round of stimulus payments toward lower-income households [making under $78,000] would save substantial resources.” Their advice to target the checks more narrowly coincided with a live discussion among policymakers about whether the income cutoff should be lowered from $75,000 per adult, as in prior checks in 2002, to $50,000.

Chetty et al.’s findings, though widely circulated, are preliminary and at odds with many peer-reviewed studies over the past decade on how families use their stimulus checks. Moreover, unlike those prior studies, the methods and underlying data that Chetty et al. use have not been vetted. There appear to be flaws in their approach and a wider margin of statistical error than their policy advice implies. My critique of the new Chetty et al. study is based on my prior research, as well as more than a decade studying the effects of fiscal policy at the Federal Reserve and the Council of Economic Advisors.

In this brief, I argue—contrary to Chetty et al.—that the $1,400 checks should go to everyone who received a $600 check. Further targeting of the checks by income would miss millions of people currently in need of the extra money and slow our progress toward economic recovery for all.

These facts support near-universal checks in the next stimulus package:

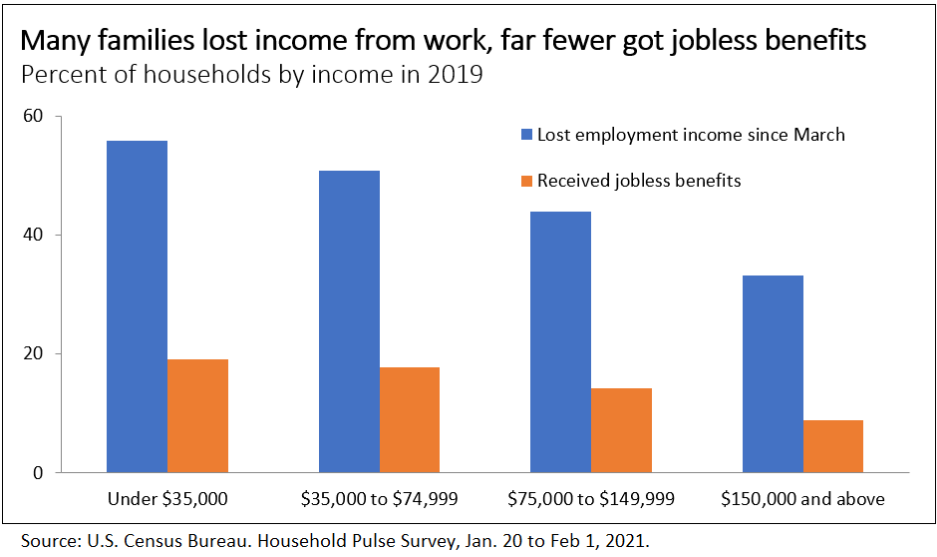

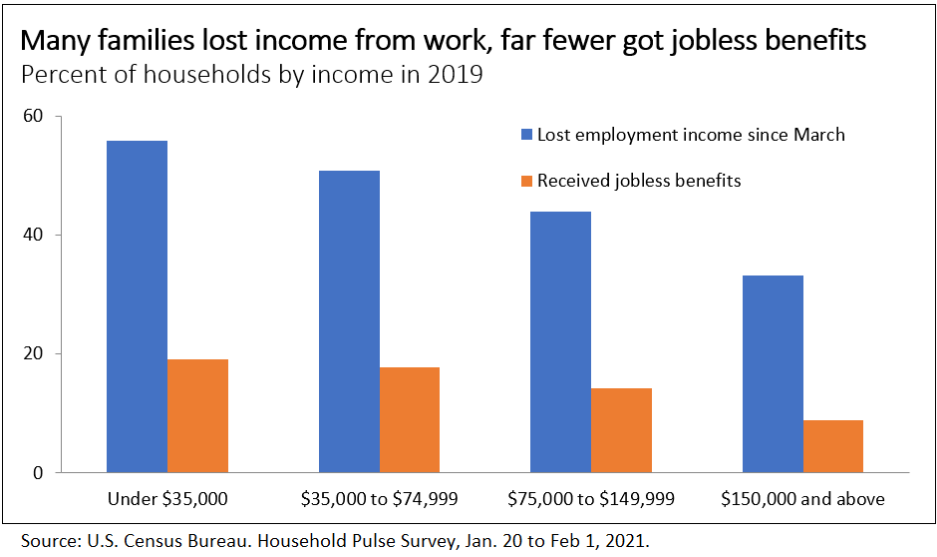

- Half of U.S. households lost income from work last year, but less than one fifth received jobless benefits. The unemployment insurance system, despite being targeted to those hardest hit, is missing millions whose income declined since the crisis began. The checks help fill that gap.

- Even among many wealthier families, the loss of income can cause financial strains and increase the amount of stimulus checks that families would spend, according to research on household liquidity and savings.

- The government lacks information to target checks to people hardest hit in 2020-21 or those most likely to spend. Available data are insufficient to identify all those falling through the cracks in our safety net due to the pandemic and job loss.

- The checks are already designed to target lower-income households. The top 10% by income never received checks, and the next 10% only a partial one. Further limiting eligibility would lead to millions fewer receiving the $1,400 check than the $600. Many need the money.

The analysis below explains my case for checks, and what the research says about how households with different income levels use cash relief. I conclude with guiding principles for evidence-based policy.

What households need a relief check?

Although nearly half of U.S. households lost income in 2020, many fewer received jobless benefits. This means that jobless benefits targeting the unemployed did not reach all families who lost income from work during the crisis. While the gaps were largest among the lowest income families, many families above the Chetty et al. cutoff of $78,000 in income were affected, too.

Economic hardship shows up in other ways too. At the end of last year, 12 million families were $6,000 behind on their rent, mortgage payments, or utilities on average. Food banks across the country have been overwhelmed during the crisis and food insecurity is on the rise. The relief to families and the unemployed in the CARES Act last year was a lifeline and that allowed many families to build a small cushion. A Federal Reserve survey in July 2020 found that 70% of families said they would use cash or its equivalent to pay an unexpected $400 expense—up from 63% before the pandemic. The improvements in economic security were largest among low- and moderate-income families, especially among those receiving jobless benefits. The money from Congress, while it lasted, served many needs of families, not only spending. Researchers at the JPMorgan Chase Institute showed that both spending and savings rose after CARES Act relief began, then fell back after many programs ended this summer. The earlier relief efforts worked but hardship remains, so President Biden’s proposed $1,400 checks and other provisions, especially for the unemployed, are urgently needed. The ongoing crisis demands the $1.9 trillion price tag.

Lower income thresholds, as Chetty et al. and some other analysts promote, would create more gaps in coverage. For example, some regions where COVID-19 caused the most hardship would lose out from a lower income cutoff due to their higher costs of living. For example, New York City, the metro area with the highest number of COVID-19 cases and far more racially diverse city than the rest of the country, has a median family income of $83,000. Likewise, in Kahului, Hawaii, an area with double-digit unemployment due to reliance on tourism, the median income of $81,000 is above the lower income threshold for checks. It is imperative that policy attends to such unequal treatment of families, not one politically expedient study.

How will relief checks be spent?

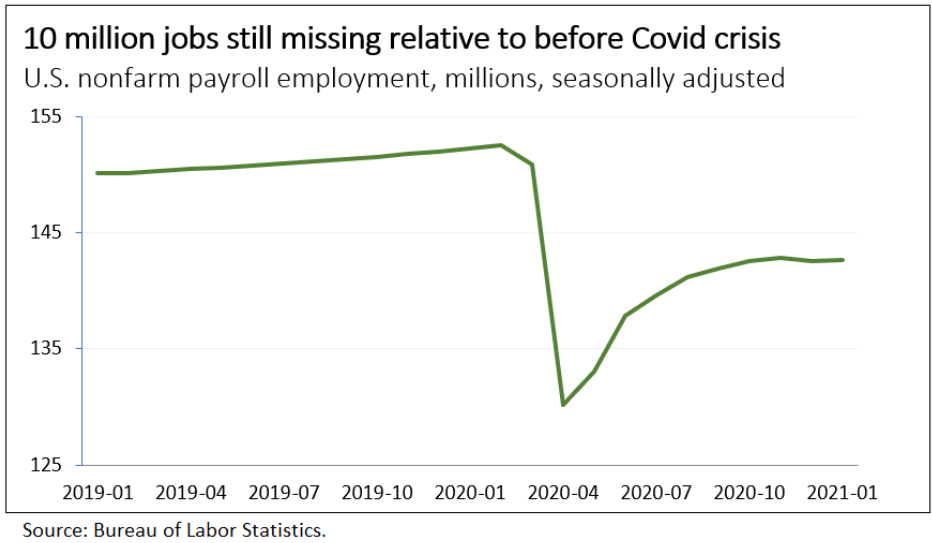

In addition to mitigating hardship among families, as discussed above, the checks, totalling over $400 billion, will speed an economic recovery for all. Currently, the United States has 10 million fewer jobs than before Covid. That shortfall is larger than anytime in the Great Recession. After the CARES Act with the $1,200 checks began we gained back nearly 10 million jobs. Another large relief package and widespread vaccinations are necessary to close the remaining shortfall.

Over a decade of research tells us that one half to two thirds of total dollars in stimulus checks are normally spent within a few months, including the 2020 CARES checks. Families with low and high income spend their checks. More targeting by income, which would reduce the aggregate dollars of the program, would dampen the much-needed boost to the economy.

Stimulus checks, along with other relief to families create a positive, self-reinforcing dynamic in the economy. A family who receives a check spends it, then a business owner makes more money and can bring back laid-off employees. Those re-employed workers will spend more money and so on. This chain reaction is referred to as the “fiscal multiplier.” The more money to families the stronger the tailwind for the recovery will be.

The new analysis by Chetty, Friedman, and Stepner estimates suggest that higher income families will not spend their checks and thus will not contribute to the economic recovery. To make their case, they estimate how much families have spent so far out of the $600 checks. Specifically, they find that:

“Households earning more than $78,000 will spend only $105 of the $1,400 stimulus check they receive…targeting the next round of stimulus payments toward lower-income households would save substantial resources that could be used to support other programs, with minimal impact on economic activity.”

Such a strong conclusion requires strong evidence. In my expert opinion, their study does not meet that standard. Thus, the attention their preliminary findings have received in the current policy debate over the $1,400 checks is problematic. One new, unvetted study should not drive policy, especially when it is at odds with over a decade of peer-reviewed research. Evidence-based policy requires that we critically evaluate findings and compare them to prior research.

Chetty et al. have shared only limited information about their analysis which makes external assessment difficult; nevertheless, I see several red flags in the materials that I could review. The initial news coverage was based on the one-pager they posted. A week later, they posted an appendix to their new analysis, which refers to the appendix of another unvetted paper. Their methods in the new analysis of the checks, as well as the unvetted, underlying data-set (The Opportunity Insights: Economic Tracker) were constructed last spring and have been used in other studies, but have several problems. These shortcomings should disqualify this new study and prior analysis with the tracker from informing the current policy debates about the relief package.

The biggest red flag I see is their data. They argue higher-income households should not get the $1,400 check, because they did not spend their $600 check, despite the fact that they do not have data on household-level income or spending. Instead, they use median family income data from 2014 to 2018 at a zip-code level from the Census Bureau as a proxy for household income. In a single regression, they compare zip-code-level income with county-level credit and debit card spending. The data with debit and credit transactions are from Affinity Solutions, a private company. The underlying data set required substantial adjustments by Opportunity Insights, and cannot be reviewed by outsiders. Moreover, unlike official surveys, their data are not representative U.S. households. Despite my years of experience building a new spending series with private company data for the Federal Reserve, it is near impossible for me to evaluate the quality of their spending series. The methods I see described in their appendixes do not inspire confidence.

In contrast to their spending data, I can assess the problems in how they use the income data, since those underlying, nationally representative data come from an official statistical agency. The Census Bureau publishes thorough documentation on their statistical methods and its limitations. They clearly state that official estimates at finer geographies, like zip codes or counties, are measured with error. Users of the data should acknowledge that uncertainty in any analysis with data. Chetty et al. do not discuss any statistical uncertainty in their data or their regression. Instead they give a sharp income cutoff of $78,000 in their policy advice. My recent piece discusses in more depth some of my concerns with their methodology.

My critical evaluation of the Chetty et al. analysis is grounded in my expertise on how families use their stimulus checks, I worked over a decade at the Federal Reserve estimating the macroeconomic effects of fiscal support to families during the Great Recession and its recovery for policymakers. I have also done research on the 2008 stimulus checks, the 2009-10 Making Work Pay tax credit, and the 2011-12 payroll tax cut, and most recently, the $1200 CARES Act checks with economists Matthew Shapiro and Joel Slemrod at the University of Michigan. In 2019, I applied my expertise to create a well-received policy proposal for automatic checks during recessions. I developed a recession indicator, now known as “the Sahm Rule,” to start the checks and other automatic stabilizers as soon as we enter a downturn. In my policy chapter, I also discuss findings on the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) out of the 2001 and 2008 checks (Sahm 2019, page 72-74). Last year with Mike Garvey, I summarized preliminary research findings on the CARES Act checks in (Garvey and Sahm 2020). See the Appendix of this policy brief for my expert assessment of findings on the spending of relief checks by income.

In short, the peer-reviewed decades of research show that families spend a substantial fraction of their stimulus checks quickly. Findings on different propensities to spend by family income are mixed and imprecisely estimated. There is too much uncertainty to claim that higher income families spend less of their checks. Yes, research also shows that some of the checks are used to increase savings or to pay off debt. These other uses are relief to families, even if they do not quickly stimulate aggregate demand.

The result by Chetty et al. that higher income families do not spend any of their checks is at odds with over a decade of research. Their result is an outlier and they do not report the statistical uncertainty surrounding their estimates.

While income is not a reliable predictor of spending, several studies find people with low bank account balances are most likely to spend. These families, with low savings, are arguably some of the ones in most need of check in this crisis and other recessions. But the federal government does not know what is in anyone’s bank account. Income, particularly measured by 2019 tax returns, is not a good enough proxy to cut out 50 million people from $1,400 checks. Some of these families, even though they have higher incomes than others who will still get the check, need the extra money. The prospective budget savings from more targeting by income is relatively small (roughly $35 billion), but the likelihood of missing people in need is large.

In the current debate, if policymakers decided that a $1.9 trillion relief package was too large to pass, and had to find ways to reduce the cost, a fair conclusion may be to limit checks for those with the highest income. However, this conclusion is not supported by evidence that higher-income households have, in fact, not lost income, are not in financial hardship, or are not likely to spend these checks. The Chetty et al. analysis does not justify for more targeting.

Critical lessons for evidence-based policy

The debate over stimulus checks and the overall relief package is ongoing. Numerous factors are at play and the final decisions are in the hands of elected officials in Congress and the White House. From the perspective of economic expertise, it is deeply disconcerting to see a poorly-done study that is at odds with decades of research being used to justify a politically-expedient outcome.

Economic experts and policymakers alike can draw lessons from this experience and set stronger norms for how to use research responsibly in policy deliberations. First, researchers should recognize that our findings add information. They do not drive policy. Sometimes our findings are not feasible to implement and sometimes they are not politically smart. Before making recommendations, the findings need to be vetted by external experts, set within the context of other studies, and explained transparently to the public. In economic policy, being right is what matters.

Over a decade working as an economic policy expert, I have learned many lessons at government agencies and think tanks, as well as from officials at the Federal Reserve, Congress, and the White House. Here are three guidelines we must follow:

- Engage in a robust debate and analysis, weighing the best evidence from a wide range of scholars using various methods.

- Understand the diverse lives of people across the country, their hardships, and their opportunities. Then use that understanding to inform our policies and research methods.

- Include a diverse group of advisers, scholars, and decision-makers in policy deliberations.

We are falling short on all three. Following these guidelines will improve our economic policies and better serve the millions of people our policies affect. Strengthening our norms is as hard as it is essential. Policies grounded in evidence and empathy are better policies. We need decision makers and policy advisers who have open minds and are held accountable for their actions.

Appendix: Research on spending out of checks by family income

Peer-Reviewed, Published Research on 2008 Stimulus Checks

- Parker, Souleles, Johnson, McClelland. (2013). “Consumer Spending and the Economic Stimulus Payments of 2008.” American Economic Review. They find that within 3 months after receipt the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) out of the 2008 checks is 1.3 for families with less than $32,000 in income versus 0.7 for families with income over $75,000. These estimates by income (with large standard errors) are not statistically different from each other. They use the Consumer Expenditure Survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The survey is representative of the U.S. population and is widely used.

- Sahm, Shapiro, Slemrod. (2012). “Check in the Mail or More in the Paycheck: Does the Effectiveness of Fiscal Stimulus Depend on How It Is Delivered?” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. They find that 23% of families with income under $35,000 said they “mostly spent” their 2008 check over the prior year versus 19% of families with income above $75,000. These estimates by income are not statistically different. They use the Survey of Consumers at the University of Michigan which is used widely in research and economic analysis and is representative of the U.S. population. Note, the implied MPCs are larger than the “mostly spend” percentages because some who say mostly spend or save will spend some. See Parker and Souleles (2019) for the translation to MPCs.

- Broda and Parker (2014). “The Economic Stimulus Payments of 2008 and the Aggregate Demand for Consumption” Journal of Monetary Economics. They find that families with income under $35,000 spend less $69 out of their checks within 10 weeks on groceries, electronics, and small appliances versus $92 among families with income above $70,000. In the initial 4 weeks, low-income families spend somewhat more than high-income families, but the pattern reverses by ten weeks. However, none of the differences by income are statistically different. Moreover, this study covers only a fraction of household spending. They use the Nielsen Consumer Panel, which is an opt-in private company data set of goods with bar codes that consumers scan in for Nielsen after their shopping trips. The data are not representative of the population.

Preliminary, Unpublished Research on 2020 CARES Act Stimulus Checks

- Sahm, Shapiro, Slemrod (2020). “Consumer Response to the Coronavirus Stimulus Programs.” As in their study of the 2008 stimulus checks, they find basically no differences in spending by family income. Specifically, 13% of families with less than $35,000 in income in 2019 said they expect to “mostly spend” their checks over the coming year versus 17% of families with income over $75,000. These estimates are not statistically different from each other. As noted above, MPCs are higher than the “mostly spend” percentages, and spending out of rebates rises over time. The spending out of the 2020 CARES checks is similar to the 2008 checks. Again, they use the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers, which is representative of the U.S. population.

- Natalie Cox, Peter Ganong, Pascal Noel, Joseph Vavra, Arlene Wong, Diana Farrell, and Fiona Greig. (2020). “Initial Impacts of the Pandemic on Consumer Behavior: Evidence from Linked Income, Spending, and Savings Data.” They find that the level of spending rises sharply for families with income less than $63,000 as soon as the checks begin to arrive. The spending of families with income above $63,000 increases more slowly. Note, some of these higher-income families did not receive checks. They do not report an MPC by income or the statistical precision of their estimates for the level of spending by income. They use data from bank accounts from a sample of JPMorgan Chase customers. The data cover moderate to upper-middle income families well, but exclude the unbanked families, as well as high-net worth families. As a result, they are not representative of the U.S. population. Unlike other private big data sources in this summary, JPMorgan Chase Institute developed their data over the past six years, and researchers have used them in peer-reviewed, published studies.

- Baker, Farrokhnia, Meyer, Pagel, and Yannelis. (2020). “Income, Liquidity, and the Consumption Response to the 2020 Economic Stimulus Payments.” They find that households with less than $24,000 in annual income have an MPC of 0.57 out of the checks within three weeks versus an MPC of 0.33 for families with over $24,000. These differences are statistically different, but the income cut offs are much lower than in other studies. They use data from SaverLife, an Fintech app that encourages people to save. Their data are not representative of the U.S. population and are likely biased toward people who will save, not spend their checks.

- Ezra Karger and Aastha Rajan (2020). “Heterogeneity in the Marginal Propensity to Consume: Evidence from COVID-19 Stimulus Payments.” They find that families with less than $1,000 in savings (three-month difference between spending and income on debit and payroll cards) have an MPC of 0.62 in two weeks of receipt and versus an MPC of 0.40 for families with $5,000 in savings. These differences by savings level are statistically different. They do not present results by income. They use data from Facteus, a private company that provides spending transactions using debit and payroll cards. The data are not representative of the U.S. population.

About the author:

Claudia Sahm is a macroeconomist and economic policy expert, and a Senior Fellow at JFI. In 2019, she proposed automatic, repeated stimulus checks to families in recessions. Her proposal was part of the Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy. For that work, she created a reliable recession indicator, now known as the “Sahm Rule.” The rule, which is based on changes in the national unemployment rate, would be used to automatically start fiscal relief like stimulus checks as soon as a recession begins. She founded and currently runs Stay-At-Home Macro consulting and regularly contributes at The New York Times and Bloomberg Opinion.

Most recently, she was the Director of Macroeconomic Policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Previously, Sahm was a section chief in the Division of Consumer and Community Affairs at the Federal Reserve Board, where she oversaw the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking. Before that, she worked for 10 years in the Division of Research and Statistics on the staff’s macroeconomic forecast. She was a senior economist at the Council of Economic Advisers in 2015–2016. Sahm holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Michigan (2007) and a B.A. in economics, political science, and German from Denison University (1998).

About the Jain Family Institute:

The Jain Family Institute (JFI) is a nonpartisan applied research organization in the social sciences that works to bring research and policy from conception in theory to implementation in society. Within JFI’s core policy area of guaranteed income, JFI consulted on the Stockton, CA SEED pilot, the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend, and related policies in New York City and Chicago, as well as a forthcoming pilot launching in Newark. JFI has also provided expert commentary on a range of cash transfer policies from relief checks to the EITC and CTC. JFI is leading an evaluation of a 42,000-person guaranteed income program in Marica, Brazil, a keystone of the movement for a solidarity economy. Founded in 2014 by Robert Jain, JFI focuses on building evidence around the most pressing social problems. The Phenomenal World is JFI’s independent publication of theory and commentary on the social sciences.

Contact us here.