Millennial Student Debt

Cost Deception at Elite Private Colleges

By Laura Beamer, Lead Researcher in Higher Education Finance, and Eduard Nilaj, Data Science Research Associate

Download the full PDF here for the best reading experience.

Find our series of reports on Millennial Student Debt here.

American colleges and universities, especially private ones, award institutional scholarships in order to compete for prospective students. A new class action lawsuit alleges that colleges are conferring the most generous aid packages to the wealthiest applicants to the disadvantage of the neediest students whom the aid would have gone to otherwise. The endgame is that these wealthy students have families with hefty bank accounts that those institutions could tap into. The lawsuit has renewed interest in how elite colleges calculate financial aid packages and the many ways the system is rigged against the neediest students, especially through unanticipated debt accrual.

Two widespread deceptive pricing practices in the higher education system are front-loading and cost underestimation, as we covered in our 2021 report, “How Schools Lie (1).” Front-loading is the process by which first-time students are awarded significantly more free financial aid than latter years of college (2). Cost underestimation is when colleges mislead students on non-direct costs of attendance, like cost-of-living, thereby presenting them with artificially low estimates (3). Front-loading and cost underestimation are used to entice first-time students to enroll in a particular institution under the guise of affordability. Unsurprisingly, leading (4) colleges and universities are utilizing these competitive and predatory tactics as well.

It is a clever ruse because data on institutional aid packages does not exist at the aggregate level. Likewise, processes for calculating financial aid packages are not made public, and when students eventually surpass their expected budget, institutions can rely on the federal student loan program to fill any funding gaps— except that even when a student borrows the maximum federal loan amount, because of cost underestimation and the failure of colleges to include all pertinent expenses in costs of living estimations, students still cannot make ends meet. The findings tell a familiar story: while colleges across the higher education system are utilizing these deceptive practices, the most underprivileged students are the most negatively impacted, causing them to fall further into debt, or even drop-out or transfer in the process.

Not long after “How Schools Lie” was released, there was external interest in determining if our country’s most prestigious colleges and universities were participating in this deception. In terms of front-loading and cost underestimation, the answer is yes; as expected, the practice is more prevalent at private institutions. Furthermore, to test the pervasive assumption, held even by President Biden, that students at elite colleges either do not borrow or are privileged enough to repay their student loans, we analyzed indebtedness and loan repayment at these leading institutions. Analysis shows that borrowers at these schools are suffering from the same worrisome student debt trends as the rest of the country—larger balances, lengthening repayment terms, and generational indebtedness.

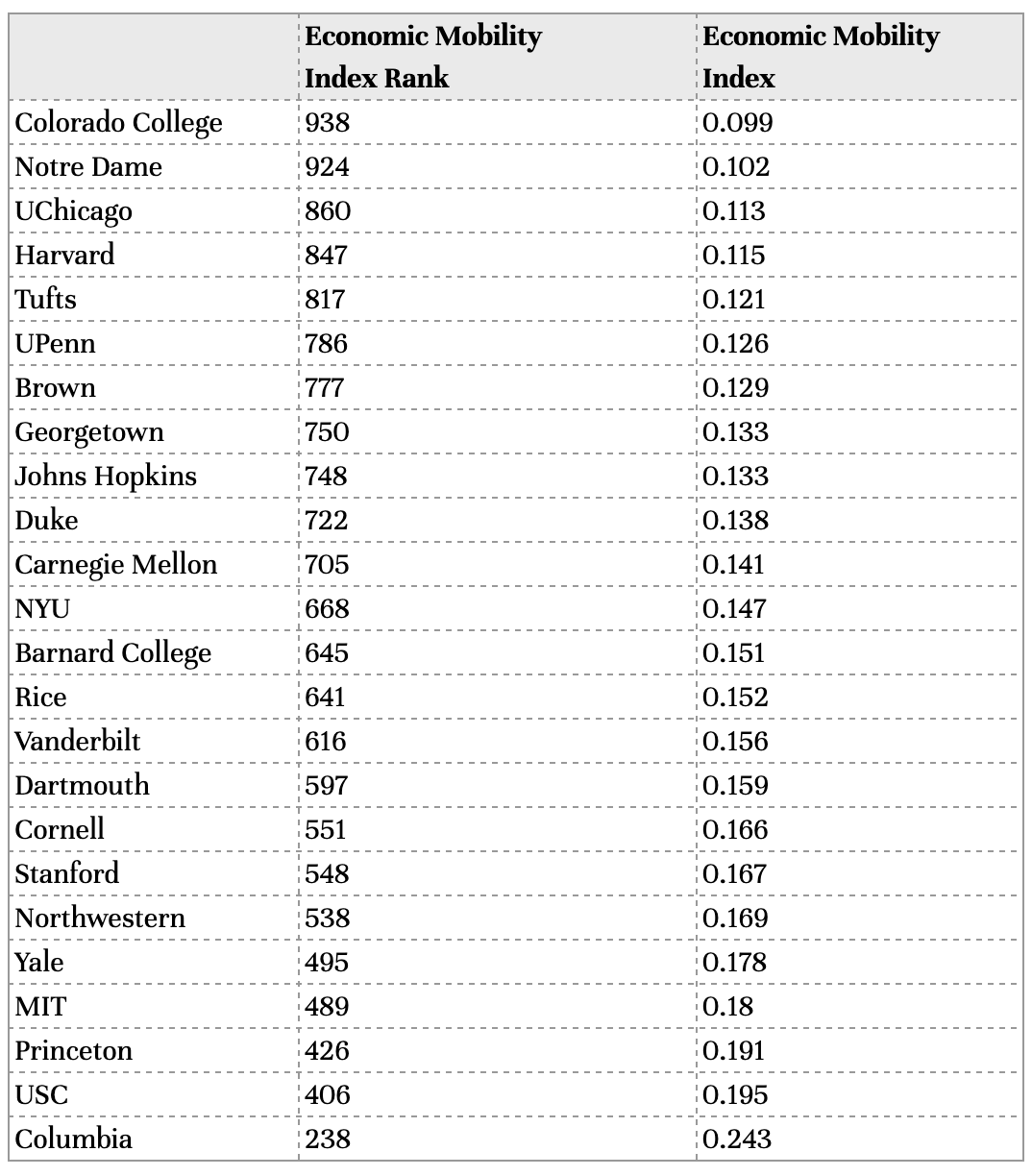

The presence of these trends inspire us to rethink institutional rankings, especially given that popular ranking mechanisms fail to credit the colleges that uplift Pell grantees. When utilizing an alternative rankings metric that measures colleges against economic mobility, our list of leading private institutions fails to attain high rank—in fact, the best placement is Columbia University at 238th place, in stark contrast to Columbia’s 2nd place rank in the U.S. News’ 2022 Best National University Rankings.

This research counters long-held assumptions about college affordability and shows that there are no exceptions or asterisks when it comes to the student debt crisis. Moreover, it begs us to question the extent to which financialization has seeped into all aspects of higher education, not just the for-profit sector. Elite institutions are just as capable of cost deception—in fact, their prestigious status and undeserving rank shields them against detection.

Indebtedness and Repayment

The College Scorecard data on student loan debt for completers and non-completers at these institutions gives reason to be concerned. Moreover, the data belies the myth that undergraduates at these institutions mostly attend expense-free and therefore do not need to borrow for college. The lack of disaggregated, individual-level data makes it difficult to discern the full impact deceptive cost tactics have on discontinuation and student debt accrual, but aggregate data indicates its troublesome effects, and that Pell grantees are disproportionately impacted. Especially for students who withdraw from college with debt but without a credential, their uphill battle entails worse repayment rates and higher likelihood of forbearance and default.

A similar false assumption is applied to parent borrowers of undergraduate dependents at these colleges—that those that do borrow on behalf of their dependents are predominantly doing it to ensure the students do not have to borrow on their own. In line with other research, we find that Parent PLUS borrowers at elite institutions will usually have higher origination balances if their dependent is also borrowing on their own behalf.

Student loan burdens in absolute value are worrisome on their own account, but minimizers argue that the debt pays off through an earnings premium on the new credential: the ex-ante financial security due to attending college is worth student debt accrual and a reasonable number of repayment years. As data on repayment has become more readily available, it has become abundantly clear how far-fetched that claim is. The false promise of credentialization leads millions of students and their families into indebtedness that is more and more often not being repaid due to stagnant wages, spurious degrees, insurmountable payments due, or the combination thereof.

Low repayment rates across higher education can be partly attributed to federal income-driven repayment (IDR) programs, whereby a borrower’s payment due is a set percentage of their adjusted gross income—an amount less than the amortized amount due under the original loan contract. The government created this program under the assumption that borrowers straight out of college would eventually meet an earnings potential that would afford the original contract’s amortization schedule. Research on IDR and the crisis of non-repayment contrasts with that prediction, showing that repayment terms are lengthening on average due to unrealized earnings and interest accrual.

The natural inclination at this point is for minimizers to claim that non-repayment is a function of the particular program or degree and how valuable it is in the labor market—that borrowers made a poor choice about when and where to go to college and what to study. Nothing disproves that logic like displaying student loan repayment rates at private elite universities where, even with premier social and professional networks and stellar credentials, borrowing cohorts are experiencing repayment timelines of well over ten years. While these institutions’ repayment rates are better than industry averages, they represent a heavy burden for students, especially given the preeminent rankings of these schools.

The disheartening repayment rates in the above graph pertain only to direct federal student loans and, presumably, would be much worse if Perkins or institutionally-sponsored loans could be included in the calculation. Virtually no data is available on repayment for these types of loans except what investigators have managed to extract from legal proceedings—they do not paint a sunny picture.

Front-loading and Cost Underestimation

Of the most selective private colleges, the disparity between average free aid for first-year students and all other undergraduates was the highest at Columbia University—a three year average difference of $14,128 (USD 2019). The median additional aid front-loaded at the top colleges in this brief’s analysis was $4,015 at private institutions compared to $981 at public institutions (5). The differences in average free grant aid between the student groups at public colleges are most likely attributable to decreased merit-based state aid, whereas at private colleges, the difference is most likely attributable to decreased institutionally-funded aid in later years of attendance. At some of these colleges, a selection effect may also be at play: the students with the least flexibility to adapt to unexpected costs may discontinue in later years, and their omission from free aid statistics in those years leads to lower average aid across the cohort. Gaps in data availability make it difficult to discern the source of the front-loaded aid, and impossible to examine trends in college continuation or the impacts of student loan indebtedness. Nonetheless, the shock of losing thousands of dollars in free aid year-over-year would certainly be a useful determinant in an applicant’s college choice; of course, that data point is never included on financial award letters to first-time students.

It’s evident that private universities utilize cost underestimation far more than their public peers—and more egregiously. The median difference in off-campus ancillary cost underestimation at the top colleges in this study was $2,899 at private institutions and $1,367 at public institutions. If the Department of Education simply calculated these costs on behalf of colleges, as Veterans Affairs does, it would work to both demystify college financial aid letters and benefit the budgetary expectations for millions of students and families. Columbia University is the only private institution in our list that did not underestimate off-campus ancillary costs.

The discrepancy between real world costs and the college estimates that students rely on may impact both college completion and student debt accrual. Lower retention and graduation rates of first-time full-time students may be the result of unanticipated prohibitive costs. A median of 73 percent of first-time full-time students have graduated eight years after matriculating at the selective public colleges in this study; that figure is 95 percent at the selective private colleges.

Notice that most of the Ivy League colleges are omitted from the off-campus ancillary costs chart. This is because many of them do not allow undergraduate students to live off-campus. Because of this, the data point is not reported to the Department of Education even though these colleges may still be underestimating off-campus costs for graduate students, for whom cost data reporting is scant.

Rank and Status

The previous analysis on cost underestimation and indebtedness calls into question how institutions are ranked by their self-aggrandized prestige rather than by their ability to provide an affordable, quality education to all students, but especially underserved populations. The current hierarchy that places elite private colleges and universities at the top places the most weight on graduation rates, followed by academic reputation and faculty resources. These three attributes account for 62 percent of the ranking’s weight and the other 38 percent includes attributes like selectivity, alumni donations, and institutional resources, all of which set elite institutions up for great placement in the rankings.

Yet in this calculation, crucial metrics such as accrual and repayment of student debt, educational costs, and success of Pell grantees, play only a minor role. First, graduation rates for low-cost public colleges would improve if the calculation included transfer students, because those are the types of institutions where transfer students primarily attend. Second, the student indebtedness attribute looks solely at the proportion of borrowers in a graduating class and the average indebtedness amongst that cohort, and because elite institutions enroll greater proportions of high-income students, they will clearly outperform their peers. Lastly, costs of the degree are not accounted for in the U.S. News ranking metric at all which clearly aids elite private institutions where the annual cost of attendance can be as high as $84,000.

A January 2022 report from Third Way reexamined institutional rankings through economic mobility and found that elite private institutions underperform when it comes to mobilizing low- and moderate-income students. The Economic Mobility Index (EMI) unveiled in that report places more weight on the share of low- and moderate-income students that are enrolled, in addition the ability students have to recoup the cost of their degree through a price-to-earnings metric.

College remains the primary channel by which individuals hope to climb up the socioeconomic ladder, but commonplace ranking metrics like the aforementioned put very little weight on the success that institutions have in that endeavor. The EMI rankings in the table above make us question traditional metrics which place little significance on the success of low-income students and do not account for the fact that these students are more likely to borrow—the latter of which automatically penalizes the rankings for the institutions that serve them.

Conclusion

Because elite colleges have a high rate of student success, they are often overlooked when examining predatory or deceptive behavior in higher education. That status helps these institutions slide under the radar when enacting disingenuous corporate tactics, whether through union busting, price-fixing, secretive revenue-sharing partnerships with OPMs (online program management companies), or, as referenced in this report, through front-loading, cost underestimation, and indebtedness. The pervasiveness of the issues focused on in this report warrant foundational changes to how we regulate and fund higher education, define institutional success, and measure institutions against each other.

We hope the class action lawsuit will lift the veil on financial aid formulas for these types of institutions: how costs are underestimated and how free aid is awarded, not just in year one but for a students’ later years in college as well. We also hope highlighting the persistence of worrisome student debt trends at elite colleges will prove to student debt crisis deniers that they can no longer cherry-pick what counts as a debt-worthy degree. Elite institutions do not deserve the pedestal on which they currently stand—neither does any college that prioritizes profit or exclusivity over the interests of their students.

Endnotes

- Of note: 1) 75 percent of two- and four-year colleges award a higher amount of free aid to first-time full-time students than all other undergraduates—a sign that students are receiving less free aid in later years of college, otherwise known as front-loaded aid; 2) 69 percent of colleges are also underestimating off-campus ancillary costs, and 41 percent are underestimating the cost of off-campus room and board. Cost underestimation misinforms prospective students who consider affordability when comparing colleges.

- Because colleges do not report data specific to institutional scholarships, the front-loading analysis was done using a calculation that combines federal, state, and institutional aid together.

- For cost underestimation, the research team purchased an external dataset with cost-of-living estimations to compare against the cost-of-living costs reported by schools.

- Thirty leading private colleges were selected from Niche’s 2022 Top Private Universities in America; note that a few of the highly ranked institutions were not selected due to data limitations and regional considerations. The leading public colleges used for comparisons were the 30 with the lowest acceptance rates.

- Top public and private colleges were ranked by the average front-loaded difference over three academic years (2016-2017, 2017-2018, and 2018-2019) and the median was determined for each group.

Contact us at communications@jainfamilyinstitute.org to get in touch with the researchers.