Policy Microsimulations

Memo: Cost Simulations of a Fully-Refundable Child Tax Credit (CTC) 2022-2031

By Jack Landry and Stephen Nuñez

Download the full PDF here for best reading experience.

Current negotiations over the Build Back Better plan have stressed the importance of funding a consistent Child Tax Credit over the next decade. Since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) expires in 2026, the cost of the expanded American Rescue Plan Act CTC on top of the cost of extending the TJCA CTC becomes quite high (a total of $1.6 trillion over ten years, according to the CBO.) This has led to interest in potential compromise options that bring down the cost.

The current Build Back Better plan tries to curb the cost of the CTC by extending the full benefit level and refundability expansion in 2022, but then maintaining only the full refundability component thereafter (2023 onward). While the full expansion of the CTC delivers the most benefit to families, extending full refundability has the largest impact on poverty for the most vulnerable children. In this brief, we estimate the cost of full refundability of the Child Tax Credit between 2022 and 2031, paying particular attention to the cost and policy options when the TCJA expires. These estimates illustrate that it is possible to design a permanent Child Tax Credit that significantly curbs child poverty while leaving space in the reconciliation bill for other vital social programs over a ten-year horizon.

Changes to the Child Tax Credit when the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) expires

(For additional detail, see table one, page eight of the Congressional Research Service’s FAQ on the Child Tax Credit)

- The CTC value per child goes from $2,000 to $1,000.

- The CTC phase-out thresholds are reduced:

- $200,000 to $75,000 for head-of-household filers (single parents)

- $400,000 to $110,000 for married filing jointly

- Children with ITINs are allowed to take the credit. The TCJA status quo is that children must have SSN, but parents can have an ITIN.

- The CTC only includes 0-16 year-olds under both the TCJA and when the TCJA expires. The extension to 17 year-olds was specific to the American Rescue Plan Act.

- Other non-CTC tax code changes include a 50 percent reduction to the standard deduction and the restoration of personal exemptions.

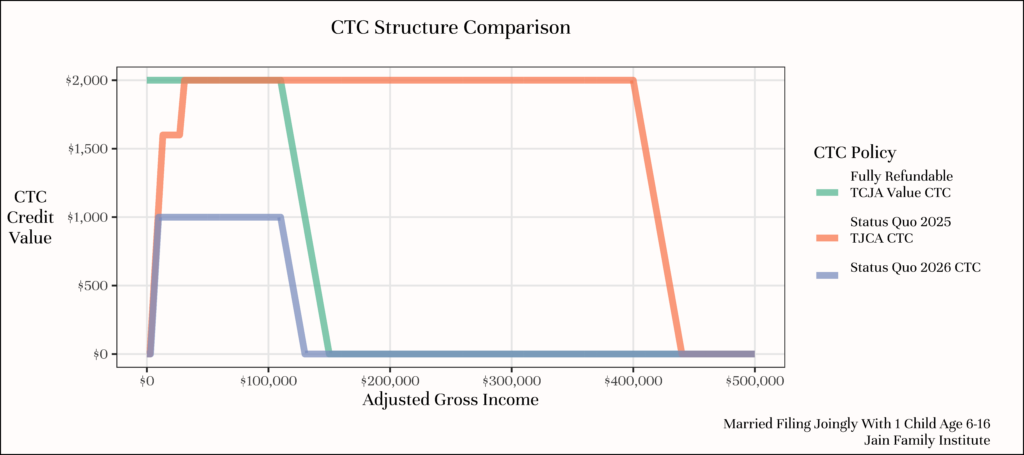

Figure 1:

The figure above compares different benefit structure options for the Child Tax Credit that modify the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act structure. The orange line shows the TCJA CTC structure, which will expire in 2025. The blue line represents the “status quo” CTC structure in 2026 if no further legislation is passed to either expand refundability or benefit levels. Finally, the green line shows benefits levels keeping the TCJA credit amount, adding full refundability, but letting the TCJA higher phaseout thresholds for upper-income parents expire.

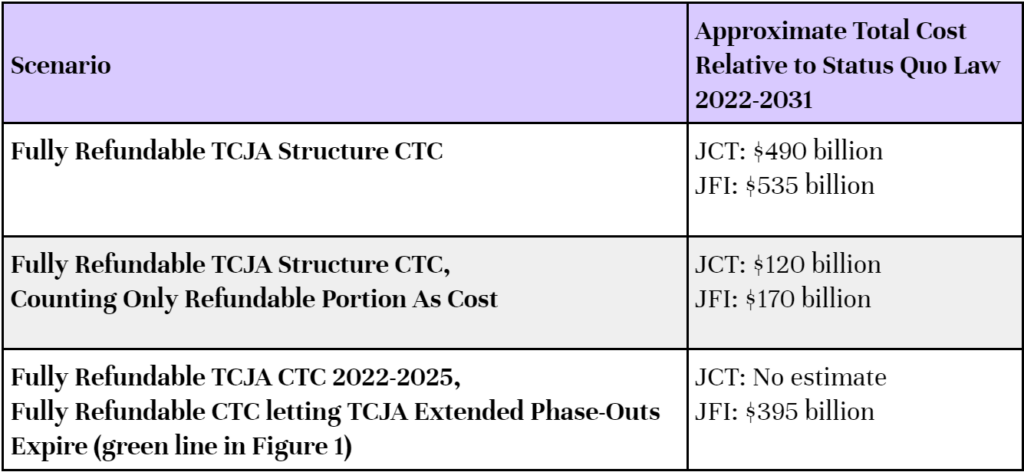

Figure 2:

These (Figure 2) cost estimates for each proposal provide a nuanced view of the ten-year horizon of potential costs for a fully refundable CTC assuming a first scenario of continued TCJA benefit levels and phase-outs past 2026, a second scenario isolating the cost of full refundability alone and assuming TCJA benefit phase-outs and levels may be renegotiated in 2025, or a third scenario in which CTC benefits are made fully refundable but are limited to low and middle income parents (green line in Figure 1).

All of these cost estimates compare changes to the CTC relative to the status-quo tax code. The cost of extending the CTC could be reduced further by making other changes. For instance, when the TCJA expires, personal exemptions return, which disproportionately benefit higher-income parents. Modifying or eliminating this provision would substantially reduce the cost of keeping an expanded, fully refundable CTC.

Comparative Cost Estimate Components

Joint Committee on Taxation Cost Estimate Breakdown

- TCJA CTC relative to prior law CTC: ~$74 billion / year

- CTC Full refundability during TCJA: ~$12 billion / year

- Cost of TCJA + full refundability 2027-2031: $12 billion / year + $74 billion / year = ~$86 billion / year

Jain Family Institute Cost Estimate Breakdown

- TCJA CTC amount, fully refundable without the TCJA phase-outs. (Orange line in Figure 1): $67 billion / year

- CTC Full refundability during TCJA: $17 billion / year

Jain Family Institute Cost Estimate Methodology

For costs that we simulated, we use a methodology called microsimulation. It begins with nationally representative survey data (the Current Population Survey, which is behind many important government statistics like the monthly unemployment rate) to simulate the population of tax returns. Specifically, we use the detailed family relationship and income information available in the survey to estimate each household’s tax return(s). Once we turn the survey data into simulated tax returns, we program changes in the tax code via the Policy Simulation Library’s Tax Calculator. This is a common tool used by many peer organizations, including the American Enterprise Institute, the Niskanen Center, and the Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy. To estimate revenue effects in the long term, we use survey data on 2018 incomes inflated to 2021 levels, which is unaffected by COVID-19-induced changes in the economy (or non-response bias, as 2019 incomes were based on a survey administered in the beginning of the pandemic in 2020). To estimate costs, we compare the total change in after-tax income with a given CTC policy to the status quo. We assume full take-up (all eligible children receive the benefit) for the purposes of estimating cost.

Comparison of JFI and JCT Cost Estimates

- JFI full refundability under TCJA: $17 billion / year

- JCT full refundability under TCJA: $12 billion / year

- JFI full refundability, TJCA benefits, and TCJA phase-out: $90 billion / year

- JCT full refundability, TJCA benefits, and TCJA phase-out: $86 billion / year

Differences between the JCT and JFI cost estimates illustrate the inherent uncertainty of cost estimates. Possible reasons for discrepancies include: We assume 100 percent take-up; it is unclear if the JCT assumes 100 percent take-up. It is also likely that the Current Population Survey (CPS-ASEC) data we use overstates the amount of parents with $0 income. The JCT has non-public IRS data on tax filing that should not have this potential limitation.