Cash at the State Level: Guaranteed Income Through the Child Tax Credit

Table of Contents

Comparative Features of State CTCs

- Amounts & Targeting

- Administrative Burden

- Inclusivity

- Frequency of Payments

- Unrestricted

- Financing

- Take-up Improvements

Summary

Since 2021, a significant number of states have passed fully-refundable child tax credits (CTCs) that include the lowest-income families with no reported labor income. This surge of public and policymaker support began alongside the historic federal 2021 CTC expansion in the American Rescue Plan Act, but crucially, it has persisted even as efforts to make the federal expansion permanent have faced political roadblocks. Altogether, eleven states now have active refundable CTCs, and legislation to create or expand such programs has been introduced in many others this year.

In this brief, we provide a comprehensive array of data on fully refundable state CTCs as a resource to lawmakers, researchers, and advocates. In addition to presenting descriptive information, we assess how successful recent expansions of the Child Tax Credit have been at following best practices in cash transfer benefit policy. While all state CTCs merit credit for creating a more inclusive, cash-based safety net, there is considerable variation in specific implementation between states and much room for further design improvements. We also discuss the political tenor of these reforms: the extent of bipartisan support in each state, support for unrestricted benefits, and the degree to which legislators situated their reforms within an explicit move toward “guaranteed income,” if at all. The experiences of each state offer lessons for other states interested in adopting refundable CTCs, as well as further expansions in states that have already adopted these credits. We estimate that these credits will likely be durable additions to state benefits and will increase cash assistance over the long term, as was true for refundable state EITCs.

Key Takeaways

- Eleven states have passed refundable CTCs ranging in value from 300$to $1,750 per eligible child. Some are targeted at low-earner families, while others are universal or phase out at high income levels.

- While the states that have passed CTCs have Democratic majorities in their state legislatures, many of the credits have passed with substantial Republican support.

- Some states have relatively small benefits, but are likely to be expanded: Of the eleven states with refundable CTCs, seven have already significantly expanded them.

- Beyond benefit amounts, the state CTCs vary in their income and age targeting, inclusion criteria, and administrative burden. We point to ways through which states can reduce administrative burdens, create monthly payment options, and ensure immigrant children receive benefits. Such changes align with best practices from the empirical literature on direct cash assistance.

Overview

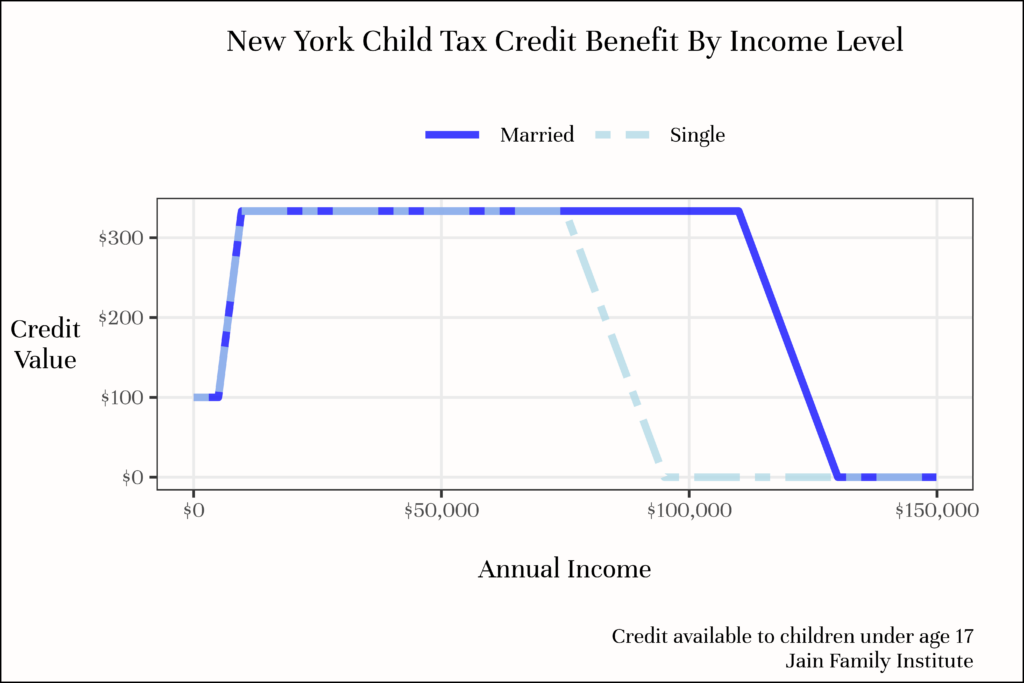

While the federal child tax credit expired in 2021, efforts to provide cash assistance to the lowest-income children continued to hold political resonance, particularly because of the dramatic anti-poverty and equity impacts that the federal program had. In the wake of the federal program’s expiration, eleven states have passed a refundable child tax credit.1 Not all states use this exact terminology: for instance, California calls its credit a “Young Child Tax Credit” and New York refers to its credit as the “Empire State Child Tax Credit.” Most inclusively, we count Massachusetts’s dependent credit as a child tax credit. It gives a refundable $440 credit for children under the age thirteen, but also includes dependent adults over the age of sixty-five.

These are not the first state-level benefits for families in the tax code. However, they distinguish themselves from other long-running benefits for families with children (e.g., exemptions, deductions, and non-refundable child tax credits2 We focus on refundable child tax credits in this brief, though we may not always specify “refundable” in each reference to state CTCs.) by benefiting lower-income families who do not have any income tax liability in the form of a refund. Most states have a standard deduction and relatively low-income tax rates, which means taxpayers do not owe state-level income taxes until they reach a substantial level of earnings. If a family does not have enough income to owe any income tax, then they do not have access to exemptions, deductions, and non-refundable credits either. A refundable credit benefits low-income families over and above their tax liability, giving them a refund even if they do not have to pay any income tax.3 While many families do not have state income tax liability, they still pay a significant share of their income to sales taxes, and pay some of the incidence of property taxes in the form of higher rents.

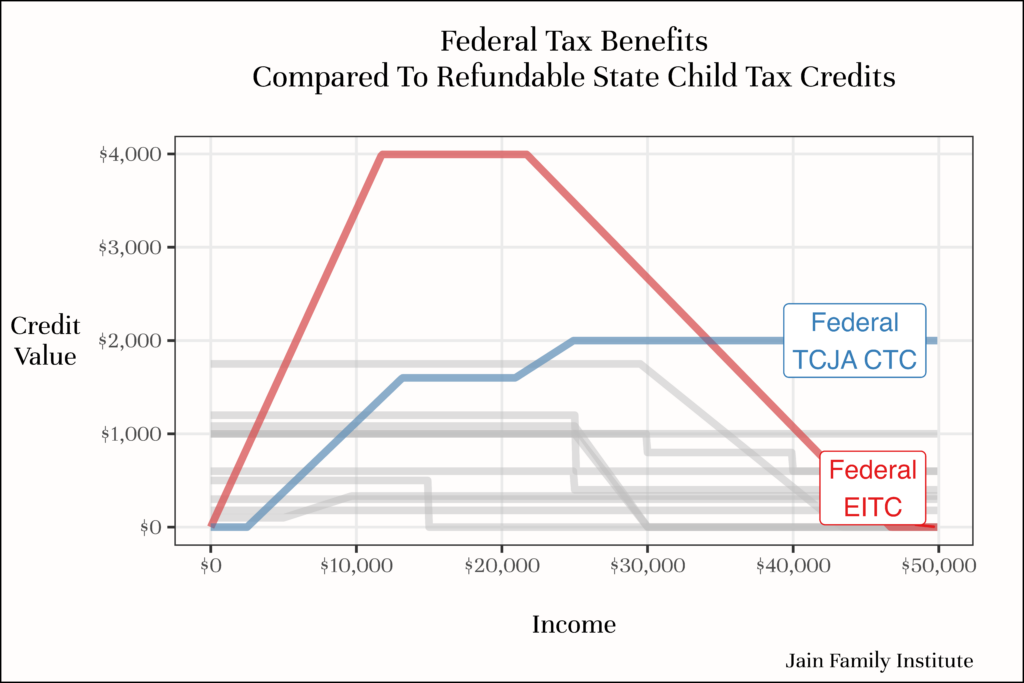

In addition to non-refundable credits, deductions, and exemptions for families with children, many states have implemented a refundable Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). This tax provision benefits families with low incomes and without an overall tax liability in the form of a tax refund. However, EITCs only support the “working poor”–they generally require families to earn over $10,000 to receive the maximum benefit and don’t offer any benefits to families out of the labor force. By contrast, newly implemented refundable state CTCs give the lowest-income families with no taxable income the full value of the benefit. This guarantees families with children some minimal level of income—even if they have no labor market earnings, they are eligible to receive a state’s Child Tax Credit.

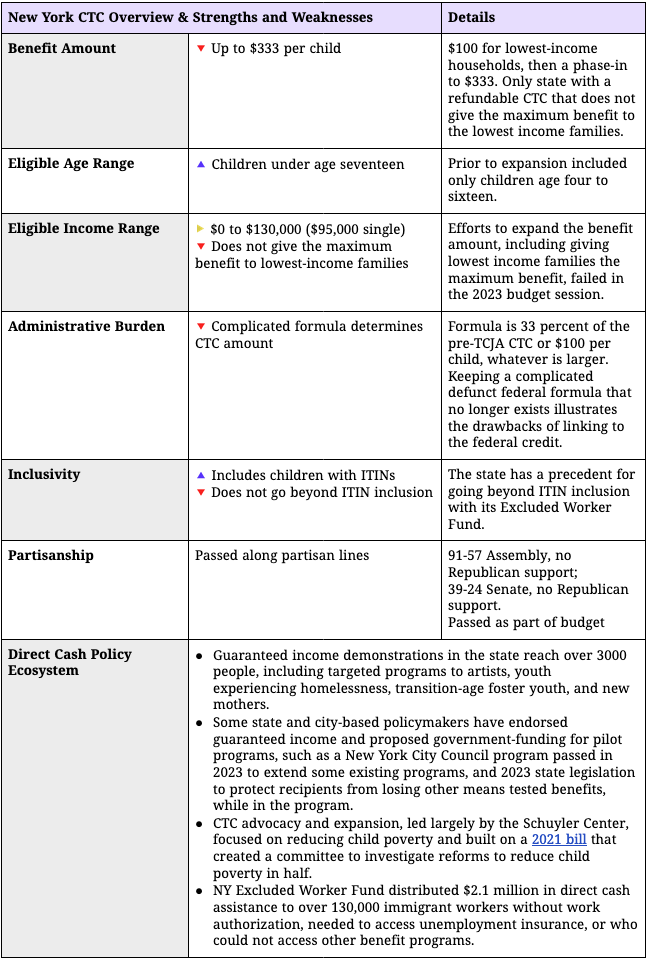

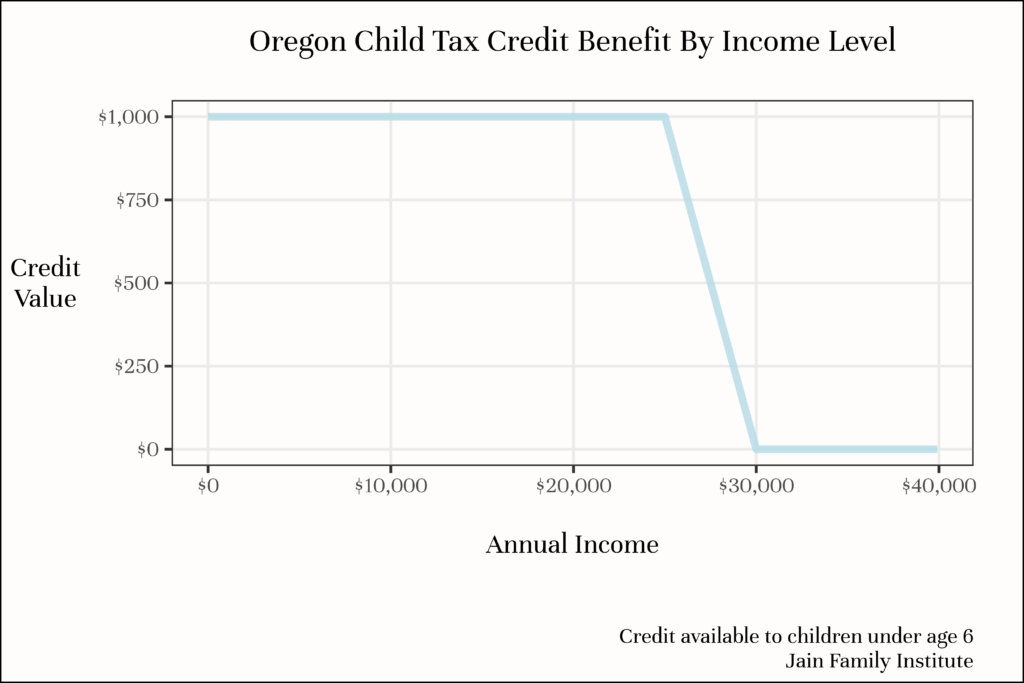

The figure below shows how benefits change by income level in the eleven states with refundable CTCs. While the specifics of each state vary, all offer some benefit at $0 of income, and all but New York offer the maximum benefit at $0 of income. Importantly, these benefits do not only include families with no income—while phase-out points vary, all states provide some benefit until at least $15,000 of income, with some providing benefits at very high income levels or even universally. We break down the parameters of each state’s CTC at the end of this report (skip ahead here).

By providing a benefit to families with $0 of income, state CTCs also help fill a gaping hole in the federal cash safety net.4 One exception to this general pattern are state EITCs that extend eligibility to ITIN filers, who are not eligible for the federal-level benefit. In 2020, California and Colorado became the first states to allow ITIN filers to claim their state’s EITC. The District of Columbia, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington have also made ITIN filers eligible for their state EITC. Families are not eligible for any benefit from the federal CTC until they have at least $2,500 of income; they only receive the full $2,000 per child when they have upwards of $25,000 of income. Only in 2021, with the American Rescue Plan Act, did the federal government remove its income requirement—but the change was not renewed after one year. While the federal EITC provides more benefits for low income families than the CTC, it does not apply to families without earnings from work. Finally, though the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program could provide cash assistance to families who are out of work, a combination of eroding federal funding and state decisions to divert funds away from cash assistance has resulted in a situation where just one in five families with children in poverty receiving any cash TANF benefit.

The graph below highlights the values of federal CTC and EITC for families with one eligible child by income level. The gray lines represent individual state CTCs. While the structure and generosity of state CTCs vary, they all help fill the gap in the federal safety net by providing a significant benefit at $0 income.

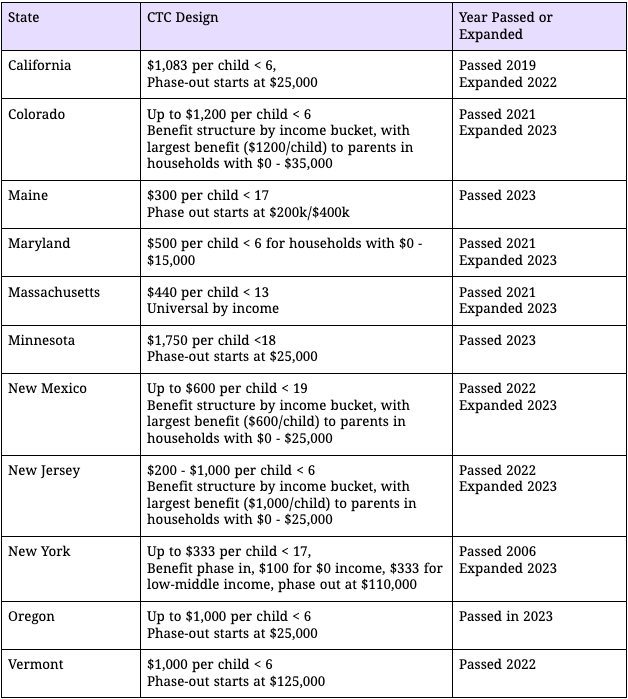

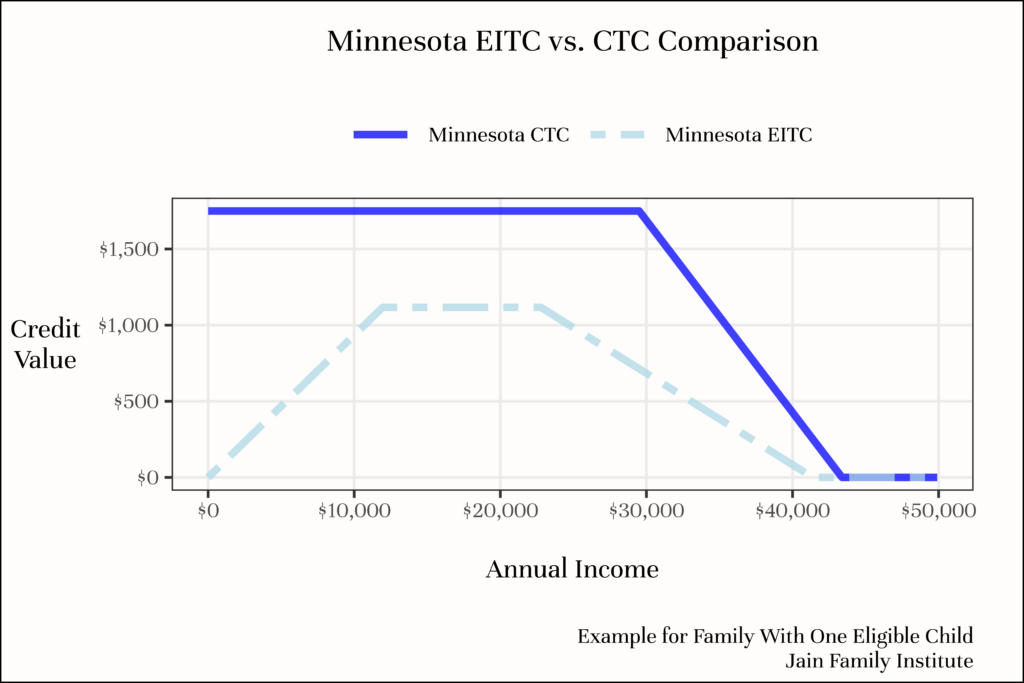

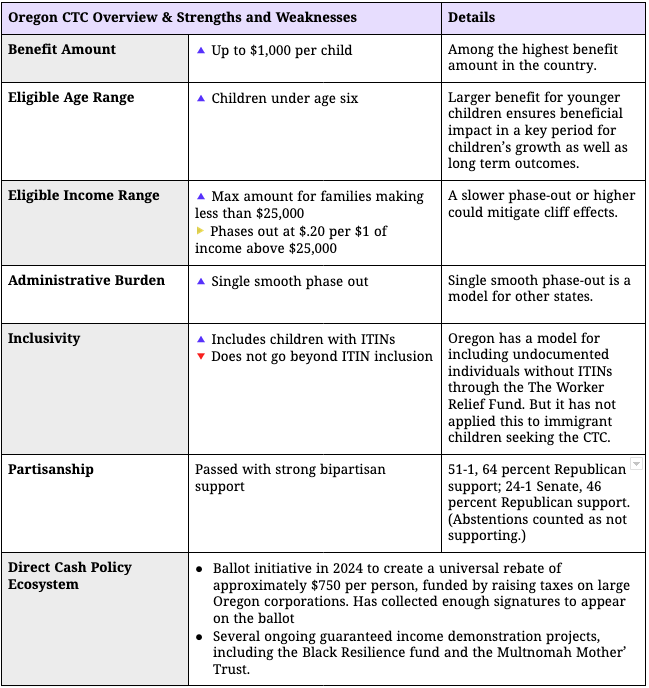

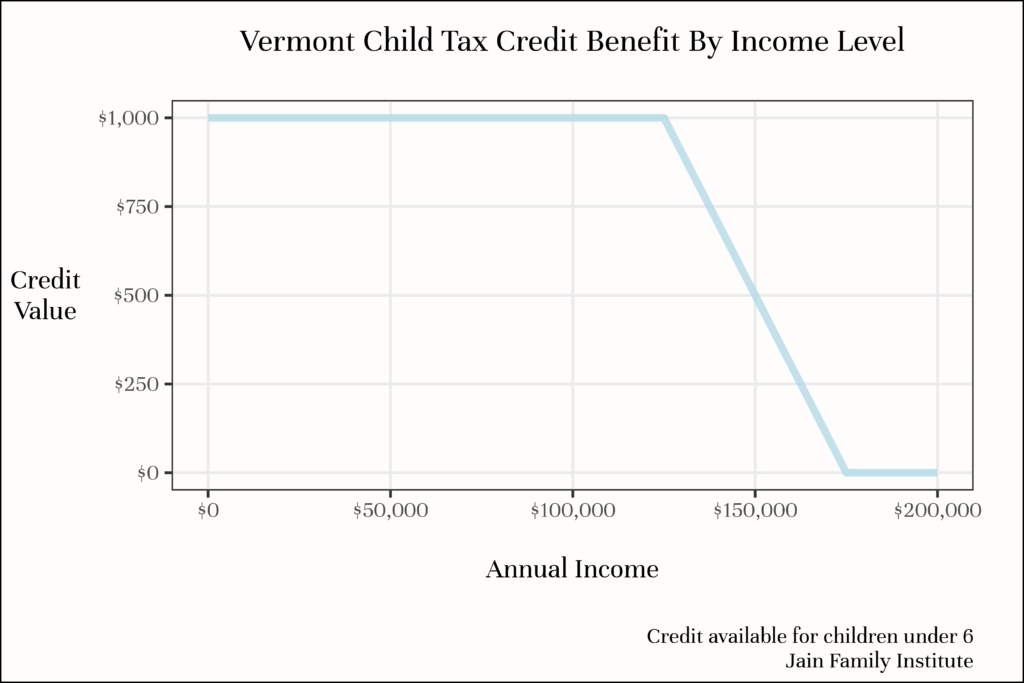

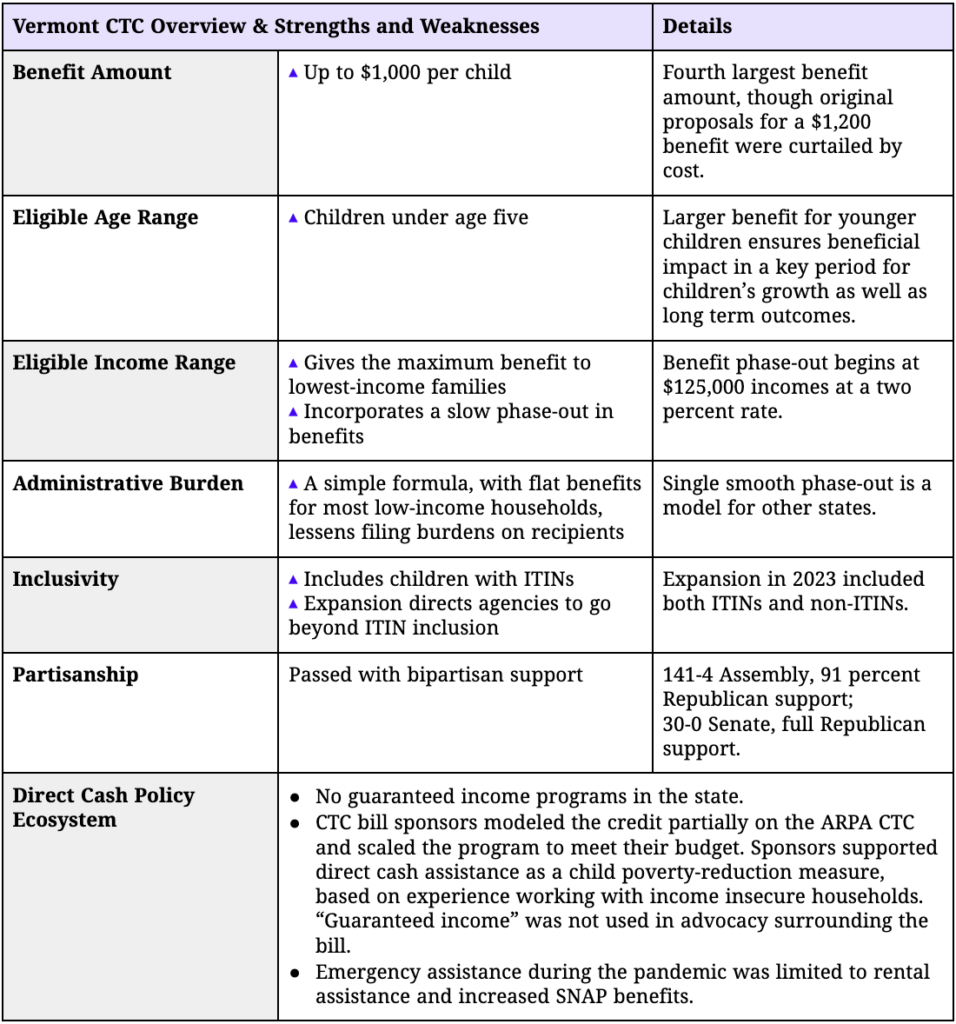

As of 2023, eleven states have fully refundable CTCs with some benefit to families with little to no income. We provide state-by-state details below (skip here to view state-specific data). Here are a few key points of comparison: Minnesota closed its 2023 legislative session by passing the largest CTC in the country, $1,750 per child under 17, for households making $0 to $35,000 each year. The second most generous benefit was passed in Colorado, with a benefit of $1,200 per child under six, for households below $35,000 in income, with smaller amounts available at higher income levels. The Vermont CTC passed in 2022 is noteworthy for its comparatively simple structure: it offers a flat $1,000 per child with a slow phase-out above $125,000 in income. The credits also vary in administrative burden, with the New Jersey CTC requiring just a quarter page of additional questions on one’s tax filing, as opposed to the 2022 Colorado credit, which required three additional pages. While monthly or quarterly payments face many administrative obstacles, legislation in Minnesota and Oregon leave open this possibility.

Variation in the income eligibility criteria reveal that legislatures have not completely lost their desire to target the poor. However, deservingness criteria no longer limit eligibility to a narrowly defined “working poor” family—a major shift in state approaches to benefits which diverges from the federal status quo. As the graph shows, in Vermont, the income phase-out structure roughly models after the 2020-2021 economic impact payments and the expanded CTC. By contrast, the most generous benefits in Colorado and Minnesota go to families with incomes around the federal poverty line. In Massachusetts, a more modest benefit is administered universally to all parents, while Maryland has the most heavily income-targeted CTC—accessible only to parents with at most $15,000 in income between them. We summarize the general parameters of each state CTC in the table below. For more detail on each state, skip to our state-by-state section.

Comparative Features of State CTCs

We compare the state policies based on the following key parameters for direct cash assistance. A wide breadth of research on cash assistance within the past several decades—as well as broader research on US social safety net programs—points to the importance of these comparative policy features:

- Amounts and targeting: While some studies show that even small cash transfers can have significant effects on long term economic outcomes, larger amounts will necessarily have a greater impact. However, lawmakers are often constrained by limited budgets, leading to choices around targeting criteria: eligible income levels, age ranges, and benefit phase-out rates. We discuss evidence around targeting and avoiding benefits cliffs.

- Administrative burden: States should avoid complicated formulas and/or eligibility criteria, which make it more difficult to claim the credit and complicate other reforms that could help ensure all families eligible for the credit actually receive it. States have implemented CTCs with as little as one added line on a 1040 tax filing.

- Inclusivity: States should not exclude any income-eligible families from receiving the benefit due to immigration status. Many states have taken positive steps toward inclusivity by making families with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITIN) eligible to claim their CTC. However, states should explore alternative options to provide proof of eligibility for families without an ITIN or SSN, which can be very difficult to obtain.

- Frequency of payments: Distributing payments more frequently than the traditional lump-sum refund at tax time may have some benefits. Indeed, more frequent payments are preferred by many parents. However, moving away from the traditional, annual tax structure may cause a reduction in recipients’ SNAP benefits, and comes with an array of different administrative challenges, like allowing families to update bank account information during the year. States interested in this option should carefully study all the implementation requirements, invest in administrative capacity, and allow recipients to opt-out of a more frequent payment option.

- Unrestricted: Cash transfers only differ from existing forms of benefits and social insurance if recipients are allowed to use the benefit as they see fit. While other programs specifically target food insecurity (WIC/SNAP), housing access (Section 8, HCVs), or other predicted needs in poverty, the CTC is unique in allowing parents to spend the cash benefits on what their children need. Restricted or in-kind benefits introduce inefficiency, paternalism, and often administrative burden.

- Financing: States can sustainably finance CTCs via tax increases and benefits consolidation. States that rely on economic growth to pay for a CTC may have to face hard decisions about what to cut during a recession.

- Take-up improvements: Thus far, states have passed refundable CTCs without parallel efforts to ensure all income-eligible families actually receive the credit. We suggest three categories of strategies that states can use to increase takeup: 1) information or awareness campaigns; 2) simplified filing portals; 3) automatic payments based on enrollment in other safety net programs.

Beyond the comparative policy design parameters, we also discuss the politics of state-level cash assistance, noting in particular its bipartisan appeal. Finally, in our state-by-state section, we provide a general view of the ecosystem of cash assistance efforts in each state (for example, guaranteed income pilots, emergency cash aid, etc.), pointing to support for guaranteed income or other income supplement programs. Throughout this analysis, we provide recommendations based on existing evidence, while noting some outstanding research questions.

Amounts & Targeting

The core design questions for a state child tax credit are: Who receives the benefit, and how much do they get? These questions are answered by a few different policy levers: 1) the benefit amount; 2) income qualification criteria, including both when the benefit phases out and how fast it phases out; 3) any additional qualifying criteria, like limiting the benefit to young children or limiting the total number of children that can be claimed. For a fixed budget, making one lever more generous requires making others less so. States must answer questions like: Is it preferable to have a larger credit for children under age six, or a smaller credit that includes all children under eighteen? A credit that phases-out quickly but provides the maximum benefit over a wide income range, or a credit that phases out slowly but provides the maximum benefit around a narrow income band? A larger credit that only includes the lowest-income families, or a smaller credit that also includes more middle-income families?

Benefit Amount

It is easiest to provide guidance on benefit amounts: All things equal, larger amounts are better. Larger credit amounts will cause more reductions in material hardship and poverty.5 The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University report on state-level child tax credits puts specific numbers on how much different credit amounts reduce poverty in each state. Unconditional cash transfer research is unambiguous about positive impacts from cash writ large, but it’s not yet clear at what point additional cash has diminishing marginal returns or impacts.6 Research is outstanding on any variation in effect sizes corresponding to larger or smaller amounts (for example, larger or smaller impacts on income, health, etc.). There are currently over 70 active guaranteed income demonstrations across the country with ongoing experimental evaluations. Some of them provide $500-600 each month, others $1,000 each month or more, with varying income eligibility criteria. In coming years, a meta-analysis of these varied approaches would help to answer this open question. However, at the benefit levels states have currently adopted (maximum amounts per child range from $180 to $1,750), it’s very unlikely that an extra dollar spent on a child tax credit will have diminished effectiveness. The cost of raising children is far higher than $1,750, and it’s implausible that these benefit amounts would be a significant work disincentive.

It’s important to note that even small amounts of cash can have a significant positive impact on children’s lives. No CTC is so small as to not be worth pursuing. For instance, one study on the long term effects of cash transfers found that children who received a one-time transfer of $1,300 around infancy earn two to three percent more in their twenties. In recent years, nonprofit programs like the UpTogether’s (formerly the Family Independence Initiative) cash infusion program and LIFT’s family goal fund have both shown noticeable impacts from quarterly payments of just $150 for hundreds of low income families: increased savings, fewer late fees on bills, and spending more on health and educational programs.

Income Targeting

Our core recommendation is that states should ensure the lowest-income families receive the full credit. While this brief concentrates on refundable CTCs, refundability is only a prerequisite for the low-income families benefitting—not a guarantee. States can create other criteria that limit or deny benefits to low-income families. For instance, New York’s refundable CTC has a phase-in: the lowest income families receive $100 per year for every eligible child, while higher income families receive a $333 credit. Similarly, before Colorado’s recent CTC expansion, their credit offered a percentage of the federal benefit, which gives no funds to families with less than $2,500 in earnings and does not give the full benefit until families reach upwards of $25,000 in earnings.

For a given state budget, the more families with relatively higher incomes included in the CTC, the smaller the benefit must be. Families with the lowest incomes are the most in need of extra support. And those with no income from work have virtually no cash safety net. However, families with extremely low or zero cash income are not the only ones in need of income support; there is little research showing diminishing marginal returns to benefits that go up the income ladder. Many existing benefits are highly targeted at the lowest income families: adding a highly targeted CTC can perpetuate a dynamic where safety net programs move families above the poverty line, but provide no support up the income ladder on the road to more long term economic stability.

Among states that have implemented fully refundable tax credits, there is wide variation in how much the CTCs target the lowest-income families. Some credits are highly targeted. For instance, Maryland’s CTC only includes families with incomes below $15,000 a year. In contrast, New Mexico provides at least some credit to all families while giving lower-income families larger amounts. And Massachusetts has a totally universal structure, providing the same benefit regardless of income.

One potential compromise that levels the trade-offs between benefit size and targeting is to phase out the credit at an income level where families are no longer eligible for other important safety-net benefits. This rule of thumb would prevent families from getting cut off from the CTC at the same time as they are losing other benefits as their income rises. Income eligibility levels for benefits can vary between states: we lay out general guidelines here but can provide more specific analyses to state policymakers and advocates outside of this brief.7 Those interested in state-specific analysis can reach us at: jack.landry@jainfamilyinstitute.org.

Three important income support programs can phase out at higher income levels: SNAP, housing assistance programs (namely Housing Choice Vouchers and Public Housing), and the Earned Income Tax Credit. SNAP and housing assistance serve a small fraction (five percent) of households reporting an annual income between $40,000 and $50,000 per year.8 Details of this calculation are provided in the appendix. At $30-40k, 20 percent of households receive SNAP and eight percent receive housing assistance and at 20,000-$30,000 of income, 40 percent receive SNAP and 13 percent receive housing assistance, respectively. However, at this income range, families remain in the phase-out region for the Earned Income Tax Credit: EITC eligibility extends to $63,398 for married couples with over three children, and at least to $46,500 for all families with children. To avoid phasing out at the same time as other benefits, states will need to retain the credit until $64,000 a year.9 Eligibility for government health insurance programs can go higher than this point. For instance, The median state’s CHIP eligibility goes to 255 percent of the poverty line, which is $76,500 for a family of four. However, at this level of income, many families are likely offered (or are enrolled in) employer sponsored coverage. However, it is not unreasonable to phase out a CTC at the same time the EITC phases out, as long as the CTC phases out slowly. In general, it is more important to slowly phase out a state CTC as a family’s income increases (covered in the next section) rather than to start phasing it out at an arbitrary income level.

Another potential anchor point for phasing out a CTC is a percentage of the average supplemental poverty line for families with children in their state. This method emphasizes a level of need rather than harmonizing a program with other safety net benefits, and using the supplemental poverty line rather than the official poverty line recognizes that needs vary based on housing cost differences between states. At the national level, the average (100%) supplemental poverty line for families with children is $37,555. 150% of the line is $56,333, and 50% is $18,778.10 Author’s calculation using the 2022 CPS ASEC data adjusted for inflation.

Importantly, means-testing (e.g. a credit that phases out at a certain income level) is not the only way to ensure that low-income families receive a sizable benefit. A state could pair a universal CTC with a small but broad-based tax increase. While wealthy families would receive a CTC, the tax increase will mean they do not benefit on net, ensuring the program is sustainably financed on the back end.

Universality has several benefits. First, progressive taxation can help avoid extremely narrow targeting or a fast phase-out. Second, it recognizes that all families are deserving of a child allowance.11 Since a tax increase affects taxpayers regardless of whether they have children, but a universal CTC is only for families with children, families with children are slightly better off at all points on the income distribution. Third, it gives all parents a stake in preserving and expanding the benefit, rather than just low-income parents who have the least political power.12 While universal benefits are likely more politically durable than a benefit targeted exclusively to poor families, it is not clear that all means tested benefits are less politically durable than universal benefits.

In other contexts, JFI has argued that another benefit of universality is that it eases administrative burdens and better ensures high takeup by eliminating means testing. In the case of a state-level child benefit, it is unclear whether universality will have these benefits. Even if there is no income testing, there still needs to be an enrollment process to verify state residency and which household is caring for a given child, as many children do not have the same custody arrangements from birth.13 States can also eliminate the income testing part of the filing process via a nonfiler portal, covered in the section on increasing benefit takeup. One national child benefits administrator has far more benefits than fifty different state systems.14 For states without an income tax, creating a dedicated child benefits administrator has more merit, as a CTC cannot simply be added into the existing income tax system.

While it is possible on paper to provide a large universal CTC with targeting and financing via broad-based taxation, this can be a harder political lift. It may not be a coincidence that the only state to provide a universal CTC (Massachusetts) also has one of the smallest benefits.

Phase-out Rate

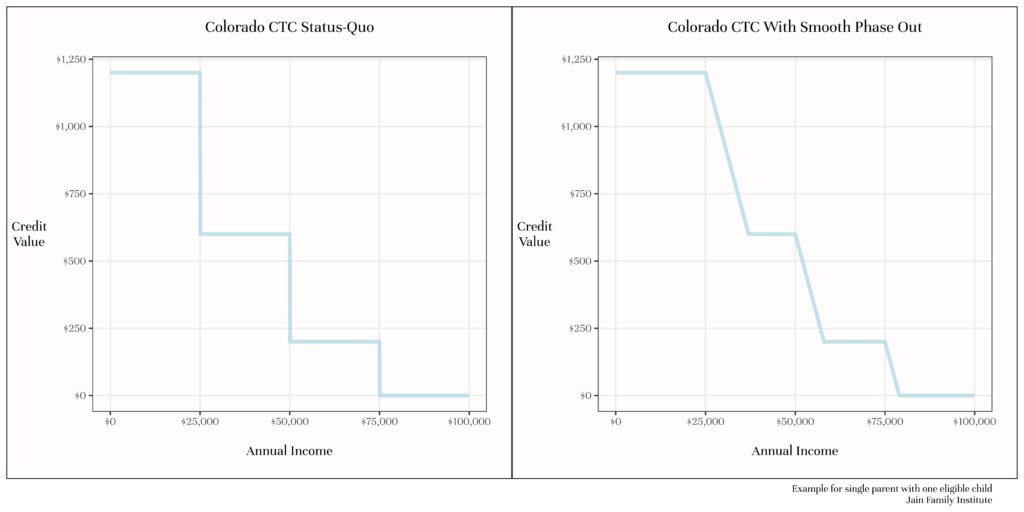

More important than where a state phases out a benefit is how fast they phase it out: states should slowly reduce the value of a credit as a family’s income increases. Some state CTCs sharply cut off benefits above a certain income level. For instance, Maryland’s CTC gives $500 per child credit to families with income below $15,000, but nothing to families above that income point—even as there is no significant economic difference between those on either side of the threshold. Sharp drop-offs at an arbitrary level create a cliff effect, where some families would paradoxically be better off not earning more money from work because it causes them to “fall off” the CTC benefits cliff.

CTCs with benefits cliffs do have one benefit: simplicity. Parents in a given income range get a specific benefit per child, without any complicated calculation. However, slowly phasing out a benefit is also a simple method to implement—and it avoids any cliff effects. Vermont provides a good example. For every additional thousand dollars of income above $125,000, the credit is reduced by twenty dollars—an easy-to-follow table provides the exact amount of credit at different income levels (see appendix figure 1). California has a similar phase-out structure but implements it with a few easy-to-follow calculation steps (shown in appendix figure 2).15 While better than a cliff, California phases out their credit very quickly around the same point other safety net benefits are phasing out and before many families with children will have enough income to be above the state’s supplemental poverty line.

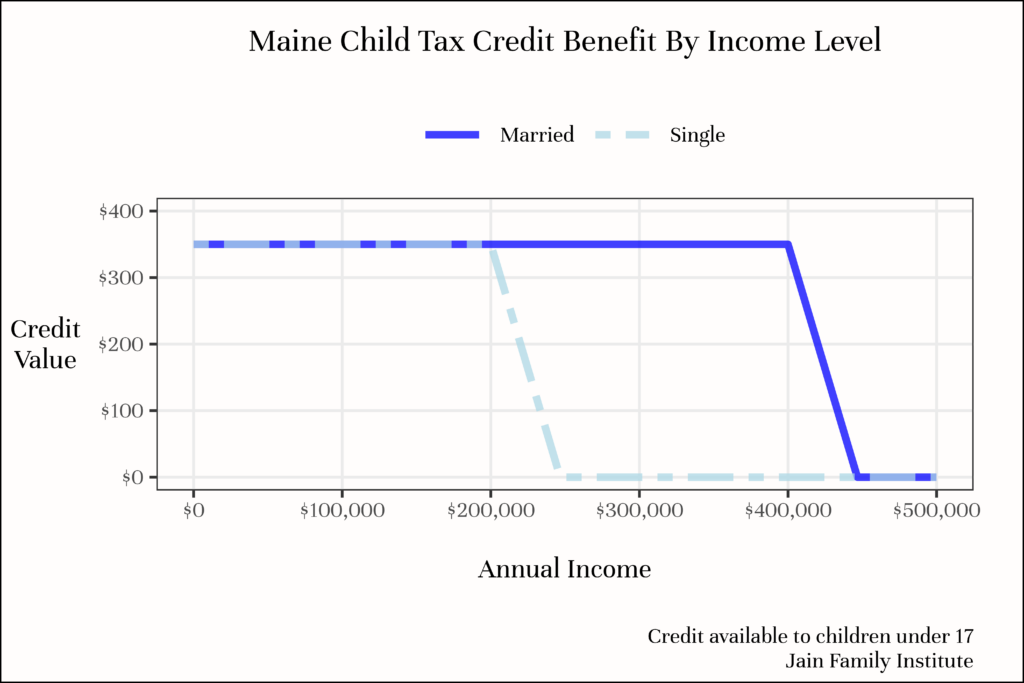

While having a single-phase-out point is the simplest option, slow phase-outs can easily be incorporated for states that want to set different credit levels at different income ranges. The figure below shows how this could work in Colorado. Rather than having a sharp drop in benefits between income thresholds (the status quo in the left panel), a credit can phase out so that a family receives $.05 cents less credit for every additional dollar of income (the proposed reform in the right panel). Rather than suddenly receiving $600 less per child after making slightly more than $25,000, the credit slowly reduces in value between $25,000 and $37,000. There are similar slow “phases-down” of the credit, rather than cliffs at $50,000 and $75,000. This will increase benefits for some families and increase the total cost of the program, but not dramatically. Shifting the point where the benefit starts to phase out to a slightly lower income level could make the change cost-neutral, slightly decreasing the benefit for some families while slightly increasing it for others.

While any gradual phase-out is better than a cliff, states should also aim for slow phase-outs. Reducing the value of a benefit as income increases has the same effect as a tax.16 For instance, if a CTC is phased out at $.25 cents for each additional dollar of income, but there is no tax on earned income, a family’s tax rate is effectively 25 percent. Total resources (CTC plus employment income) increases by $.75 cents per dollar of employment income, equivalent to not phasing out the CTC at all, but imposing a 25 percent tax on employment income. For this reason, a benefit phase-out rate is often referred to as an implicit marginal tax rate. In isolation, most phase-out rates (e.g. $.25 cents for each additional dollar of income) are reasonable. However, the phase-out rate of state CTCs, when compounded with other programs and income taxes, can create an unduly high implicit marginal tax rate for some low-income families. This is another reason why states should consider phasing out CTCs at relatively higher income levels, beyond that of other safety net programs. If a state begins phasing out a credit at a lower income level, it’s particularly important to phase it out slowly.

States that phase-out their credit quickly should phase out the total credit amount rather than the credit amount per child to avoid high implicit marginal tax rates for families with higher numbers of eligible children. For instance, if a state phases out a credit per eligible child by reducing it by $.20 for every additional dollar of income, it provides a reasonably low implicit marginal tax rate for a family with a single eligible child. However, the phase-out compounds for every additional eligible child—a family with three eligible children would lose $.60 of total credit ($.20 per child) for every additional dollar of income. Phasing out the total amount of credit ensures that families with more children do not see their benefits reduced faster than smaller families. However, this is not necessary for states like Vermont who phase-out the benefit very slowly ($.02 for every additional dollar of income).

One prominent justification for slow phase-out rates are their potential impact on work. Fast phase-outs create high implicit marginal tax rates, which can be a disincentive to work—adding income will result in a loss of a significant share of your benefits. In our view, this justification is overstated. Research shows that the vast majority of families do not face punitively high marginal tax rates. And families are unlikely to have either the knowledge or control over their exact earnings to work only a certain amount that maximizes their benefits. While a thorough review is beyond the scope of this brief, there is scant evidence that the fast phase-out rate of safety net programs significantly disincentivizes work. Much of the evidence that does exist does not hold up under close examination

The more important justification for a slow phase-out rate is basic fairness. Low income families should not face higher marginal tax rates than the wealthy. Even if it does not affect decision-making, it is wrong to quickly withdraw a benefit at an arbitrary income level. There is no magic income level at which families no longer require support—slowly withdrawing a benefit as income increases is a recognition of that reality.

Age or Other Targeting Criteria

Many states choose to target their CTC to younger children under age six. This form of targeting has a strong evidence base. While older children would be positively impacted by a state CTC, states with a limited budget should consider limiting eligibility to children under six. Alternatively, states could give a larger credit to families with younger children.

Families with younger children are more likely to be living on incomes below the poverty line. Moreover, research shows that poverty among younger children is especially damaging to well-being in adulthood. For instance, the National Academy of Sciences roadmap report on child poverty reports that “The weight of the causal evidence indicates that income poverty itself causes negative child outcomes, especially when it begins in early childhood and/or persists throughout a large share of a child’s life.”

Often, the drawback of targeting is that it’s complicated to execute, placing administrative burdens on recipients that cause many eligible people not to apply. These critiques do not apply to targeting young children. Age is a simple enough criterion to administer. This form of targeting may even help set the stage for future expansions. Giving a large benefit to younger children makes a credit more salient than spreading a small benefit around to children of all ages. And parents whose children age out of receiving the credit create a natural constituency for demanding an expansion of the eligibility criteria.

Some states have implemented other targeting criteria that should be avoided. For instance, states should avoid reducing costs by limiting the number of otherwise eligible children a family can claim.17 California currently limits families to claiming one child, and Massachusetts limited families to claiming two children until its recent 2023 expansion. Families with more children have higher costs, even if they receive some benefit from some economies of scale, an additional child will always require more resources. In fact, families with three or more children are more likely to be below the poverty line than those with one or two children.18 Author’s calculation using supplemental poverty measures, Current Population Survey 2019. Similar “family caps” for welfare have a racist history—lawmakers implemented them to try to deter low income, primarily black women from having more children.

Other narrow targeting criteria should also be avoided. For instance, Maryland offers a credit for families with disabled children making less than $6,000 a year.19 Maryland expanded its credit in 2023 to include all children ages 0-5 in families making less than $15,000 per year. While this group is certainly in need of cash assistance, others are too. Second, the disabled criteria can be difficult to prove to tax authorities, shifting the administrative burden on recipients, and preventing other eligible families from getting the credit all together.20 In practice, the complexity of any given child tax credit formula is considerably reduced by paid tax preparers and software–few families prepare their returns by following IRS instructions without assistance. Third, it’s very difficult to increase takeup for a group that is so narrowly targeted.

Administrative Burden: Simple Credit Structures

States should opt for simple structures to determine how much credit a given family receives. A fully refundable credit that has a single phase-out point and only uses dependency status and age as qualifying criteria for children is ideal.

The status-quo federal CTC does not follow this example: it has a very complicated phase-in structure. Families receive $.15 cents of credit for every dollar of earned income above $2,500, up to $1,600 of credit. To receive the last $400 credit of the $2,000 per child credit, families must have a net tax liability, which will vary depending on other aspects of their tax return. Moreover, the total amount of credit a family is eligible for depends on both their income and number of eligible children, which means two households with the exact same income could receive a different amount of credit per child. Instructions for claiming the credit span nine pages, and the form requires up to twenty-seven calculation steps.

This complicated formula adds to the difficulty of filing a tax return. However, simple structures have many benefits besides easing the administrative burden. It makes the overall benefit more legible to beneficiaries, so families can know how much to expect and legislators can explain the benefit to their constituents. Most importantly, it makes other interventions to increase takeup possible, such as a nonfiler portal and automatic payments.21 This is covered in more detail in the takeup section.

Inclusivity: Including Children Without Social Security Numbers

The federal child tax credit is currently restricted to children with Social Security numbers valid for employment. In practice, this restricts the credit to citizens and immigrants with federal documentation status (though a small number of documented immigrants are not eligible for an SSN). This was a change made in 2018 with the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act; previously, children with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number were eligible to receive the Child Tax Credit.

States have the discretion to set their own criteria for eligibility for a state-level child tax credit—they do not need to restrict the credit to SSN holders. Inclusivity is a policy design and implementation choice that reflects equitable social policy and ensures benefits across a community. In contrast, the historic exclusion of racial and ethnic minorities from social services has produced a legacy of compounding inequality and cyclical poverty. Greater inclusion also contributes to more positive economic outcomes from cash assistance programs, as all individuals participate in the economy. A review of evidence from the National Academy of Sciences around benefits-use among immigrants found that second-generation immigrants are among the strongest fiscal and economic contributors in the country. In addition, inclusion creates equitable benefits recovery as all families, regardless of documentation status, pay into the tax system.

Most state CTCs allow children with ITINs to receive the benefit (Maine is the lone exception). While a positive feature of some state tax credits, one important limitation of ITIN inclusion is that ITINs can be very difficult to obtain. The IRS requires applicants to have original documents or exact certified copies with an official stamped seal proving their identity from the original issuing agency, and these cannot be past their expiration date. The documents have to be reviewed at a small number of IRS Taxpayer Assistance Centers or by Certified Acceptance Agents or they have to be mailed to the IRS along with a paper tax return.

States should go beyond ITINs and expand eligibility to anyone who can demonstrate residency. SSNs and ITINs provide an important check on organized fraud–criminals who seek to submit fraudulent returns would have to use a stolen Social Security or ITIN number. However, even a fairly burdensome state-level process that provides an alternative to ITINs but guards against fraud could provide significantly more access than an ITIN alone.

Some states have modeled more inclusive benefits access across their safety net systems. Vermont’s recent CTC expansion is an example. While the original bill mirrored federal SSN eligibility requirements, they recently passed a law that both expanded access to ITIN holders and directed the state tax agency, “to provide a process” by which families without SSNs or ITINs could claim the credit. While Vermont agencies may be mirroring legislator’s intentions to maximize inclusivity without administrative hurdles, other state agencies may require more direction or specific regulation to include non-ITIN children. Policymakers should consider partnering with immigrant access organizations to help create specific processes.

Several other states have more well-developed benefits programs that were created during the pandemic to serve undocumented residents excluded from federal benefits programs, such as unemployment insurance and the economic impact payments. For instance, New York’s excluded worker’s fund required applicants to prove their identity, residency, and loss of employment income, but accepted a wide array of documents to this end. While the requirements were not easy to meet, they allowed a broader range of documentation than ITINs alone, which likely increased access for many immigrant workers.

In Colorado, pandemic unemployment and upheaval among contract and service workers, many of whom were undocumented and unauthorized workers without ITINs, motivated an effort to establish a Benefit Recovery Fund. The fund was originally philanthropically funded in 2020 (the Left Behind Workers Fund) but became a permanent program in 2021, enabling the state to provide unemployment insurance to undocumented workers whose wages pay into the state unemployment insurance and tax system but who were previously deprived of unemployment benefits. The identity verification system, managed by third-party cash platform AidKit, involves working with the Office of New Americans and the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment, and by proxy, their local partners. The process took seven to ten days in its initial phase, capturing an estimated five percent of Colorado’s total workforce that was left out of benefits, despite contributing an estimated $188 million to the state’s UI fund over a decade. Such efforts demonstrate states’ capacities to include non-ITIN households in public benefits.

Payment Frequency: Annual Lump-Sum vs. More Frequent

Some states have expressed interest in replicating the federal model of paying out the Child Tax Credit monthly, instead of making the traditional lump sum annual payment at tax time. More frequent payments have several potential benefits: they help recipients smooth consumption and match payments with the timing of regular expenses, as well as guarantee families some cash income throughout the year. Separating a CTC benefit from an overall tax refund can also make beneficiaries more aware that they are receiving a specific benefit for families with children. This is important, as almost half of recipients of the Earned Income Tax Credit report that they “have not used a government social program.”22 There are also arguments in favor of a lump-sum payment. Some families value tax refunds as a forced saving mechanism, and a lump-sum can enable large purchases that are otherwise out of reach. A full accounting of the pros and cons of more frequent payments is beyond the scope of this brief.

Regardless of the potential benefits of more frequent payments, moving away from a lump-sum distribution comes with significant new challenges. Most importantly, paying out a state CTC in installments rather than a lump sum may reduce recipients’ SNAP benefits. SNAP regulations clearly state that lump-sum refunds should not be counted as part of income when calculating benefits. However, the regulation is specific to “nonrecurring lump sum payment(s)”; it does not necessarily exclude tax refunds paid out on a more frequent basis.23 The specific regulation states that “Money received in the form of a nonrecurring lump-sum payment, including, but not limited to, income tax refunds, rebates, or credits.” States have some discretion in other income-setting rules, but are specifically prohibited from exempting “regular payments from a government source.” Unfortunately, the regulation is not an interpretation of a vague federal statue–it comes almost verbatim from the law that authorizes SNAP. However, that law specifically excludes counting income from “any payment made to the household under section 3507 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986,” which refers to the now defunct advance monthly payment system for the federal EITC. This shows that Congress did not necessarily intend for only lump-sum credit payments to not be counted as income. This arbitrary distinction–monthly payments simply change the timing of when tax refunds are received–is a potentially serious downside to more frequent payment methods.24 Washington DC is implementing a monthly payment system for its local EITC, and is asking the USDA for a waiver to allow it to not count these payments as income for SNAP. Even in the USDA rules that DC does not have to count monthly EITC payments for SNAP, the wording of the legislation authorizing SNAP may leave enough leeway that a future administration could reverse this ruling.

Other difficulties relate to implementation. A regular payments system will require a state tax agency to set up new infrastructure to allow recipients to update their payment information throughout the year. If set up as an advanced payment and is means tested, the credit will require strong protections so as to ensure that families are not required to pay back credits they are no longer eligible for, should their incomes increase or they move out of state.

While these issues present obstacles to administering a state CTC on a monthly basis, they are not serious enough to warrant forgoing setting up a monthly payment system altogether. For instance, even if families’ SNAP benefits are reduced, a system could be set up to replenish the losses with state funds. There is precedent for such a system in Alaska—which compensates for the reduction in SNAP from permanent fund payments.

States that do create a monthly payments system should also respect recipients’ preferences for payment frequency and allow families to opt to receive a lump-sum at tax time.25 If families bear any risk of having to repay the credit or having their SNAP benefits reduced, states should adopt an “opt-in” procedure, as a part of which families opting-in to these payments are informed about these risks.Evidence from the expanded CTC shows that while a plurality of parents preferred monthly payments, a significant fraction would have preferred a lump-sum payment.

Thus far, two states have the option of implementing CTC payments outside of the typical lump-sum refund at tax time. Minnesota’s legislation authorizes the commissioner of revenue to establish a system for administering advance payments, but does not compel it. Similarly, Oregon’s legislation only compels a quarterly payments system if the payments do not count against recipients’ SNAP allotments, via waiver, regulation, legislation, or other means. Oregon’s legislation prescribes that recipients must be able to opt-out of advanced payments, while Minnesota’s calls for the creation of an opt-in structure.

Unrestricted

One of the primary distinguishing features of cash assistance policy is that recipients may spend funds on what they determine their needs to be. This contrasts with most other safety net programs, particularly those targeting the poorest households. Policies like SNAP, WIC, and Housing Choice Vouchers provide income support for basic household needs like food and housing but offer limited benefit in the face of acute financial shocks or irregular incomes. SNAP and WIC can only be used on food—in fact, only on certain foods—and HCVs go directly to landlords.

The narrow income requirements, limited benefit amounts, and associated administrative burden of enrollment or continued eligibility verification are related ways these programs become highly restrictive. States also have discretion in administering SNAP and HCVs, sometimes adding restrictions to those programs. While the Earned Income Tax Credit (both federal and state versions) and TANF are more direct and unrestricted when received, their narrow income eligibility criteria limits each program’s ability to help families in most need. Benefits that phase in slowly with income can burden individuals with significant paperwork in exchange for limited financial gain—resulting in limited take-up across all eligible households, and neediest households in particular.

TANF has similarly limited takeup. Its narrow income criteria—as well as variation in criteria within each state—disincentivizes families from accessing the program. As just one example, in Texas, a single parent with one child may make a maximum income of $78 per month to receive a benefit of $136. To access that benefit, the parent must provide the state with documentation of present finances, “the value of things the family is paying for or owns,” and what the parent may pay for childcare or child support—on a recurring basis. These conditional and restrictive programs play an important role for some families, but direct cash assistance is notably preferable for the efficient delivery of flexible aid in times of acute need. Unrestricted cash aid was also a key feature of pandemic assistance programs when a national state of emergency made ease of access and use of aid a priority. However, household level emergencies or financial needs are often treated with steep stipulations for access within safety net programs.

In addition, unrestricted cash respects recipient preferences and what parents or guardians have expressed is most helpful. The Automatic Benefit to Children Coalition of over fifty policy research and child welfare advocacy organizations, including JFI, drafted a set of principles for cash support policies informed by a diverse parent advisory board of child tax credit recipients and potential recipients. These principles include an emphasis on no-strings-attached cash assistance. Unrestricted benefits delivery therefore reinforces recipient-centered program design, an increasing priority for many policymakers and research institutions beyond that coalition. Restrictions on use ultimately hamper the flexible role that cash assistance can uniquely play.

Financing

States have taken a variety of approaches to finance their CTCs. Broadly, they fall into three buckets: 1) progressive tax increases; 2) consolidating existing family benefits into a single, large CTC; 3) using an increase in state revenues to finance a CTC. The first two options are sustainable choices that can fund a CTC for years. The third option can work in some instances, but raises more concerns that a state will need to reduce a CTC or other state programs if revenue increases turn out to be temporary.

Colorado’s initial CTC provides a good example of financing via progressive taxation. The bill capped itemized deductions at $30,000 and $60,000 for taxpayers making more than $400,000 and limited deductions for business income for taxpayers making more than $500,000. Those provisions were expected to raise about $160 million dollars, more than paying for the cost of the CTC expansion, which was estimated to cost $107 million dollars.

Other states have pursued other specific tax increases.26 Other CTCs paired with tax increases passed as part of a broader budget agreement, where revenue raisers are not necessarily paired with specific spending provisions. It is beyond the scope of this brief to prescribe what specific strategies states should pursue. However, an important similarity across the country is that most state tax codes are regressive—higher income residents pay a lower share of their income to state taxes than low-income taxpayers. Even in states where wealthier residents pay more, they tend to only pay a bit more. For instance, in California, the state with the most progressive tax code, the top one percent of households by income pays less than two percentage points more than the bottom twenty percent.

For lawmakers interested in making their tax code more progressive, state CTCs can play an important role. Giving the lowest-income families the full value of the benefit helps offset the other taxes they pay. Lowering income tax rates on low earners will have little impact on progressivity, as most low income families already pay little to no income tax. However, low income families do pay sales taxes. Moreover, while they may be less likely to be property owners and pay property taxes directly, the incidence of property taxes is passed through via higher rental prices.27 Property tax assessment practices are also regressive, undervaluing higher value properties compared to lower-value properties. Because low-income families spend a large share of their income on rent and goods and services subject to sales taxes relative to higher-income groups, they end up paying a similar or higher share of their income to state and local taxes than high-income groups. Refundable credits like the CTC may be a more equitable option than trying to bake progressivity into the property and sales tax system.

States have options besides raising taxes to finance a CTC. Massachusetts and Minnesota provide good examples of consolidating existing benefits into one large CTC.28 The Niskanen Center’s State of Our Families report provides a comprehensive, fifty-state overview of potential consolidation opportunities for other states. Massachusetts’s pre-2021 tax code included a tax deduction for children under twelve. Deductions only benefit families with tax liability, however, which means they exclude the lowest-income families. Massachusetts replaced the deduction with a refundable tax credit, providing the same benefit as the old deduction system for high-income taxpayers, but newly including the lowest-income families.

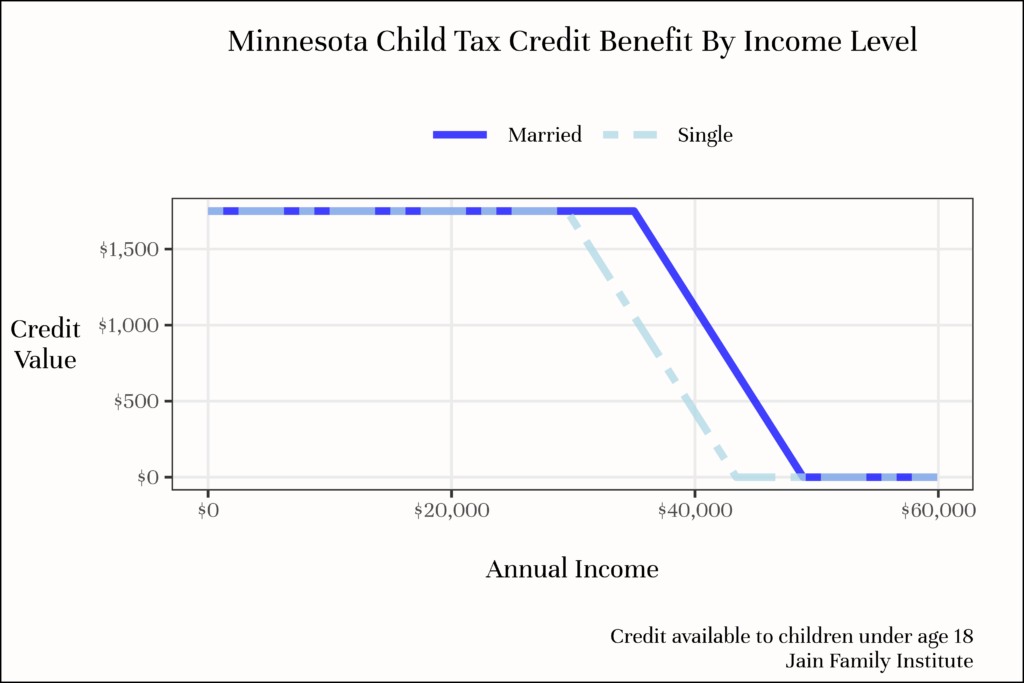

Minnesota’s benefit consolidation was more ambitious—it consolidated its EITC into one large CTC. The figure below illustrates the change: the solid dark blue line represents Minnesota new CTC benefit and the light-dotted blue line represents the state’s previous EITC (both for families with one eligible child). Families who previously benefited from the state EITC were not harmed—in fact, they received a much larger credit.29 Minnesota preserved the EITC benefit for families with no children and the family benefit for families who could claim older dependents for the purposes of the EITC. More importantly, the state CTC newly included the lowest-income families who were previously ineligible for the EITC. While the new CTC benefit was bigger, it would have been far more expensive (and likely not feasible) if it was not paired with EITC consolidation.30 The bill establishing the CTC was also funded via progressive tax increases; the means of financing a refundable CTC are not mutually exclusive.

Other states have financed state CTCs by increasing revenues. State budgets tend to grow over time, even without tax increases, due to economic growth. However, relying solely on growth can be dangerous because of natural year-to-year variation. New Mexico provides a cautionary example. The state is a hotbed of oil and gas activity, which is responsible for roughly a third of its revenue. These revenues sharply increased during the pandemic, which encouraged the legislature to pass a bonanza of tax cuts, including an expansion of the state’s CTC. While large enough to pay for these expansions at the time they passed, oil and gas revenues are very volatile in the long term. In fact, New Mexico’s state budget revenue is among the most volatile in the county, due to its reliance on oil and gas. There was a threat that the governor would veto the CTC in the name of fiscal sustainability, though eventually she let the expansion stand while vetoing other permanent tax cuts. All the same, the example points to the potential perils of counting on volatile revenue sources to fund a permanent program.

It’s particularly important to sustainably fund a means-tested state CTC because they are counter-cyclical. When the economy is doing well, fewer families will qualify; jobs are easier to come by and wages are growing. State budgets tend to grow over time without raising taxes due to economic growth. However, during a recession when the unemployment rate is higher, more families will qualify, making the CTC more expensive.31This could be offset in the medium term by declining birth rates, particularly for CTCs targeted for children under six. It’s good to provide more support to families and stimulate the economy during a recession, but it creates challenges for state budgets, which will also be making less revenue due in this period. States that rely on more stable revenue sources and invest surpluses into rainy-day funds will be better prepared to meet the challenge of funding a CTC during a recession.

Increasing Benefit Take-up

Families with low or no earned income are eligible for refundable state CTCs. This gives the credit unique poverty-fighting power and ensures tax benefits can reach the most disadvantaged children. However, eligibility does not automatically ensure that families actually receive benefits. Tax filing can be a complicated, intimidating process, and many low income families are not required to file a return even if they earned income. Takeup problems have long plagued the Earned Income Tax Credit: the IRS and Census Bureau estimate that one in five eligible families do not receive it. Full participation in state CTCs will be even more challenging because families with no taxable income are eligible for a credit. Families with no earned income normally have no obligation or reason to file a tax return because they would receive no tax benefit and have no tax liability.

States that pass fully refundable child tax credits should pair them with a plan to ensure all eligible children receive the benefits they are entitled to. Thus far, no state has paired a CTC expansion with serious reforms aimed at ensuring complete takeup. Making $0 income families eligible for a state CTC without proactive actions to ensure eligible families get the benefit will all but ensure low takeup.

States can take several proactive measures to increase benefit enrollment. The first, lowest-effort class of actions would aim at increasing awareness of the benefit and encouraging families to file. While such interventions have shown very little success at increasing uptake for the Earned Income Tax Credit, they may have more success for the Child Tax Credit because low- or no-income families may not be aware they are entitled to a large benefit. Families who do not file taxes, despite EITC eligibility, likely know about the credit but find tax filing too complicated or do not file for other reasons. However, the calculus may differ for families with no earned income eligible for a state-level CTC. These families are not ordinarily eligible for any tax benefits and have no obligation or reason to file. They are unlikely to file a state tax return unless informed of their eligibility for the benefit. Moreover, while the EITC has been around for almost fifty years, fully refundable child tax credits that benefit families without earned income have only been implemented in the last few years. For these reasons, outreach campaigns are likely to have some success in increasing tax filing and credit takeup.32 Some states have passed laws that mandate employers provide their employees a notice about the EITC at tax time along with their W-2. Unfortunately, research has shown that these notifications do not significantly increase EITC takeup, which is consistent with other research showing limited success of other “awareness” interventions for the EITC. States with pre-existing notification laws could modify them so employers also include information about state CTCs. However, employer notifications are poorly targeted for families with no income from work, who are the population most at risk of missing out on state CTC benefits and in need of information.

The most effective way a state can increase awareness of the credit is by using data from enrollment in other state-administered safety net programs. Specifically, SNAP and Medicaid/CHIP are wide-reaching programs that include parents and caregivers with low or no earned income. States should use a mix of mailers, text messages, and in-person communication to inform participants about their likely eligibility for the CTC.

Second, states can try to make filing taxes for the lowest-income families easier. Regular tax filing can be intimidatingly complex. Most people use paid tax preparers that erode the value of any refund, while others are dissuaded from trying to file at all. However, most of the complicated factors involved in filing taxes are only relevant to those with substantial incomes.

States should explore following the example of the Federal government which, during the pandemic, created simplified filing portals to ease the tax filing process for low-income families. These portals would be available to anyone with an income below the threshold that requires tax filing and would not require detailed income verification beyond self-attestation. They would only require families to answer questions relevant to receiving the state-level CTC, which greatly simplifies the filing process.33 By eliminating the need to verify income information, non-filer portals erode a justification for universal child benefit. While a means-tested benefit with a nonfiler portal still requires moderate-income families to submit income verification, these families already have a filing obligation, and should be encouraged to file to receive other income-tested benefits.

A state-level simplified filing portal comes with an important tradeoff—it would not allow families to claim any potential state EITC or receive a refund based on excess withholding, as that would require a full tax return.34 This is a far less important concern if states consolidate their EITC benefit into a larger CTC, like Minnesota. This should not dissuade states from setting up simplified portals. First, families with very low incomes would have little benefit from a state EITC and any extra withholdings. Second, when Code for America implemented an option to file a full return and receive the federal EITC in their simplified portal, just 0.2 percent of families successfully did so. A simplified filing portal with screening tools and language directing users to other free “full filing” options if they have significant earnings should be more than enough to deter families who could be missing out on significant benefits.

Third, states should try to automatically give the benefit to eligible families. This would remove the burden of signing up families and is therefore the most effective way to get tax benefits to as many eligible families as possible. Automatic payment is also far easier to facilitate at the state level than the federal level, because most safety net programs reaching low-income families are administered at the state level. As such, states can modify credit-claiming rules to accommodate automatic payments. However, there are a number of tricky administrative issues that are beyond the scope of this report.

Facilitating automatic payments will require interfacing with data from other safety net benefits–SNAP and Medicaid/CHIP are the most widely used and likely to contain eligible families. States with high income phaseout points should find this easier—any family enrolled in a safety net benefit should be income eligible. This provides a stark contrast to the design of the EITC, where the benefit depends on your precise income. Because safety net benefits do not have the exact same income information as a tax return, it is far more difficult to automatically pay EITC benefits. States that phase out their CTCs at lower income points where families may be eligible for safety net benefits but not the CTC will need to reference a safety-net program’s income data, perhaps only focusing on families with very low or no reported income.

One way to avoid paying out a CTC to families above the point of income eligibility is to wait until after the tax filing deadline. Higher-income families are required to file taxes and could easily be excluded. Families who appear in safety net program data but don’t appear in any filed tax returns are unlikely to have an income above the phase-out point. If a state automatically pays families before tax time, based on data from other programs, it can use SSNs and ITINs of children claimed on a return to avoid double payments.

Politics of State-Level Child Tax Credit Expansions

At the federal level, support for the expanded CTC has been mixed and fairly partisan. The initial CTC expansion passed narrowly on partisan lines as part of the American Rescue Plan Act. Negotiations suggested that all but one Democrat in Congress supported the credit’s renewal. However, on the Republican side, most representatives appeared to oppose the credit. While there may be some federal Republican support for making the existing credit larger, only Senator Mitt Romney has shown any public support for making a credit available to families without taxable income.

Comparatively, support for state-level child tax credits has been less divisive and more bipartisan. Almost all states that have passed state-level credits have done so with wide majorities. In the sixteen votes in states that recently enacted or expanded a credit that we were able to track down votes for, the CTC was supported by 81 percent of State Senators and 78 percent of State Representatives.35 We are missing Massachusetts’ original CTC vote and New York’s original 2006 vote for its Empire State Child Tax Credit. The three least-supported state CTCs (in New York, Massachusetts, and Minnesota) were passed as part of broader budget agreements that contained other controversial measures.

While all the states that have passed a credit have a solid Democratic lean, many votes on the bills establishing the credits have had bipartisan support. For every state that passed a refundable CTC where we could find the final votes in the legislature, we compared the CTC votes with the partisan composition of the state house. We conservatively assumed all Democrats and Independents voted for passage and then examined what percentage of Republicans must have voted for its passage to explain the final vote, counting abstentions as not supporting. Overall, an average of 40 percent of Republican State Senators and 30 percent of Republican State Representatives voted in favor of fully refundable child tax credits.

In states where the CTC got few Republican votes, it wasn’t necessarily that Republicans were against the credit. For instance, in Minnesota, the Republican State Senate Minority Leader Mark Johnson said, “I can agree with the child tax credit idea,” but opposed other tax credits passed as part of the same package. In Maryland, Republicans appeared to specifically oppose expanding the credit to ITIN holders, proposing an amendment restricting the credit to legal residents that failed along partisan lines. In New Jersey, Republicans put forward a (failed) amendment expanding the credit’s age eligibility.

There is also some evidence of interest in refundable CTCs in Republican-controlled states. Most notably, Montana’s Republican Governor Greg Gianforte championed a $1,200 child tax credit for children under six. The original text of the bill (introduced by Republican legislator Joshua Kassmier) made the credit fully refundable with no minimum income requirement. In committee, it was amended to require “proof of earned income,” an unfortunate change, but still far preferable to the status-quo Federal CTC, which only allows parents with incomes upwards of $25,000/year to claim the full value of the credit.36 California’s Young Child Tax credit had the same earned income requirement until 2022. While the bill died as part of a broader squabbling over budget priorities, it is still indicative of some bipartisan state-level support for a more inclusive Child Tax Credit.

Expanding State CTCs

Some state CTCs provide a relatively modest benefit. However, once a state passes a CTC, it becomes a platform for future expansions. Of the eleven states with a refundable child tax credit, six have already raised the benefit amount or broadened eligibility.

While state CTCs have only a short track record, state EITCs provide a similar history of expansion. Based on historical data on the EITC, we estimate that state EITCs have a 21% chance of expansion after they are first passed, and just a 3% chance of being restricted or reduced. In other words, once a state has a refundable EITC, it expands it on average once every five years, and has a six times higher chance of expanding the benefit than making it smaller.37 This draws on historic EITC expansion data from The Upenn Wharton Budget Model.

This year, several states introduced fully refundable child tax credits or expansions that did not pass, including Hawaii and Virginia. Last year, a Republican legislator in West Virginia also introduced a fully refundable CTC eligible to households with no reported income, but the measure was not supported by other members of the Republican majority.

Other states passed non-refundable child tax credits: Utah introduced a $1,000 per child CTC that reduces taxes owed but is not refundable. Illinois also passed a nonrefundable credit of $100 per child (for parents with incomes under $60,000). Other refundable and nonrefundable credits target childcare expenses explicitly. While these efforts show an interest in supporting families, they cannot play the same role as refundable benefits in poverty reduction, particularly for families who may already have little to no income tax liability. Non-refundable benefits should be converted to fully refundable cash assistance if they are meant to provide financial buffers for material hardship or address acute cash needs.

Some advocates aim to use refundable earned income tax credits (EITCs) as a basis for progress toward refundable child tax credits. However, EITCs differ substantially in design, as CTCs fill a gap in other means tested benefits by providing income support for households with little to no reported income. EITCs are often based on a percentage of federal EITC benefits or follow the same eligibility criteria, which presently requires a minimum $2,500 income to begin to receive the full benefit. However, efforts to consolidate EITC-type benefits into a more inclusive and fully refundable child tax credit (at $0 income) can increase the poverty impacts of such programs while ensuring flexible cash assistance reaches households in greatest need.

Conclusions & Further Considerations

The rapid rise of refundable state CTCs shows the continued resonance of providing a guaranteed income for families, even as the expanded CTC faces headwinds at the federal level. Eleven states now guarantee families with young children a minimal level of income. While no state comes close to matching the size of the expired federal program, many states offer substantial sums—over half have a maximum benefit of at least $1,000. And even the short history of state CTCs shows these benefits tend to be expanded: of the eleven states with a refundable CTC, six have already expanded them.

Refundable state CTCs offer a unique instance of states following the example of the federal government, rather than the federal government adopting policy innovations at the state level. While the federal CTC expansion only lasted six months, it was enough to cause a huge drop in child poverty and substantial reductions in material hardship. State lawmakers and advocates took note: all refundable state CTCs that gave the maximum benefit to families with no income from work were passed in 2021 or later.

While state CTCs help provide a guaranteed income for families, they perpetuate the exclusion of other adults without children from the cash safety net. “Able-bodied adults without dependents” (ABWDs) are by and large not eligible for the work-contained cash safety net that families with children are: they are not eligible for TANF or the CTC, and they receive at most $600 from the federal EITC at a very narrow income range. By and large, states do little to fill this gap. The most generous state, Maryland, simply matches the Federal EITC for childless workers.38Washington DC has the same policy.

There are good reasons to focus efforts on families with children: they have a higher poverty rate, and there is a strong research base showing investments in childhood pay off in the long run via improved adult outcomes. Child benefits are also more popular and politically feasible—ABWDs are not a particularly sympathetic group. However, states should consider measures that provide a more inclusive cash safety net that covers households without children.

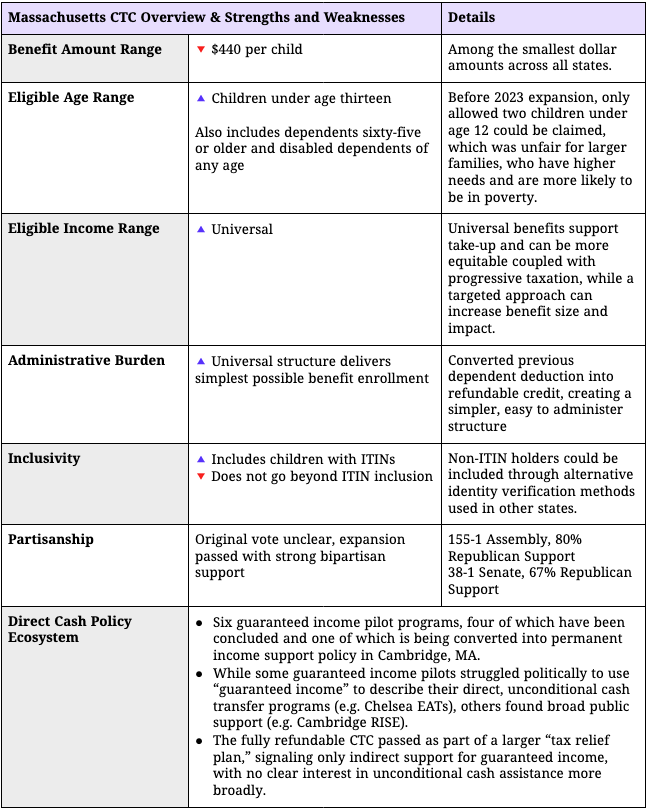

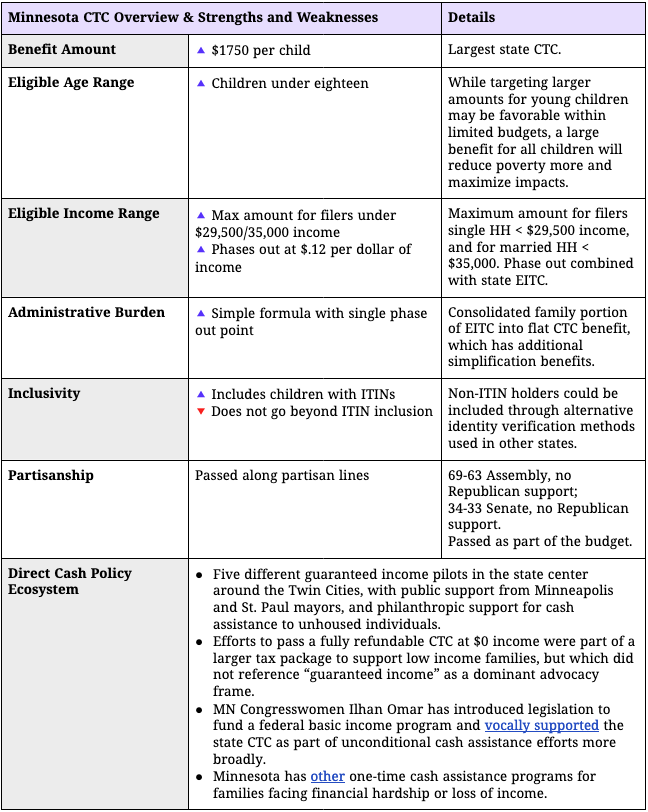

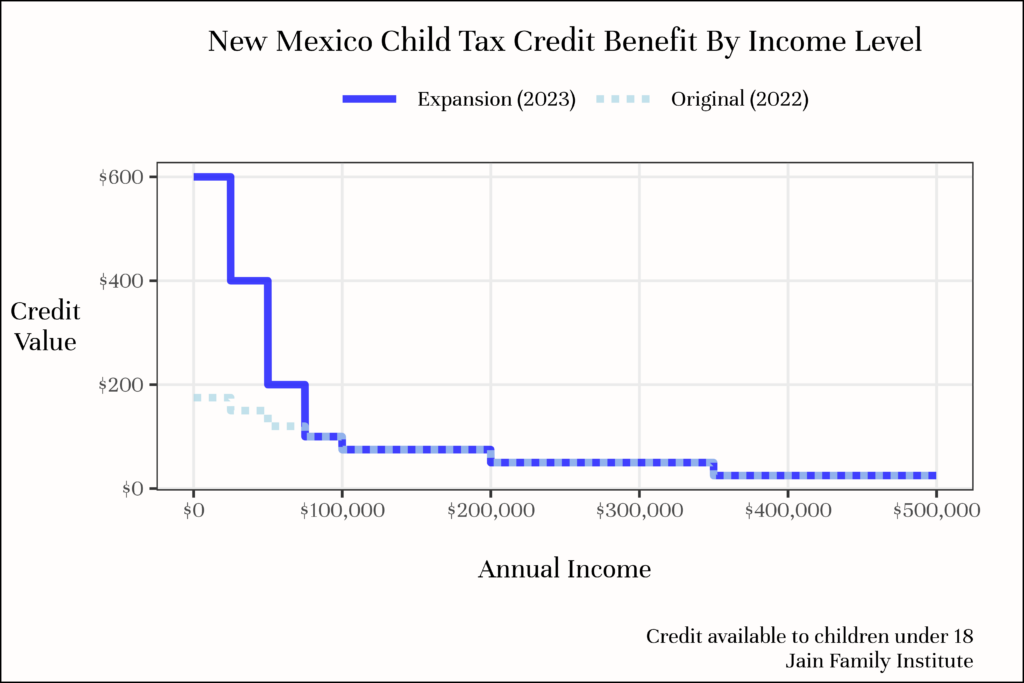

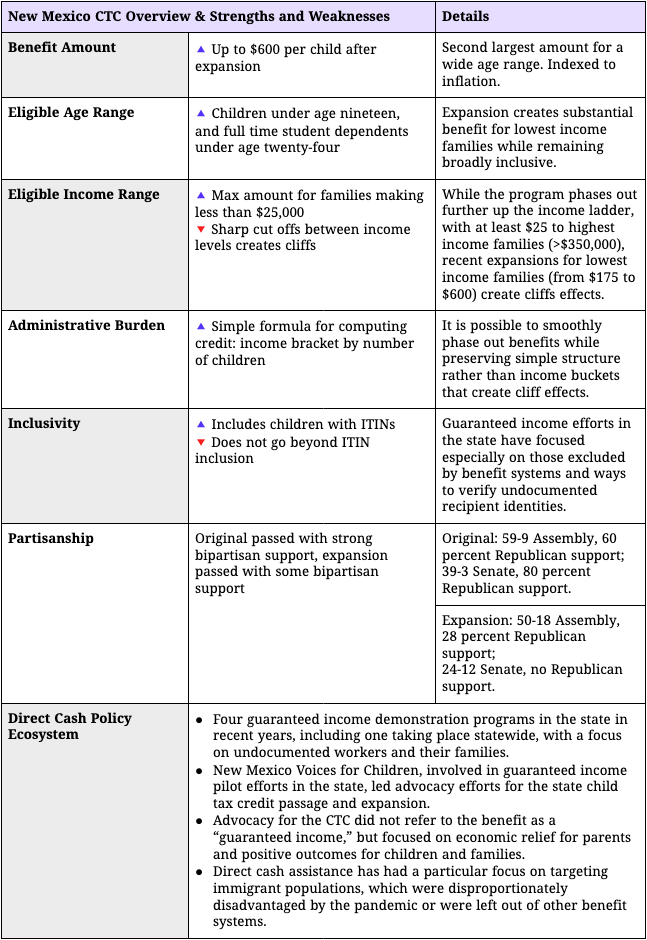

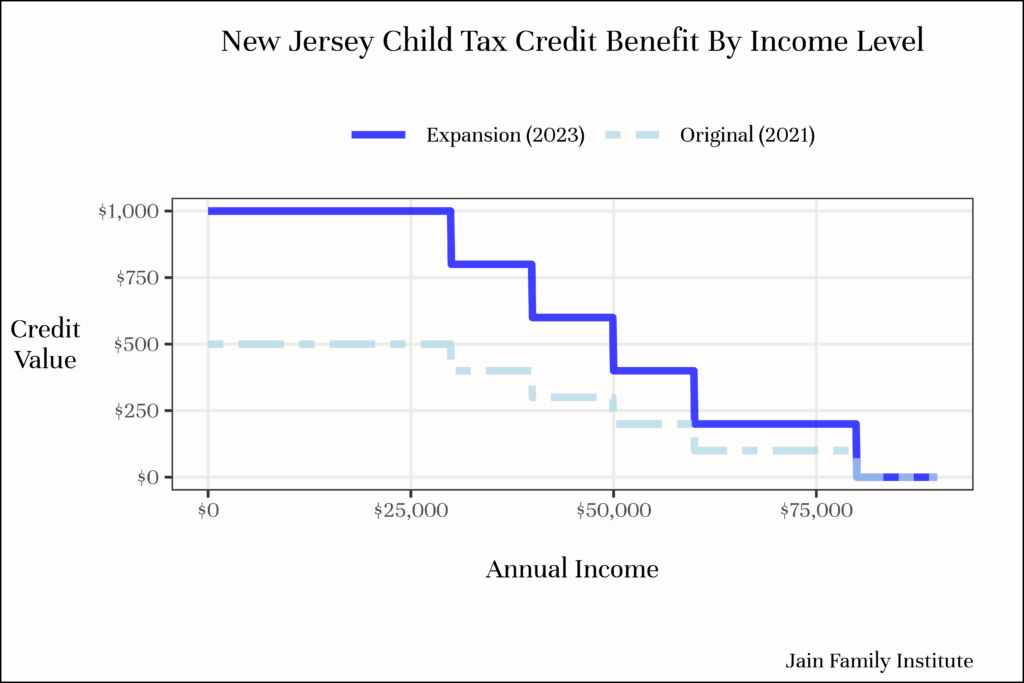

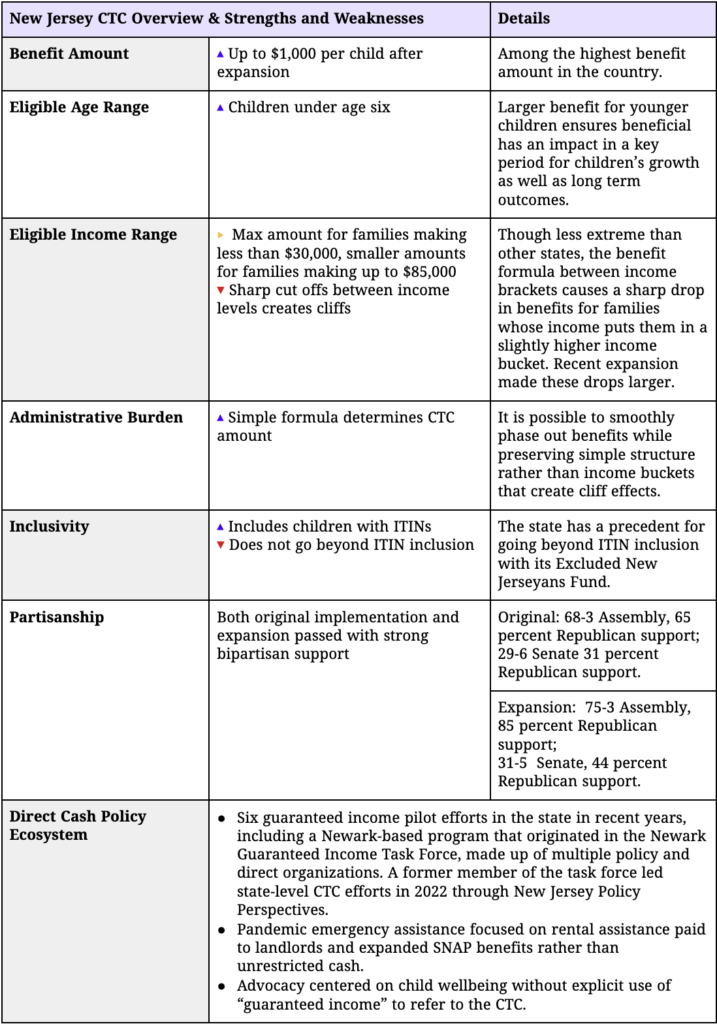

Comparing All State CTCs

Below we provide state-by-state details on the child tax credit programs summarized above. Each table overviews topline details and analyzes the strengths or weaknesses of the programs. We also note opportunities or models the state may have to improve their CTC programs. While we are not prescriptive about all cash transfer parameters, we note strengths and weaknesses, based on evidence described in the analysis above. In the case of age eligibility, we note that targeting young children with larger benefits is a strength relative to other programs but not in an absolute sense. Helping a greater number of children would of course increase the program’s impact. But within limited budgets, we focus on the larger benefits to young children in lowest income (or no income) households. See the discussion above for more analysis of this policy choice. In addition, the “direct cash ecosystems” described below are not a complete picture of all guaranteed income activity in the state. Similarly we provide only a high level description of how these policies passed. The tables offer a simplified picture of public initiatives for cash assistance and discourse we have encountered, as researchers in conversation with guaranteed income pilots and advocates for various forms of direct cash assistance—through the tax system or otherwise.

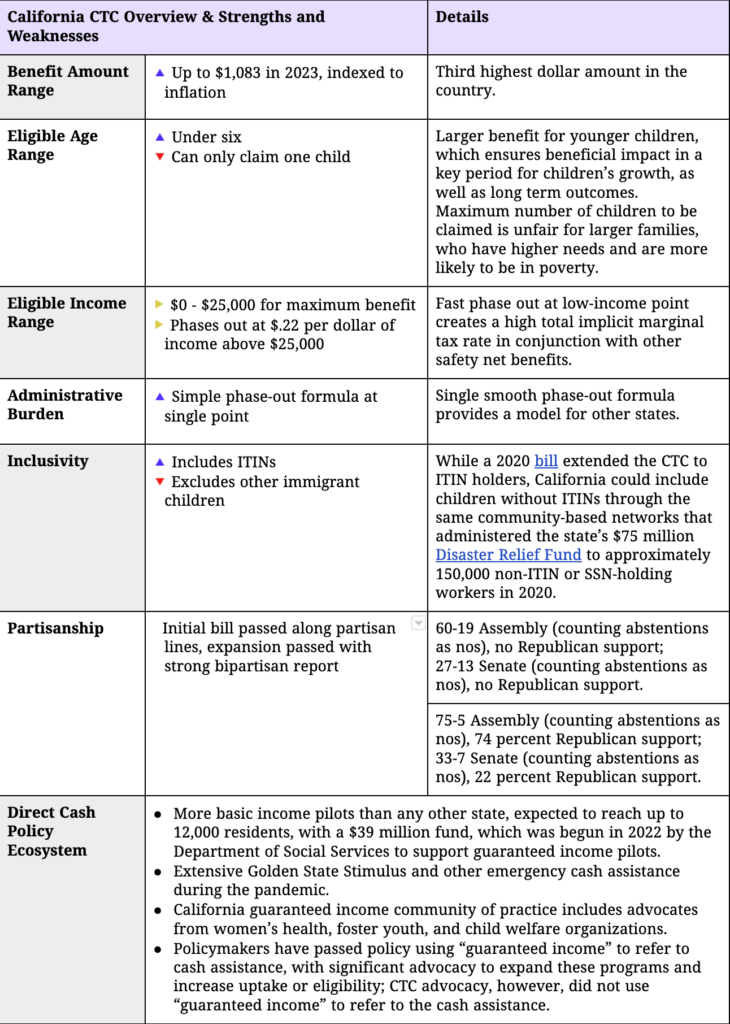

California

California has had its Young Child Tax Credit since 2019, but in 2021 it eliminated an earned income requirement, allowing parents with no reported income to access the benefit for children under six years old. While the state has more guaranteed income programs, policy, and advocacy than any other state, efforts to expand the CTC and make it refundable at $0 income were overwhelmingly about child poverty and wellbeing, and not centrally using the term “guaranteed income.” The program provides the third highest CTC benefit in the country, targeting young children and providing the largest benefit at no income, with a single phase-out starting at $30,000.

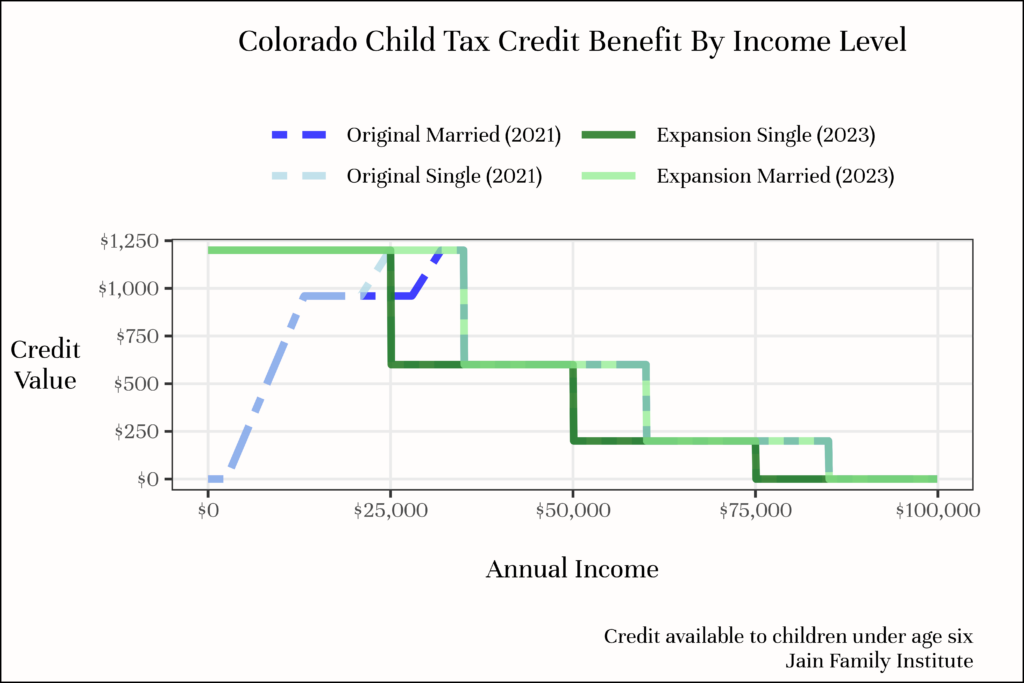

Colorado

In 2023, Colorado became the state with the second largest child tax credit, while expanding the credit to ensure families with no income could receive the full benefit: up to $1,200 per child under the age of six. While the Colorado legislature is majority Democratic, the expansion of the state CTC passed with strong bipartisan support as a measure to make the tax system more equitable and redistribute tax revenues directly to Colorado families in need. The state CTC is set to reach 195,000 eligible children, with roughly 65,000 children in households with under $25,000 or $35,000, for single or joint filers respectively, receiving the full $1,200 per child. The full benefit structure is explained in the figure below.

Refund Structure of the Colorado Child Tax Credit

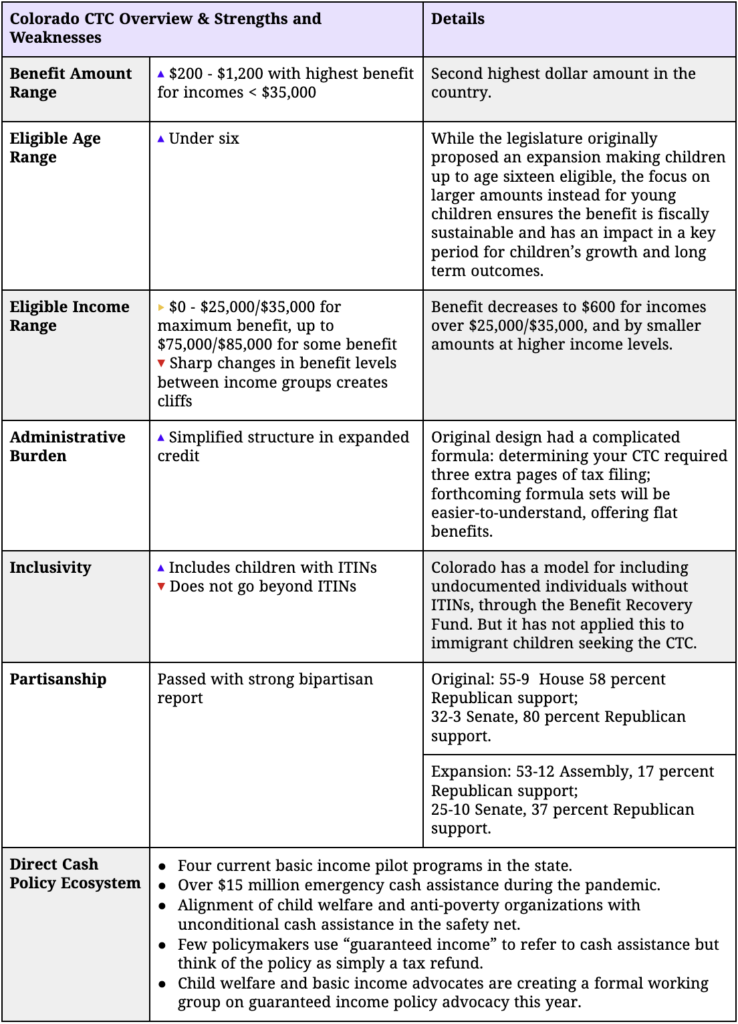

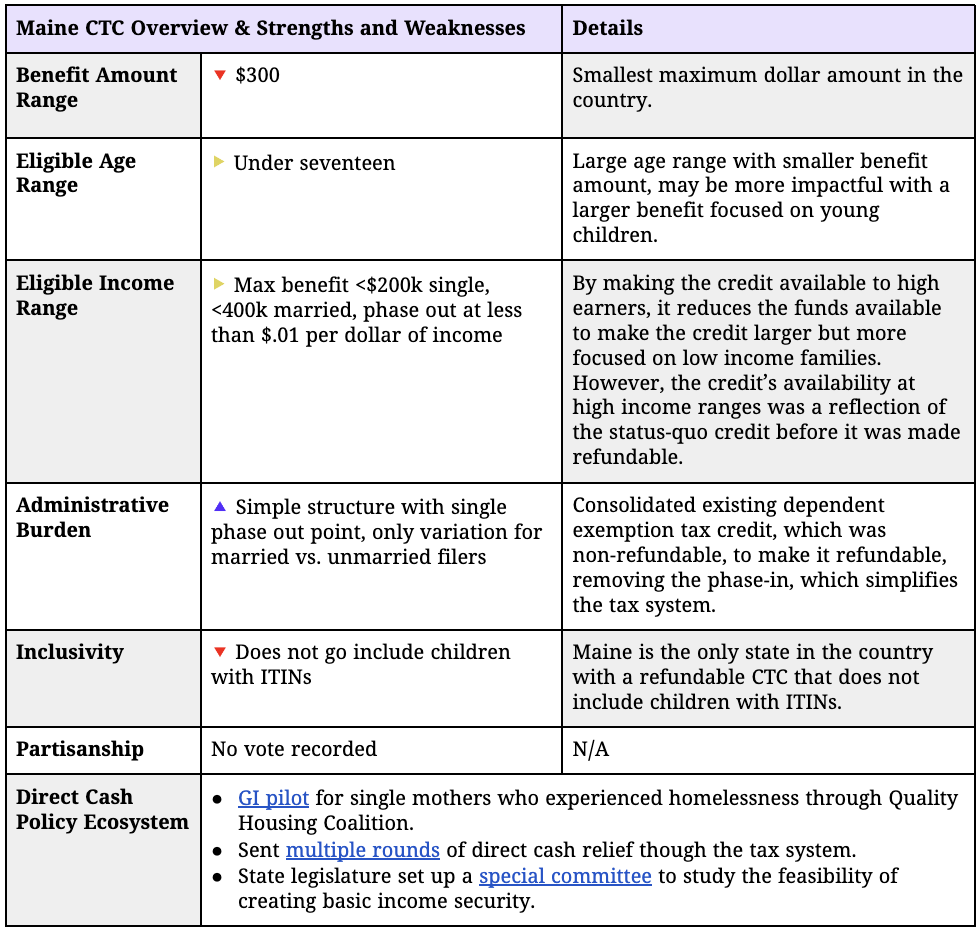

Maine

Maine’s CTC was signed into law July 11, 2023. Rather than creating a new program from scratch, Maine made its existing dependent exemption tax credit fully refundable. It was supported by the Maine Economic Policy Center, the Maine Associated for the Education of Young Children, the Maine Children’s Alliance, the Maine Council of Churches, and Maine People’s Alliance, among many others. Unfortunately, unlike every other state that has adopted a CTC, it did not expand the credit to include children with ITIN numbers.

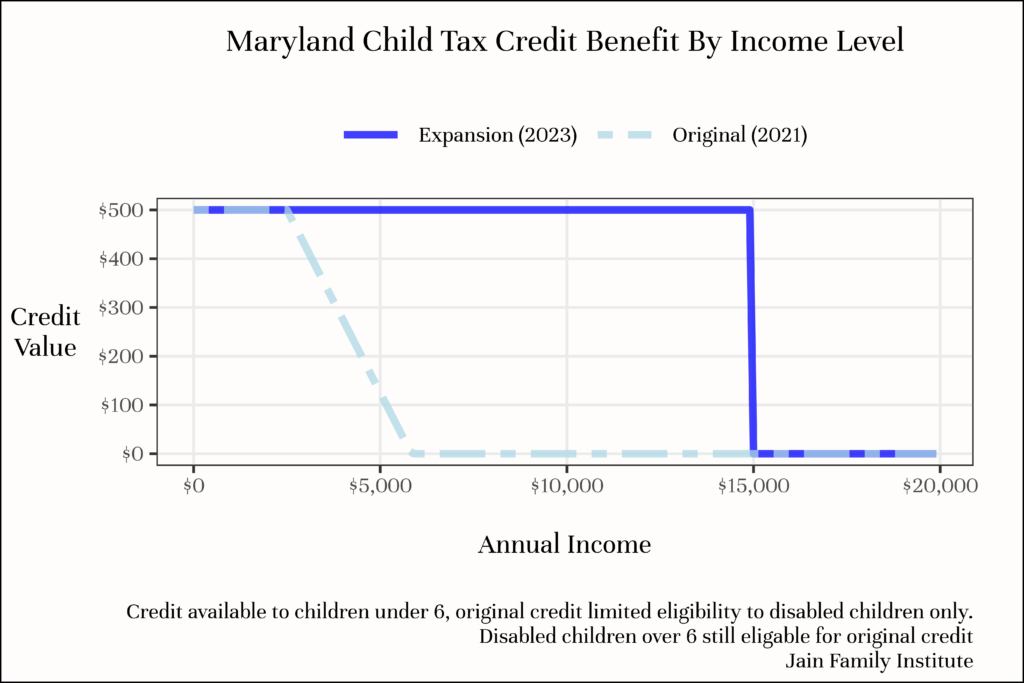

Maryland

Maryland initially passed its Child Tax Credit in 2021. Part of a larger package that expanded the EITC, the CTC component was very small. It was worth just $500, and limited eligibility to disabled children whose parents had an income less than $6,000. One positive part of the design is that it very explicitly gave low-income parents a benefit where the federal CTC did not—the benefit phased out as the federal CTC phased in. In 2023, the legislature returned to the CTC, expanding the benefit to all children under age six rather than just disabled children, and extended the income eligibility to under $15,000. It remains among the smallest and most targeted CTCs in the country, but is far more substantial than the initial credit.

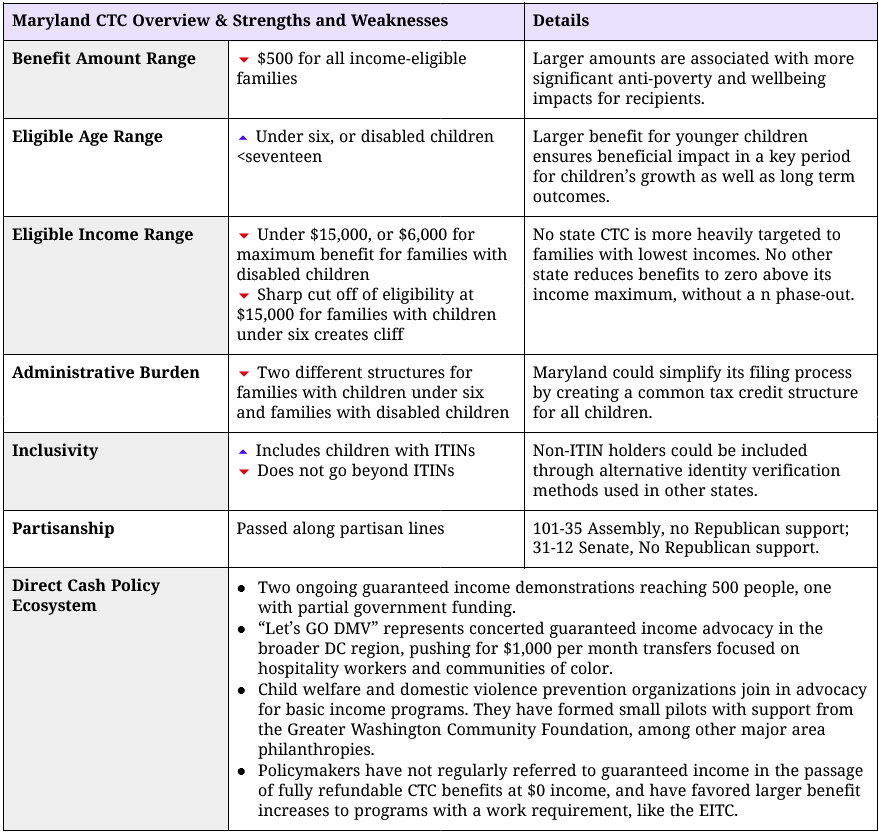

Massachusetts

Massachusetts’s CTC was a result of benefit consolidation. Massachusetts’s pre-2021 tax code included a tax deduction for children under twelve. Deductions only benefit families with tax liability, however, which means they exclude the lowest-income families. Massachusetts replaced the deduction with a refundable tax credit, providing the same benefit as the old deduction system for high-income taxpayers, but newly including the lowest-income families. It is the only credit that is provided universally, regardless of income. In 2023, the credit was increased to $440 per eligible child (initially $310), no longer capped the total number of children families could claim, and made twelve-year olds eligible.

Minnesota

The Minnesota CTC passed as part of a larger 2023 tax bill that both increased state revenues and came with an array of other tax reductions for lower-income households. The CTC was one way to defer the benefits of proposed tax cuts onto low income households when lawmakers originally sought to eliminate all income taxes on social security insurance beneficiaries, including many high-income recipients. Instead, advocates argued for low-income moms who could do more with a refundable tax credit than wealthy retirees. The larger tax package then passed with various reforms that redirected tax revenues to lower-income households, making the tax code broadly more progressive. The state CTC was celebrated in particular for its potential to reduce child poverty in the state by roughly a third. “Guaranteed income” was not a primary descriptor for this CTC push among legislators or advocates, but Minnesota Congresswoman Ilhan Omar published a local op-ed calling for the credit and positioning the move within her concerted efforts to support guaranteed income and cash transfers at the national level. The Minnesota CTC is now the largest in the country.

New Mexico

New Mexico passed its child tax credit in 2022 and expanded amounts in 2023. Efforts to introduce and pass the legislation were part of omnibus tax bills in 2022 and 2023, bolstered by advocacy and policy analysis from New Mexico Voices for Children. The focus of the tax reform was to benefit over 300,000 low income children and improve maternal and child wellbeing: from decreasing child poverty to improving mental health. Guaranteed income was not an explicit part of the advocacy campaigns. Cash pilot efforts have not been a large part of advocacy, although some members of New Mexico Voices for Children talked about their tax credit cash assistance work later in 2022 at a “guaranteed income now” conference.

New Jersey