Policy Insights: ‘Legislating Relief’ – expert perspectives on higher education bills

On August 7th, JFI hosted leading research and policy experts on higher education finance and debt to discuss the pandemic’s impact on student debt burdens and the proposed legislative responses to that crisis. The event, recorded here, first summarized key insights from research on higher education debt, including JFI’s Millennial Student Debt Project, followed by a focus on policy responses relative to that research. Below is a summary and transcript of the key insights raised. Experts from JFI, The Century Foundation, the Center for American Progress, the Roosevelt Institute, Education Trust, Student Borrower Protection Center and the National Consumer Law Center discussed key components of House and Senate bills such as CCCERA, S.4141, the HEALS Act, and the HEROES Act. These bills would legislate continued student debt repayment relief that is set to expire at the end of September as mandated by the CARES Act’s limited pandemic repayment pause. Shortly following the event, the White House released an executive order extending debt relief through the end of 2020, but advocates and experts point out that the need for legislative relief continues, as upwards of 9 million student borrowers will not benefit from the executive order and higher education institutions as well as states face dramatic revenue shortfalls that can negatively impact students. The key points addressed below remain pertinent to inform that policy debate.

Speaking to the research were:

- Laura Beamer, Lead Researcher on Higher Education Finance at JFI

- Marshall Steinbaum, JFI Senior Fellow and Assistant Professor at the University of Utah

- Julie Margetta Morgan, VP of Higher Education Research at the Roosevelt Institute

- Dr. Jalil Bishop, Vice-Provost Postdoctoral Scholar in Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania and principal investigator for the Education Trust’s upcoming study on Black student debt.

Policy experts analyzed federal proposals for higher education relief:

- Ben Miller, VP for Postsecondary Ed at Center for American Progress

- Jennifer Mishory, Sr. Fellow at the Century Foundation

- Mike Pierce, Policy Director at the Student Borrower Protection Center

- Persis Yu, Director of the National Consumer Law Center’s Student Loan Borrower Assistance Project

Research Insights

Laura Beamer framed JFI’s Millennial Student Debt (MSD) project as an investigation of inequities in access.

- The first two publications focused on geographic access, using zip code level data to calculate school concentration and average net price for each zip. JFI researchers found that access has become more geographically unequal since 2008, with residents of poorer zip codes having significantly less access. (Explore the map and most recent analysis.)

- JFI’s upcoming publication will focus primarily on financial access, utilizing individual-level credit bureau data that breaks down student debt statistics by zip code.

The pandemic has also drawn attention to the importance of broadband access. Online education cannot solve geographic access, as broadband and geographic access are positively correlated.

Marshall Steinbaum situated the MSD research within the current higher ed landscape, explaining the inequitable effects of the Great Recession and the likely exacerbation of the debt crisis with the current crisis.

- Due to state cuts to higher education during the Great Recession, traditional institutions began adopting for-profit like business models, and financial aid policies grew less egalitarian.

- With the ongoing crisis, higher education has already made key decisions that will likely lead to similar exacerbations of the debt crisis: poor conduct in opening during the pandemic, and state budget austerity measures including cuts to higher education.

He also pointed to a 2018 paper, coauthored with Julie Margetta Morgan, on the credentialization dynamic. Due to a poor labor market, the cost of obtaining credentials and job training has slowly shifted from employers to workers. The current crisis will likely exacerbate this dynamic.

Julie Margetta Morgan interrogated three long-influential assumptions about the student debt program that have been shown to be false.

- It was assumed that student loans would be primarily for middle income students. → Lower income students are increasingly relying on loans, rather than government grants, to finance their education.

- It was assumed that student loans would lead to more education and thus more earnings in the labor market. → Despite huge increases in student debt and modest increases in levels of education, earnings distributions have not changed.

- It was assumed that student loans were race neutral. → Black borrowers fare far worse in the student loan program than their white counterparts.

She also argued that the higher education response to the Covid-19 crisis ignores most of the lessons learned from the Great Recession. Budget cuts and short-term relief will again lead to increased debt, which will have a disproportionate impact on Black borrowers. See her work on regulation of for-profit colleges here.

Dr. Jalil Bishop focused on his research interviewing Black borrowers, bringing attention to three themes he saw repeated by many interviewees. (See some of his writing here.)

- Black borrowers experienced student debt as a lifetime sentence, or as something inevitable and necessary to attain the education needed to earn a living wage.

- Student debt is generational. Many Black student borrowers’ parents also have student loan debt.

- Debt interlocks with other debt. Student loan burdens feed into other forms of debt like credit card debt and payday loans.

Hearing from Black borrowers is part of the greater need to start discussing anti-racist solutions to the student debt crisis. Rather than using data from Black borrowers as a mere attention-drawing technique, or assuming that Black borrowers’ concerns will be addressed through universal or class-based solutions, it’s necessary to incorporate perspectives from outside of research and policy professionals to further an active dialogue about anti-racist solutions. The Education Trust is soliciting participants for a nationwide study of Black student debt here.

Policy Insights

Jennifer Mishory laid out a three-part framework for policy solutions, arguing broadly for solutions that relieve immediate financial distress, address the inequality exacerbated by the pandemic, and pave the way for a robust and equitable recovery. Applying this framework, Mishory reiterated the necessity of long term investment in public higher education. The HEROES Act would rely on direct-to-state funding, whereas the Senate Democratic Proposal would rely on both direct-to-state and direct-to-institution funding. But more importantly, Mishory emphasized that with either type of funding, the details matter. For example, policymakers must carefully examine maintenance of effort provisions—like the one included in the HEROES Act—and automatic stabilizer provisions. Accounting for these details is part of the larger need to create a conversation of accountability, so that the predatory practices that proliferated during the Great Recession do not grow any further. Mishory ended by encouraging higher education to look at bigger-picture relief efforts, like unemployment insurance reforms, that also affect students, and criticized the Senate Republican proposal that would roll back unemployment insurance for students. See her analysis of the HEROES Act here, and detailed report on the racial wealth gap in student debt.

Ben Miller argued that the pandemic and economic downturn require that higher education relief contains three components: debt relief, money for colleges, and money for states. On the funding allocation under the CARES Act, Miller named two major policy choices that had negative repercussions—first, the choice to differentiate between part-time and full-time students when allocating funding; and second, the choice to allocate funding equally among all colleges, resulting in direct institutional support of for-profits. Going forward, Miller advocated strongly for allocating funding based on head count rather than part-time vs. full-time status, which would increase aid to community colleges. He also condemned the decision to allocate any funding to for-profits, and recommended relegating for-profits to the side, as has been done in legislative proposals following the CARES Act, such as the HEROES Act and the HEALS Act. Looking toward the future, Miller called for a robust debt cancellation policy, which was not included in the CARES Act. From the current proposals, he argued that up-front debt cancellation, as proposed in the HEROES Act and in Senator Murray’s proposals, was preferable to cancellation along the way. See his analysis of the CARES Act here, and better formulas for implementing education relief here.

Mike Pierce continued Ben Miller’s analysis of the CARES Act, reiterating the merits of the universal payment pause as opposed to a targeted approach. Given the slow responsiveness of the student loan system, policy that would require opting-in, like the proposal from Senator Alexander, would work very poorly. Like Miller, Pierce called for more ambitious, broad based proposals for enduring student debt cancellation. He addressed the potential difficulties in operationalizing targeted schemes like the one proposed in the HEROES Act, and criticized Senator Alexander’s proposal, now one of the provisions in the HEALS Act, for taking another step back from cancellation proposals like the HEROES Act. To illustrate the potential effects of a universal student debt cancellation scheme, he explained that cancelling just $10,000 would pull around a third of borrowers out of the student debt system, then better equipping the system to serve everyone else. See SBPC’s most recent work on “shadow student debt” here.

Persis Yu highlighted her work with the Student Loan Borrower Assistance Project on the negative impact of seizing borrowers’ wages and tax benefits during the pandemic, pointing to a recent report that found that borrowers whose EITCs were seized faced increased rates of housing instability. Although the CARES Act was supposed to cease collection efforts in March, implementation within the broken student loan system has been rocky, and borrowers fear the upcoming restarting of collection efforts on October 1. Yu also added to Pierce’s criticisms of the HEALS Act, as it would provide no relief for defaulted student loan borrowers, who are some of the most vulnerable borrowers. She emphasized that vulnerable borrowers had faced continuous obstacles within the loan system prior to the pandemic, arguing that a solution for the current crisis would require not only triage, but long-term recovery—for example, policy to instate a statute of limitations so that debt does not follow borrowers, particularly borrowers in default, for their entire lives. See NCLC’s recent memo on critical protections for the next relief package.

Below is a condensed, edited transcript of their discussion. A recording of the full panel can be found here.

Research Perspectives

Laura Beamer:

The Millennial Student Debt project is a research project investigating financial, workforce, and geospatial behaviour of millennials with student debt. By analyzing student debt, we want to examine the inequities in access that lead to disparate outcomes.

Our first two MSD publications focused on geographic access. We looked at data from every zip code in the US and US territories in order to ascertain the relationship between geographic access, zip code-level demographic attributes, and different higher education costs.

- To measure geographic access, we used IPEDS and ACS data to pinpoint higher ed institutions across the country and establish driving distances around them. For every zip code, we compiled a list of institutions considered geographically accessible, and gathered corresponding information on the accessibility of those institutions, based on the type of institution, enrollment numbers, sticker price, and net cost.

- We then made two key calculations to streamline analysis. The first was to calculate the school concentration index, a concentration index to measure institutional enrollment concentration around each zip code. The second was to calculate the average net price faced in each zip code.

We found that access has become more geographically unequal since 2008, with residents of poorer zip codes having much less access. Every year, millions of people are losing geographic access to higher education, which will no doubt have a significant effect on the student debt crisis.

Broadband access is a real issue accompanying geographic access, especially for students taking classes online, like so many are during this pandemic. Online instruction can’t be expected to mitigate geographic inequality because broadband access and geographic access are positively correlated. The HEROES Act does have 4 billion dollars allocated to increasing broadband connectivity, which is a positive step, especially for lower income students.

Our upcoming publication will focus primarily on financial access. We analyzed individual-level credit bureau data that breaks down student debt statistics by zip code. We’ll address how debt is specifically affected by various types of access issues, like with our school concentration index and average net price variables.

Marshall Steinbaum:

The diminution of state support since the Great Recession has fueled changes in higher education that are exacerbating the student debt crisis, including:

- The adoption of for-profit like business models by traditional institutions. Facing a lack of state support, institutions are searching for alternative sources of revenue and adopting strategies used by for-profits, such as expanding enrollment and offering additional nontraditional degree programs.

- Increasingly inegalitarian financial aid policies. Institutions are attempting to attract the students who are choosing from a large number of schools, and they do so by offering financial aid packages. These students, however, tend to be from more affluent backgrounds. Meanwhile, students from less affluent backgrounds take on more debt because the tuition that is charged to students of different financial backgrounds is becoming more inegalitarian.

Now, with the ongoing crisis, I see two major events that will likely lead to a worsening of the student debt crisis.

- The conduct of universities opening in light of the pandemic.

- The state budget austerity measures. More state budget shortfalls will exacerbate the funding crises that led institutions to seek out for-profit like business models.

It’s also likely that the credentialization dynamic will be further exacerbated. I did some research on this dynamic with Julie a few years ago. Essentially, the poor health of the labor market has led to the cost of obtaining necessary credentials for employment getting higher for workers. The cost of job training has slowly shifted from employers and institutions to workers and students.

Julie Margetta Morgan:

Our research often starts with thinking about the key assumptions around our student loan program, and the extent to which those assumptions are true. I want to talk about three core assumptions.

- It was assumed at the start of the student loan program that loans were for middle-income students. Government grants were supposed to cover costs for lower-income students.

- It was assumed that student loans would lead to more education and thus more earnings in the labor market.

- It was assumed that student loans were somehow race neutral, because they are offered to all students without any credit score or other criteria.

All three of those assumptions have been shown to be incorrect.

- Student debt is increasingly used to finance education for lower income students in addition to middle and higher income students.

- Since the Great Recession, we have seen a modest increase in levels of education but virtually no increase in earnings outcomes. The distribution of earnings largely stayed the same, despite the huge increase in student debt.

- Black borrowers fare far worse in the student loan program than their white counterparts. They borrow at higher rates, they borrow more, and they default at higher rates.

With regards to the effect of race on student debt, much of it can be tied to the underlying racial wealth gap, to Black students’ concentration in for-profit colleges, or to their need to attain graduate degrees to achieve the same earnings as their white counterparts. I think the missing piece is the effect of race on the type of servicing students get on their loans, as well as the way they’re treated by our debt collection systems. We’ve seen that race affects almost every part of the process, so although we don’t have the data yet, I would guess that race affects these points in the process as well.

In higher education, I don’t see an awareness of the lessons we should’ve learned from our last financial crisis. In 2007 and 2008, we didn’t provide enough sustained relief to state and local governments, leading to declining investment in public education and rising tuition and debt. Yet we seem to be headed in the same situation all over again. And the debt load that exploded between the last recession and this recession is still here.

Again, we need to be attuned to the role of race. We know that Black borrowers were already in the most precarious situations, and we also know that they are facing the highest rates of unemployment right now. We can expect that the outcomes will be even worse.

Dr. Jalil Bishop:

We need to start thinking about how we can have race conscious and anti-racist policies. We can’t limit the discussion to universal or class-based approaches and assume that they will include Black people. Many researchers and advocates use data from Black students to make the student debt crisis and their organizations hypervisible, but when it comes time to discuss anti-racist solutions, there’s a silence or neglect on the importance of explicitly discussing how we can protect Black students from racist systems.

We can’t allow data to drive the conversation without including Black voices and communities of color. Data plays a crucial role in understanding that there is a student debt crisis and specifically a Black student debt crisis, but it’s just one piece of the larger perspective. We have to start talking about what it means to actually address these racial inequalities. For me, that means expanding who’s usually included in this conversation, beyond the scholars and policy analysts. We need people who have the political will and capacity to bring debt cancellation to the forefront, and we need people who can do so in a way that centers an anti-racist perspective.

In my research, I’ve focused on capturing Black borrowers’ voices. By the end of this year, I will have interviewed somewhere between 150 to 200 Black borrowers, who are living with student loan debt during this pandemic and who were already experiencing student loan debt as a crisis.

I want to touch on three key themes from those interviews:

- Student debt is experienced as a lifetime sentence. Many Black borrowers tell me that they had no choice but to borrow in order to earn a degree and have some type of chance at earning a living wage. I hear that from borrowers who are making 40,000 dollars a year, and from borrowers who are making 6 figure incomes.

- The debt is generational. Many Black student borrowers’ parents also borrowed, and there’s a generational impact. Parents say that after borrowing for their oldest child, they’re not able to do so for younger children.

- Debt interlocks with other debt. If you need student loans, you probably don’t have a strong economic base to begin with. People explain that their student loan debt leads to more credit card debt or payday loans, leading to lower credit scores that come with another range of issues.

Legislative Proposals and Recommendations

Jen Mishory:

We need both policies that provide relief to struggling borrowers and policies that ensure that new debt accumulation does not accelerate. Broadly, we need solutions that address three goals.

- We need solutions that relieve the immediate financial distress caused by the pandemic.

- We need solutions that address the inequality being exacerbated by the pandemic. In the context of higher education finance, we need to pay attention to solutions that specifically address racial disparities in funding and debt.

- We need solutions that pave the way for a robust and equitable recovery.

I’m going to focus my time today on how to reduce future debt, and I think my co-panelists will spend more time on some of the debt relief provisions that have been discussed.

On the Context for Future Debt

A lot of the conversation has focused on ensuring that schools, particularly public institutions, can provide education without increasing tuition or cutting financial aid programs. The Center on Budget projects that states will face shortfalls of over 500 billion dollars through 2022. That’s just state funding; it doesn’t include the local budgets that are often key funding streams for community colleges. We’re already seeing some cuts happening, or we’re seeing states passing budgets and writing in cuts contingent on whether they receive new federal funding.

During the Great Recession, states slashed their budgets, and many never got back to pre-recession student funding levels. But, we also know that during an economic downturn, when opportunity costs are low, more students turn to colleges, particularly community colleges. A lot of the conversation right now has been about whether students will enroll this fall at the same numbers, but if we look back to the Great Recession, we saw that was a lagging effect towards the back end of the recession. Over the next couple of years, we may see a similar effect, where more people are turning to colleges.

On Potential Federal Policy Solutions

What does this look like in terms of policy solutions on the federal level? We need to see some of these investments at scale to states to support their public higher education institutions, from HBCUs to MSIs. This has looked a little different depending on the proposal:

- The HEROES Act in the House relies on direct to state funding, which provides a benefit by creating a state partnership where you can ask states to do more to ensure they’re not cutting funding.

- The Senate Democratic proposal relies on both direct to state funding and direct to institution funding. The proposal would create a significant pot of money that goes directly to states, and a bulk of money that goes directly to institutions. This proposal in particular is at a larger scale than most of the other proposals, as it would send about 132 billion dollars to higher education.

With all these proposals, the details matter. There are key questions around what you’re asking of states:

- Are you asking states to maintain funding and come back to the table as their economics get better?

- Are you making sure that when you say you can’t cut funding, you’re including state financial aid, for example, which wasn’t included in the state stimulus package in 2009? (The HEROES Act actually has a strong maintenance of effort.)

- Are you including an automatic stabilizer provision that says you’re going to keep up this support as poor economic conditions persist?

- Are you making sure that the Department of Education doesn’t try to inappropriately exclude certain students, such as undocumented students, from receiving money?

- When you send that money out the door, are you creating a formula to ensure that the institutions that are serving low-income students and students of color actually receive the funding they should?

Finally, I want to end on two important notes about the broader conversation on higher education in the pandemic.

- Everything has to be done within a conversation of accountability. We need to make sure that the predatory practices we saw increase during the Great Recession, such as for-profit colleges, are not proliferating or pocketing emergency stimulus dollars.

- Higher education should also pay attention to broader relief packages and efforts in response to Covid-19. For example, unemployment insurance reforms, like the new program in the CARES Act, can really impact students who otherwise can’t get state support. The Senate Republican proposal would actually roll that back and specifically exclude some of those students.

Laura Beamer: Ben, CAP has done a lot of work on the drawbacks of the higher education and debt relief proposals on the table right now, as well as about the CARES Act. Can you speak to the funding crisis and how relief funds should be distributed?

Ben Miller:

We need three things: debt relief, money for colleges, and money for states. If you only do one of those things, you’re going to undercut all the benefits you’d get.

- If we help borrowers but don’t do anything for states, the economy is still going to be in terrible shape. We may relieve some debt, but there won’t be any jobs to go back to.

- If we bail out colleges but don’t do anything for states, states will negate those efforts by cutting from their budgets however much we gave to colleges.

- If we just help states, we’ve seen in the past that they don’t always prioritize the needs of the institutions that serve the most borrowers, students of colors, and low-income students. We also wouldn’t be doing anything for borrowers.

With these three goals, it’s an “and,” not an “or.”

On Funding Allocation Under the CARES Act

The CARES Act made two really major choices. The first choice, you can understand. The second choice doesn’t make much sense, and it had some major implications.

The first choice was to allocate the funds based on “full time equivalent enrollment.” This adjusts a part-time student to be equivalent to only a fraction of a full-time student. In practice, it resulted in a substantial reduction in the potential funds that would go to community colleges: Community colleges educate around 35 to 40 percent of students, and they received around 27 percent of the dollars. As a contrast, public four-year colleges educate around 32 to 34 percent of students, and they received around 44 percent of the dollars. Private nonprofit schools were also substantially over-represented.

Going forward, we’re hoping to see fund allocation by headcount instead, treating all students as equal to one another. That would have a leveling effect, and be much more generous for community colleges. Part of what led to the massive spike in for-profit colleges after the Great Recession was that enrollment really grew at community colleges, but funding didn’t. Community colleges started to tap out in terms of their capacity and ability to enroll students in different programs. That really created a market opportunity that for-profits exploited very effectively. If you don’t fund community colleges, in addition to the bad effects it would have in increasing debt levels for students at greater risk, it would also help the for-profits.

The second choice was to treat all colleges equally within the formula, which meant that we sent direct institutional operating payments to for-profit colleges. I don’t think that’s defensible in any sense. The whole pitch on a for-profit college is that it can show its worth via its performance in the private sector. It doesn’t make sense that we spent about four percent of the four billion dollars for CARES on institutional support for for-profits. The good news is that it looks like for-profits will be more relegated in the future. HEROES takes them out entirely. The Murray bill puts them in a small set-aside. Mitch McConnell’s HEALS Act pushes them into a five percent set-aside that is available for all schools that are most affected. I think the notion that we’d give for-profits institutional support is highly questionable, especially when we’ve got the PPE program and other ways to invest in private businesses.

On Debt Cancellation Efforts

We unfortunately saw no real progression in the cancellation of debt in the CARES Act, and we unsurprisingly did not see any in the HEALS Act. We have seen calls for cancellation in both the bills from Murray, and from the House Democrats in the HEROES Act.

I want to highlight that Murray’s bills and the HEROES Act do their cancellation up-front, which is more equitable than cancellations along the way. People with low balances who are struggling, and either default before this started or are headed toward default, could get their whole balance wiped out right away, rather than having to wait for some point in the future.

There’s also no targeting done here. I think that was also a good move: even if you are predisposed to targeting, it’s really not a good idea to do it in current circumstances. We typically want to do targeting based on factors like income. However, we don’t know the income of most student loan borrowers, and we don’t know the income of any student loan borrower who’s not on income-driven repayment. Even for those who are on income-driven repayment, we know that their income as of when they last filed, which could be radically different from their current situation; you could have people who had a good income and subsequently lost their jobs. If we do means testing, they’re going to look like they’re in different circumstances than they really are.

Laura Beamer: At the Student Borrower Protection Center, Mike, you’ve done a lot of research working to curb predatory student loan companies and for-profit schools. Do you see any end in sight to these practices in proposed legislation? What issues arose with the CARES Act in particular?

Mike Pierce: It’s helpful to think about what the CARES Act does in the context of what it doesn’t do. More broadly, we can talk about it in the context of the gaps present in some of the initial relief proposals, including the CARES Act, the HEROES Act, and Senator Alexander’s proposal in the Senate.

On the CARES Act’s Universal Payment Pause

As a starting point, the CARES Act, with respect to student loan borrowers, is broad based. It did not make an attempt to target. It paused payments for all people with student loans owned by the federal government. That also means it left out about 9 million people with private student loans, or older federal loans that were made by banks and other private lenders, or by schools. But for everybody else—around 40 million people—student loans payments were paused, and they have been paused since March. It also suspended wage garnishment and other forced collections.

The universal payment pause has significant merit in this moment, because even on its best day, the student loan system is not dexterous. It’s not capable of seeing problems among student loan borrowers and responding quickly. It’s not even capable of seeing problems among borrowers and responding slowly. We’ve seen this with the failures of income-driven repayment, for example. So, opting into payment relief—which is what Senator Alexander proposes—is a very strange policy choice in a moment where there is broad financial distress among student loan borrowers.

On August 6, we saw some of the first household economic data from the Federal Reserve in New York. It showed that student loan borrowers’ distress has dropped by about half over the course of the past quarter. That’s the effect of solely the CARES Act pause on student loan payments. We’re also seeing a kind of inverse of what the CARES Act does among credit card issuers and mortgage servicers. People can contact their consumer finance company, and ask to pause their credit card or mortgage payments if they’re struggling financially. What we see in the economic data is that borrower distress, particularly in the credit card industry, has increased as the recession has ramped up and the pandemic taken hold. As a contrast, you have this universal payment pause under the CARES Act, and that’s resulted in fewer student loan borrowers under distress. That’s a really good piece of evidence to support continuing the CARES Act payment pause.

On Future Student Debt Cancellation

We also need to think about what comes after, when the recession starts to wane and we gain control over the pandemic. We’ve seen Congress, particularly Democrats in Congress, embrace different proposals to cancel debt. In the Senate Democrats’ proposal from March, they included $10,000 for debt cancellation for everybody. The HEROES Act included a targeted proposal to cancel student debt for economically distressed borrowers. There are some challenges around operationalizing that targeting, in addition to the challenges around the general idea of targeting student debt, particularly through an equity lens. But it’s good to see Congress thinking about broad based student debt cancellation.

Senator Alexander’s proposal does none of these things. The House proposal takes a step forward toward giving people some form of enduring debt relief. We have an opportunity here for an administration of either party to use the tools that it has under current law to cancel student debt for some people or for everybody. When you talk about the strain on the student loan system and its inability to respond to the crisis quickly, cancelling a modest amongst of student debt, even $10,000, will pull about a third of all student loan borrowers out of the system. That means the system will be better able to serve everyone else. You will not see some of the problems we see with income-driven repayment and other interventions if you just pull the most distressed borrowers out of the system completely.

Laura Beamer: The National Consumer Law Center’s Student Loan Borrower Assistance Project has done a lot of advocacy for student loan borrowers, before and during the pandemic. Persis, what are some of the vital protections that you and your colleagues are pushing for in the next Covid-19 relief package?

Persis Yu:

I want to start by saying that this crisis has exposed so many of the deep-rooted problems we have with the student loan system. It’s further exposed the racial disparities in the system. It’s exposed some of the most horrendous ways that we treat some of the most vulnerable student loan borrowers, particularly those who are in default. In normal times, the federal government hammers defaulted student loan borrowers. They seize borrowers’ wages and social security benefits without a court order. What this pandemic has finally exposed, although I think a lot of us already knew it, was that during a crisis, people need their money. They need to hold onto their money, and that helps them weather the crisis a lot better.

On Seizing Borrowers’ Wages and Tax Refunds

We released a report last month on the effect of taking borrowers’ earned income tax credits, where we found that borrowers who lost their EITCs experienced a lot of housing instability. They told us about how they struggled to feed their children, about how they struggled to even commute to work because they couldn’t fix their car. Having access to these funds is really critical, and it remains really critical. It’s important to note that low income folks have crises at times that are not during a national pandemic as well.

The CARES Act, like Mike mentioned, did cease some of these collection efforts, so that borrowers should not be having their wages or tax refunds taken if they have federal student loans. But that only started in March, which left many people in February without their tax refunds. Some of the research shows that people who most need their tax refund money file earliest, so this incidentally kept the money from the people who probably needed it the most.

These efforts have been bumpy. We’re now four months into the payment pause, and we’ve started talking about turning repayments back on. Yet, thousands of borrowers are actually still experiencing wage garnishment, because the student loan system is broken. It cannot turn off wage garnishment, despite the fact that Congress back in March directed the Secretary of Education to cease those collection efforts.

The borrowers that we hear from are terrified about the fact that collection is starting back up on October 1. Borrowers are going to start experiencing wage garnishment again. If they’re receiving Social Security, disability, retirement, etc., they’re going to start seeing those benefits seized from them. In addition to the other problems that Mike has talked about in the HEALS Act, the HEALS Act provides nothing for defaulted student loan borrowers. There was no relief for this group of borrowers, and many people don’t have any way to get out.

On a Two-Way Approach to Policy Solutions

We’ve been looking at this system with a two-way approach.

- We need to triage the system. For us, triage means that we have to extend the payment pause. And we have to extend it for all student loan borrowers, like Perkins borrowers and private student loan borrowers.

- We need to look towards recovery. As my colleagues explained, we need policies that will help borrowers recover, such as debt cancellation. But we also need to look more broadly at the way that the student loan system works. For example, we currently have no statute of limitations, which means that loans can follow borrowers for their entire lives, even if they’re in default. We need more long-term solutions, not just to get us over this hump, but to make sure that student loan borrowers, and the most vulnerable borrowers in default, are able to recover along with the rest of the country.

Laura Beamer: We’ve got a follow-up question from the audience. Some policy proposals are gaining bipartisan popularity on the Hill, including policies to expand Pell Grants, expand Public Student Loan Forgiveness, streamline IDR, and continue to suspend loan repayment fees. What should policymakers prioritize right now?

Persis Yu: First, we need a payment pause right now, and we need to make sure that pause is available to everybody. I don’t think there’s any way to get around that. We cannot turn collection back on on October 1.

Debt cancellation would be a really high impact way to get relief to a lot of folks, but we need to recognize that there will still be people who are struggling. We need to make sure that payment is easily available. We need to make sure servicers are doing their jobs. We need to make sure there is an easier ramp onto income driven repayment. We have called for letting borrowers who fall into delinquency be automatically enrolled in income driven repayment, so that people don’t fall into default just because they have failed to do some paperwork. Those are some of the ideas we have, and we have posted our priorities on our Student Borrower Assistance blog as well.

Laura Beamer: The costs of higher education passed down to students include the mismanagement of the funds, whether state or federal dollars. If there’s no true oversight on how the money is spent or wasted, how can we continue to fund in this way?

Ben Miller: Part of that is that there are certain institutions that we should not be funding as much or at all. Some of the waste is happening at for-profit colleges. Some of the mismanagement is a function of insufficient investment in public institutions. For example, if the University of Arizona had received sufficient long term investment, I think it would not have been interested in buying an awful institution like Ashford University. Likewise, some of the bad choices colleges are making in terms of reopening are functions of insufficient long term investment. They’re making choices that are not optimal for students in the long run so that they can secure their revenue for their bottom line.

If you were to invest more in these institutions, it would be important to pair funding with greater accountability, like Jen mentioned earlier. For example, increasing funding to states with conditions in place that say states have to maintain effort. Greater accountability is necessary so that students aren’t faced with impossible debt burdens and so that students receive the support they need.

I think the path to such a solution is actually to change the relationship between the federal government and higher education. We need to incorporate the states in meaningful discussion, and that is not happening currently.

Related

A First Look at Student Debt Cancellation

The first analysis of the policy-driven student debt cancellation that has been enacted over the last several years.

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt

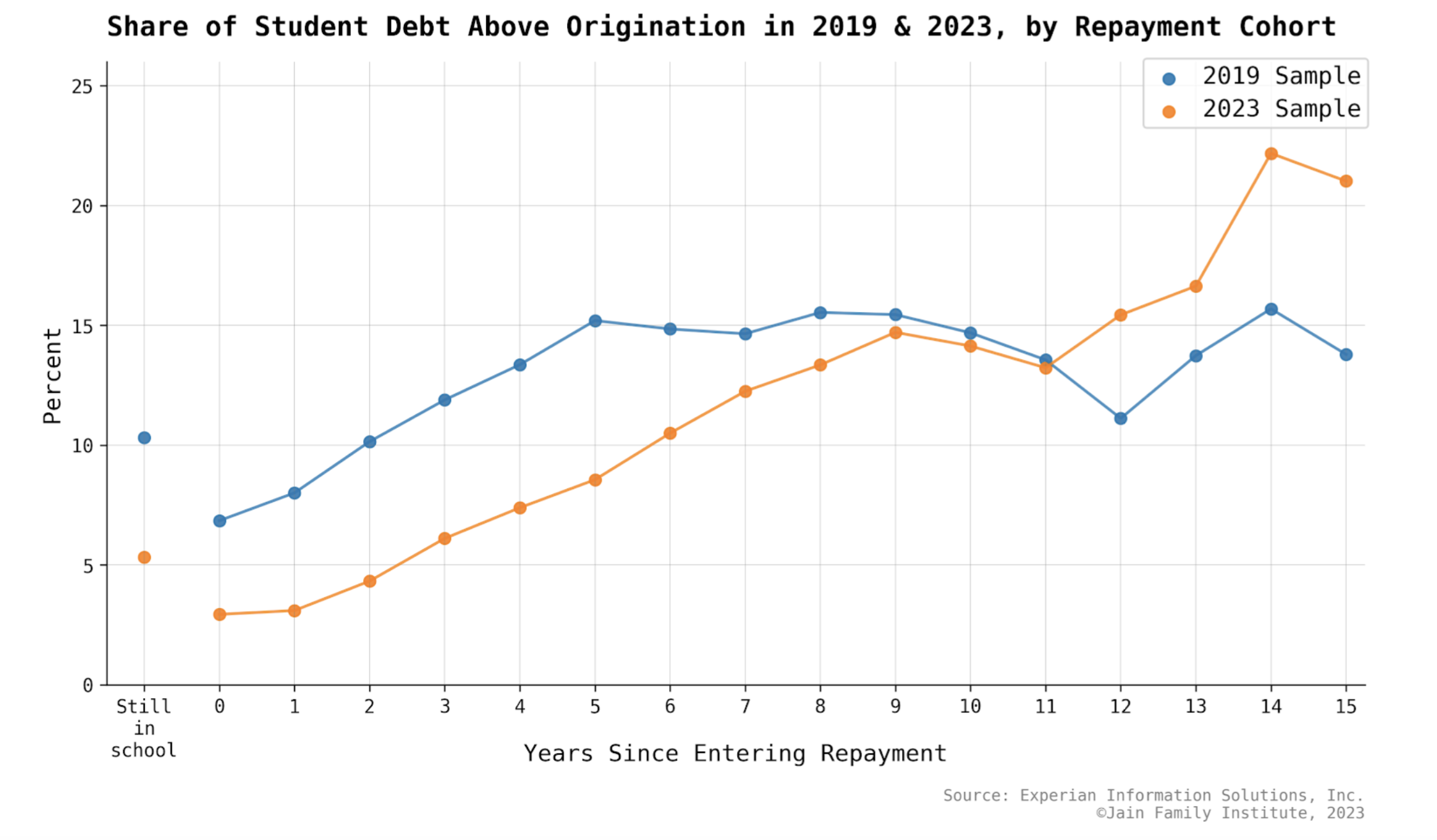

Student Debt Relief for Borrowers with Negative Amortization

The first installment of Part 14 in the Millennial Student Debt Series, this report analyzes systemic issues in student debt non-repayment...

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt

Student Debt and Homeownership Barriers in Washington, D.C.

Part 13 in the Millennial Student Debt Series, this collaborative report sheds light on the intertwined challenges of student loan debt...

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt