Policy Microsimulations

Revisiting the Child Tax Credit for the Lame Duck Session: Comparing Parameters for Anti-Poverty Impacts

By Halah Ahmad, Jack Landry and Stephen Nuñez

Download the full PDF here for best reading experience.

Summary

Child Tax Credit (CTC) reform may become a focus of the 2022 congressional, “lame duck” session as both Democratic and Republican proponents see the window for the legislation closing with a split legislature after the midterms. Advocates for the expanded CTC passed in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) hope the policy may pass through “tax extenders,” year-end extensions of expiring tax provisions often passed through consolidated appropriations, which can make an expiring policy permanent with various reforms, or renew it for additional years. While some Democratic legislators have signed a “dear colleague” letter opposing an extension of corporate research and development (R&D) tax credits without simultaneous tax cuts for children through the CTC, the specific scope of an extended CTC provision is unclear. In this brief, we review recent CTC proposals and simulate the effects of varying key parameters that may feature in lame-duck negotiations on a CTC tax extension. Sixty votes, including bipartisan support, would be necessary to pass a continuing resolution to extend any version of the CTC. The need for bipartisan support will likely resurface past contentions: whether the policy should be unconditional, with no minimum income requirement for all or part of the benefit; whether present benefit amounts should be increased; whether benefits should be unconditional to some children or households; and how quickly a benefit should phase in, if conditioned on income. All of these choices impact the poverty-fighting potential of the Child Tax Credit.

Contents

Below we examine policy parameters that most impact the CTC’s poverty-fighting potential across proposals to date:

- Faster income phase-in rates compared to unconditional benefits

- Full refundability for below school-age children

- Increased benefit amounts

Finally, we compare several policy options combining variations in the above parameters. An extension of the ARPA child tax credit represents the greatest anti-poverty impacts. Other options may achieve roughly a third to half of the poverty impact: modifying the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) CTC to introduce unconditionality for below-school-age children and a faster phase-in rate can decrease child poverty by up to 12 percent and deep child poverty by 22 percent.

We do not test every possible configuration of the above policy parameters. Instead, we provide analysis of proposals to date to approximate the impacts of varying each of these parameters. The ARPA CTC, with full refundability, no income phase-in, and a larger benefit amount per child, represents the policy with the greatest child poverty impact—an estimated 40 percent decrease in child poverty with full take-up(1). Among more limited proposals, we find that targeting younger children with an unconditional benefit (no income phase-in) is the best way to reduce overall child poverty due to higher costs and higher poverty rates faced by families with young children. Therefore, conservative proposals such as Senator Mitt Romney’s Family Security Act 2.0 and the existing TCJA CTC may dramatically increase their impact on child poverty if families with younger-aged children are excluded from an income phase-in.

More than any other parameter tested below, partial or full refundability at $0 in income (removing a phase-in entirely) contributes most to the policy’s poverty-fighting power, allowing poorest households to access the benefit. A benefit increase indexed to inflation does little to reduce child poverty without full refundability at $0 income for more households. More rapid phase-in up to $0.40-0.50 per dollar of income (along with a fully refundable benefit) can increase the policy’s expected poverty impacts compared to the TCJA baseline; above a 40 to 50 percent phase-in will not lift many more children out of poverty, though it may increase work incentives depending on assumptions about labor supply responsiveness, which we do not examine here. Unconditional, fully refundable benefits for households with below-school-age children could significantly reduce child poverty, up to 10 percent, if other parameters of the current TCJA CTC remain the same. Combined, a faster phase-in rate and unconditional benefits to young children can reduce child poverty by 12 percent.

We conclude by comparing the combined variations in these poverty-fighting parameters applied to the TCJA baseline: a faster phase-in, below-school-age unconditionality, and full refundability for an inflation-adjusted benefit—providing a picture of the 12 to 20 percent child poverty reduction possible with these changes, and comparative impacts by race and ethnicity for each reform. As legislators enter a lame-duck session and a politically split legislature in the next Congress, any of these proposals could inform a CTC tax extender or permanent policy next year.

Effect of Income Phase-ins and Conditionality

Full refundability results in the largest possible child poverty reduction, but a faster phase-in, up to 50 percent per dollar, can improve the poverty-fighting power of a conditional (means-tested) benefit. Above 50 percent, faster phase-in rates have limited impacts on overall child poverty.

The current Child Tax Credit phases in with income, meaning that as household earnings increase, they gain access to an increasing fraction of the benefit, determined by the phase-in rate per dollar of income. Approximately 25 percent of children (over 17 million) receive the CTC but get less than $2,000 because their parents have some income, yet not enough to get the full credit.(2) Modifying the CTC so it phases-in faster would increase benefits for this group of children.

Several components of the status-quo child tax credit contribute to its slow phase-in with earned income:

- The phase-in begins at $2,500 of earned income rather than $0.

- For every dollar of additional income, parents only receive 15 cents of the total child tax credit they can qualify for.

- The phase-in rate does not adjust for family size. Since families with more children qualify for a larger total CTC, to receive the full credit they need more earnings than families with fewer children.

- The refundable component of the credit is capped at $1,500; to receive the full $2,000, families must have tax liability. (3)

A number of reforms to the existing phase-in structure have been proposed for the child tax credit; advocates of an ARPA-like CTC favor getting rid of the phase-in altogether (rendering the benefit unconditional on income) and making the benefit fully refundable.(4) Some propose a new, faster phase-in rate that would be identical across households, meaning that households with different numbers of eligible children would receive their full CTC benefit at different points in the income distribution. Others, like Senator Romney’s FSA 2.0, instead propose phasing in up to a fixed level of earnings (in that case, $10,000) at which all families, regardless of household size, would have access to the full credit, meaning that households with different numbers of dependent children would experience different phase-in rates. Alternative proposals combine these ideas for a partial benefit at $0 in income with additional benefits conditioned on income. Figure 1 below compares the phase-in structures of several proposals to date, including the most recent expansion in benefit amounts with full refundability (ARPA, “Full Biden CTC Expansion” line), and the baseline Tax Cut and Jobs Act phase-in and benefit amount that will remain in place until 2025 unless another CTC provision is passed (“Pre-Expansion TCJA CTC” dotted line). The partial phase-in example provides half ($1000 per child) of the TCJA benefit at $0 income.

Figure 1

Example: A Faster Phase-in for the TCJA CTC

Figure 2 shows the child poverty effect of alternative ways of phasing in the TCJA CTC. The right-hand side panel modifies each component of the TCJA’s slow phase-in rate while preserving the basic structure. We start the phase-in at $0 of income (rather than $2,500), uncap the refundable portion so families can receive the full $2,000 in the form of a refund (rather than $1,500), and speed up the phase-in rate beyond the status-quo $0.15 per dollar of earnings (in five-cent increments).(5)

The right panel shows that with a phase-in between 40 and 50 cents, child poverty declines between 7 to 8 percent, roughly half of the poverty impact of an unconditional TCJA. At $0.40-0.50 per dollar, the anti-poverty effects of a faster phase-in start to plateau. Above this point, few families are affected by a faster phase-in—they either receive the full benefit or have no earnings and receive nothing. However, if a faster phase-in encourages more parents to enter the workforce by making the tax benefits from working more achievable, a faster phase-in above this level could further reduce child poverty.(6)

Figure 2

Another way to increase the phase-in rate is to set an income threshold at which the benefit fully phases in, and to standardize that threshold regardless of family size. This is the approach taken in the Romney Family Security Act 2.0 framework, and it represents a much faster phase-in compared to the TCJA baseline. This change is especially important for larger families, who need especially large levels of earnings to qualify for the full CTC. The anti-poverty effect of different income thresholds for receiving the full TCJA child tax credit is shown in the left hand side of Figure 2. Fully phasing in the benefit at $10,000 (the level set by FSA 2.0) would reduce child poverty by about 8 percent. Any threshold below about $35,000 would decrease child poverty, which illustrates how slowly the status-quo credit phases-in.

Other proposals to reform the TCJA’s child tax credit suggest proving half the benefit unconditionally at $0 income ($1,000 per child), coupled with a dollar-for-dollar (100 percent) phase-in (modeled in Figure 1). Partial unconditionality would have a greater impact on child poverty (12 percent reduction) primarily because the poorest households would receive some benefit (additional analysis available on request). In that vein, we discuss exclusions to the income phase-in in the next section; the more households exempted from an income requirement, the greater the anti-poverty effects of the program.

Full Refundability for Younger Children

Other than the ARPA CTC, providing a fully refundable benefit for households with young children is the best way to reduce overall child poverty. This is because families whose youngest children are below school age have higher costs of care and experience higher rates of poverty.

Parents with young children have more childcare responsibilities. Young children cannot be left unsupervised and are not yet eligible for public school.(7) Likewise, in households where the youngest child is below school age, incomes are typically lower (young parents). Previous research has similarly highlighted the higher poverty rates and extra needs of younger children.

Figure 3

Figure 3 corroborates this finding and illustrates the increased needs of families with young children, comparing poverty rates by a child’s age and poverty rates of households segmented by the age of their youngest child. The dark blue bars indicate that poverty rates for children between the ages of 0-1 are 2 percentage points higher than those of children aged 12-13 (poverty slightly increases for children above that threshold). However, there is an even steeper poverty gradient by the age of the youngest child in the household (represented by the light blue bars): 15.7 percent of families with a child aged 0-1 in their household are in poverty, compared to 11 percent of families where the youngest child is age 12-13, a 4.7 percentage point difference.(8) This illustrates how targeting entire families with young children better addresses inequities than targeting young children alone.

Example: Exempting young children from the TCJA income test

Figure 4

Whether for the TCJA or other conditional CTC proposals (e.g. FSA 2.0), targeting unconditional benefits to younger children—or to families with younger children—can increase the poverty-fighting power of an otherwise limited policy.(9) Figure 5 demonstrates the poverty and deep poverty impacts of an unconditional benefit to young children from age 0 to 5 (below school age).

Increasing Benefit Amounts

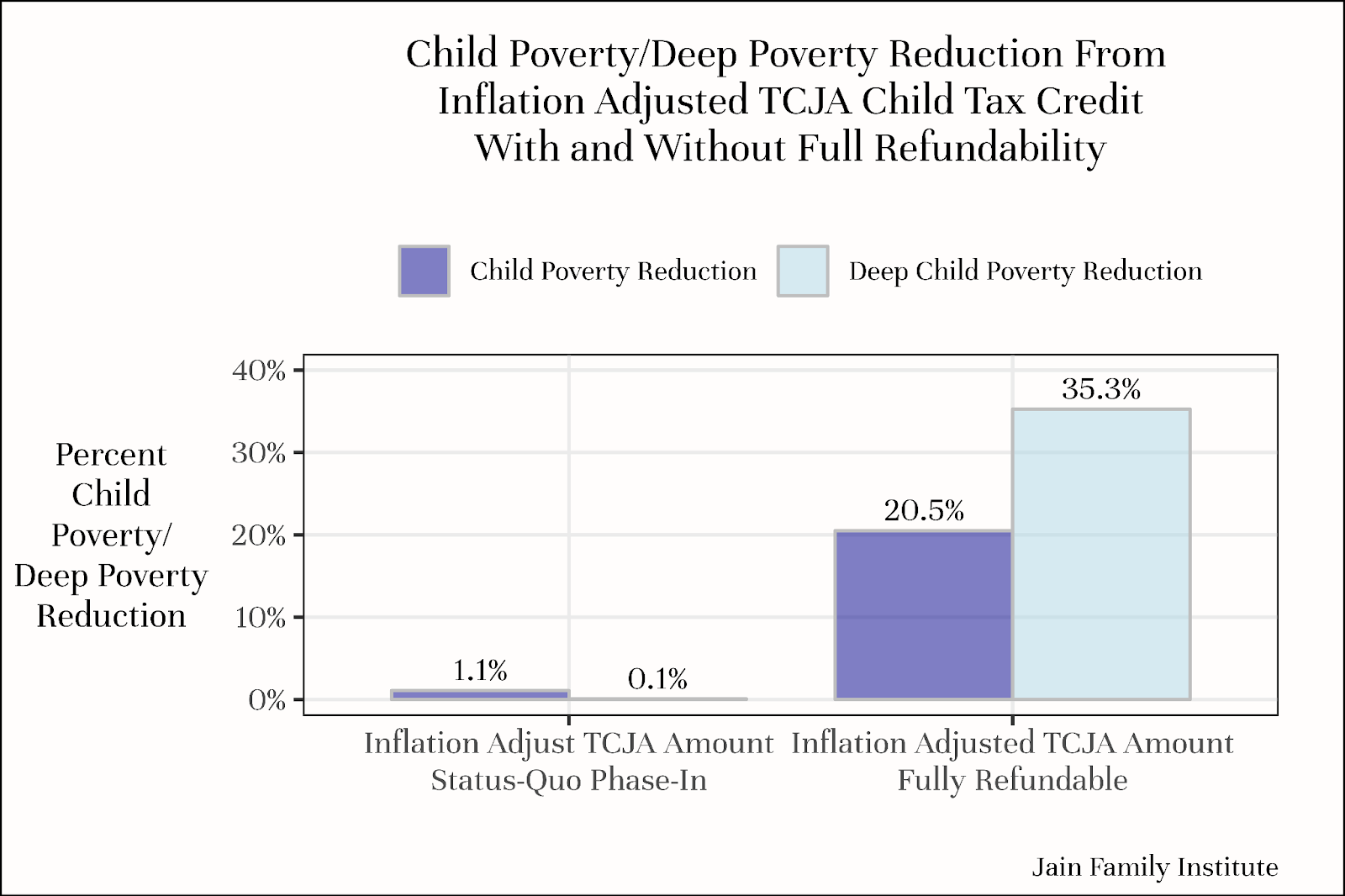

Larger benefit amounts are less effective at decreasing overall child poverty compared to full refundability and unconditionality for households with little to no income. A TCJA CTC adjusted for inflation does little to reduce poverty without full refundability for low-income children.

Figure 5

Amid rising prices due to both inflation and existing trends in the costs of raising children, many have emphasized the importance of increasing the child tax credit’s benefit amounts. The ARPA expansion included both an increase in benefit amounts and full refundability at $0 in income. However, in previous briefs, we have shown that increased benefit amounts have less of an impact on child poverty reduction compared to full refundability (at $0 income). Increased benefit amounts also come with significantly greater costs.(10) However, the existing, full child tax credit amount has not been adjusted for historic levels of inflation in the past year. An inflation adjustment to the TCJA CTC, which would bring the benefit from $2,000 to $2,300 per child, reduces poverty by only 1 percent without other changes to the TCJA phase-in structure. However, an inflation-adjusted TCJA benefit that is unconditional for all children can reduce child poverty by 20 percent, reflected in Figure 5.

Putting Poverty-Fighting Parameters Together

As we have argued in previous briefs, the best way to combat child poverty is to provide unconditional cash assistance. We could achieve a reduction in child poverty of roughly 15 percent by simply making the current $2,000/child benefit unconditional for all children (at a total cost of roughly $8 billion dollars/year).(11) Opposition to unconditionality from most Republicans and some Democrats means, however, that a fully unconditional benefit like the ARPA CTC is likely not possible in a bipartisan compromise bill. Therefore we have focused above on a range of reforms, including exemptions to the earnings requirement for households with young children, that leaves the basic structure of the TCJA CTC intact but meaningfully reduces child poverty (while potentially securing the votes necessary for passage). Below we combine these reforms to explore what a package of changes to the TCJA might look like, what impact it could have, and what it would cost.

Changes to the Tax Cut and Jobs Act to Reduce Poverty

There are any number of potential changes to the phase-in and earnings requirements that could be paired, so we have chosen to focus on examples of alternative CTC reforms that could both meaningfully reduce child poverty and serve as the basis for negotiations. We present two phase-in structures: a phase-in that starts at $0 income and fully phases in by $10,000 regardless of household size (the FSA 2.0 phase-in structure), and a fixed $0.50 per dollar phase-in structure. We chose $0.50 for the fixed phase-in rate approach because child poverty reduction begins to plateau at that point in a behaviorally-fixed microsimulation (see phase-in section above). It would be relatively cheap to phase-in more rapidly (e.g. dollar-for-dollar) but would do very little for the poverty rate.(12) For the exemptions from an income requirement, we focus on households that have at least one child under 6. As noted, if a fully unconditional benefit is not possible, there are good reasons to focus on creating exemptions for households with children below school age.

The “below school age” standard is the best of the potential compromise positions, especially if other, older children in the household receive the full benefit as well (acknowledging the childcare work of the parent filer). Exempting households with young children from an income phase-in can set a precedent for unconditionality and thereby set the stage for future reforms extending unconditionality to older children.

Phase-ins exclude or limit the benefit for the poorest households, create an administrative burden that can depress take-up (see next section), and make advance payments infeasible. Nevertheless, a more rapid phase-in does mean more households qualify for aid and this can have an important impact on child poverty.

Figure 6 compares changes to the phase-in, unconditionality for young children, and a combination of the two with a fully refundable benefit, our benchmark. The headline finding here is that pairing either phase-in structure with an unconditional benefit for all children in households with a child under 6 produces almost 80 percent of the poverty reduction associated with a fully unconditional benefit (a 12.3 reduction versus a 15.6 percent reduction).(13) This suggests there is space to generate a CTC alternative that would still meaningfully reduce child poverty.

Figure 6

Figure 7 presents the same information broken down by racial and ethnic group. In previous briefs we noted that an unconditional benefit particularly benefits Black households and that is clear here as well. An unconditional benefit for households including at least one child under the age of six would reduce Black child poverty by 15 percent. Including phase-in reform increases that to 18 percent (versus 23 percent for a fully unconditional benefit).

Figure 7

Comparing Changes to the Tax Cut and Jobs Act Child Tax Credit

Several proposals to date have suggested variations in the parameters discussed: phase-in structures, benefit amounts, and unconditionality for parents of below-school-age children. The table below compares the child poverty reduction of these combinations of CTC reforms. A summary of each of these proposals is also included in the appendix.

Applying the changes discussed above—faster phase-in rates, increased amounts, and age-based targeting—to existing law with the Tax Cut and Jobs Act CTC baseline, we see the trends remain consistent: the largest possible child poverty reduction comes from a fully refundable benefit that phases in at $0 in income.(15) The comparative costs are also stark: for $8 billion, almost 40% of the impact of an ARPA CTC may be achieved. Full refundability is the most cost-effective way to tackle child poverty.

We have also included a version of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s proposal for a CTC with partial (50 percent) full refundability and a 100 percent phase-in for the rest of the benefit, applying that notion to a TCJA-level benefit.(16) We have not included Senator Romney’s Family Security Act 2.0 framework because it makes other changes to the tax code in addition to a faster CTC phase-in and larger benefit amounts. However, we find that the FSA 2.0 would reduce child poverty by 11.6%; see the appendix for more on the FSA 2.0, and Figure 1 for a look at its basic phase-in structure.

Other Considerations: Phase-outs, Exemptions, Take-up & Administrative Burden

While we have focused particularly on phase-in structures, benefit amounts, and phase-in exemptions for young children, other parameters have sometimes been discussed that address the CTC’s fidelity to its purpose as a child wellbeing benefit and parents’ tax cut.

For example, even proponents of a conditional benefit may seek to exclude certain caregivers and types of income from a means test, such as grandparents, caregivers who suddenly lose their jobs and temporarily rely on unemployment insurance, caregivers who rely on Social Security Disability Income (SSDI), and caregivers who are work-limited while in educational programs. Just as an unconditional benefit can maximize the poverty impacts of the child tax credit, including these exemptions or additional types of income can increase the poverty-fighting power of a conditional program.(17) However, a reformed CTC that exempts certain groups from the earnings requirements could have broad eligibility but a dizzying array of rules. “All families are eligible, even if they didn’t earn income from a job” is a simple message that encourages families to claim benefits. “Some families without income from a job could still be eligible if you meet one of these exemptions” is more difficult to broadcast.

Take-up can be a major barrier to the policy’s success. To assess the effects of different child tax credit designs, we assume that all families who qualify for a given variation of the credit receive it. While this is standard practice, the takeup of tax benefits is, in reality, imperfect. In most cases, the overall anti-poverty effect of increasing tax benefits is somewhat overstated, but comparisons between different potential policies should be fairly accurate. When we test the effects of various child tax credits that carve-out certain families from an income requirement, this might not bear out in actual take-up. Normally, families with no earned income have no reason to file taxes—they would not receive any tax benefits or refund. During the pandemic, that changed, as families without income were eligible for three rounds of Economic Impact Payments and the expanded Child Tax Credit. The broad eligibility for these programs ensured publicity, both via news media and word of mouth. Second, simplified filing ensured families could receive benefits without onerous and confusing paperwork. Carving out specific groups from the earnings requirement would make both eligibility and the filing process more complicated. Carving out young children, while still vulnerable to this critique, is among the simplest possible carve-outs; it should have more limited take-up issues compared to more complex exclusions, preserving a strong anti-poverty impact.

Conclusions

Ultimately, across multiple parameters, a CTC that models off of the ARPA benefit will have the most dramatic impacts on poverty. But the second-best alternatives that cost significantly less are those that create an unconditional, fully refundable benefit for as many households as possible. Increased benefit amounts have smaller anti-poverty impacts than partially or fully unconditional benefits, but an inflation-adjusted CTC benefit may also be prudent. Several polls suggest that such reforms are popular, particularly as a necessary addition to any year-end package that extends tax breaks to corporations.

Download PDF version for full appendix.

Footnotes

- See previous microsimulations for more on ARPA CTC child poverty reduction estimates. This number does not account for inflation in 2022.

- These numbers come from a study using income data from 2017, so there are likely somewhat fewer children affected by the phase-in today.

- This number will be $1600 in 2023 with the existing inflation indexing of the refundability cap.

- Here, fully refundable refers to receiving the full benefit without any income. However, it can also mean lifting the refundability cap (point four in the list above), so families can receive the full benefit without having outstanding tax liability (In practice, making the phase-in slightly faster).

- Families can receive the status-quo CTC via earned income or tax liability. When modifying the phase-in, we only allow families to receive a partial CTC based on earnings. This will slightly understate the anti-poverty impacts of the phase-in if the tax liability path to receiving some CTC is preserved. We estimate that keeping the same phase-in rate ($0.15 per dollar), starting the phase-in at $0 and uncapping the refundable portion while preserving the tax liability path to receiving some CTC would reduce child poverty by about 1%.

- We are very skeptical of tax incentives’ effect on workforce participation. However, the tax incentive to work is a chief concern of Republican lawmakers. Since in most cases the status-quo CTC does not fully phase-in until past $30,000 of income, many low-wage parents working full time could not access the full credit, which limits its power as a work incentive. Making the credit phase-in faster could increase parents’ incentive to work and increase labor force participation. The Tax Foundation estimates that simply removing the refundability cap (which would only slightly increase the phase-in) would increase employment 4 times as much as marking the American Rescue plan permanent would decrease employment. To the extent employment dynamically responds to a faster phase-in, anti-poverty impacts would be even larger than what we estimate (which holds labor force participation fixed).

- Just 17 states mandate that school districts provide full-day kindergarten.

- These figures use the supplementary poverty line and data between 2018 and 2020.

- We ran a similar analysis of excluding young children or under-school-age children from an income test within the Romney FSA 2.0 child tax credit framework: unconditionality for children in households with at least one child under the age of 2 would reduce child poverty by 15.3 percent under the Romney FSA 2.0 framework, and 19.7 percent for unconditionality to households with below-school-age children (under 6). By comparison, the baseline poverty reduction of the Romney FSA 2.0 plan is 11.6 percent.

- Notably, increased benefit amounts to younger children—present in proposals from both parties—does increase the poverty-fighting power of the CTC marginally due to the higher costs and poverty rates among families with young children (see previous section). However, unless the benefit becomes unconditional for such children, only a small fraction of the increased benefit would reach the neediest such households, limiting its impact.

- The inflation-adjusted cost does increase the phase out thresholds to account for inflation. The version keeping the status-quo phase-in sets the refundability cap at $1,600 (what it would be in 2023 after adjusting for inflation) rather than $1,500 (what we use in the main analysis as the status-quo tax code in 2023.

- In a dynamic model where the phase-in generates an incentive to work, the poverty reduction (and cost) associated with a quicker phase-in rate could be more substantial. The literature is contentious and it is not at all clear how strong this effect is.

- We separately conducted analysis of the same changes to the phase-in structure paired with an unconditional benefit for households with children age 2 and under. That generates a reduction in child poverty of 10.5 percent.

- See appendix for further details.

- While previous debate has sometimes discussed varied phase-out rates, that aspect of the policy has little impact on the policy’s poverty-fighting power and only limited impacts on costs, so we have excluded it from this brief.

- The BPC plan is slightly different; they propose making slightly more than half the credit available at $0 earnings but phase-in the credit more slowly, among other changes.

- A long list of exemptions would necessitate a process to prove one’s eligibility, any of which would create barriers to filing many families would not overcome. Some exceptions to the normal earnings requirement, like the age of a child or parent claiming them, would be simple to verify without additional documentation. (One thing the SSA has good information on is peoples’ ages). However, other proposed modifications would be more difficult.